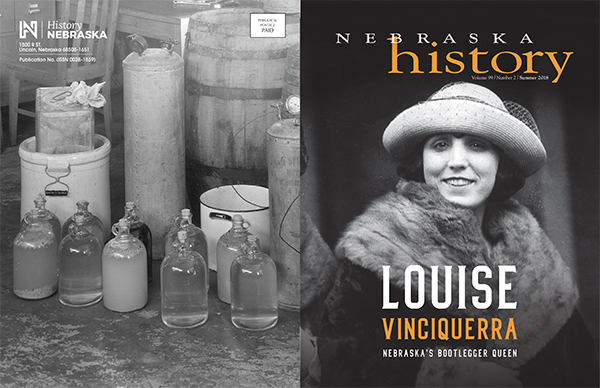

Law enforcement seized this still and jugs of moonshine from a Lincoln basement in 1931. We wanted to know more about it, so we asked Nebraska author and folklorist Roger Welsch. He has studied the art of distilling (purely for scientific purposes, you understand!) and knows experts in the field. Below, he tells us more about the equipment we see here.

A detail of this photo appears on the back cover of Nebraska History (Summer 2018), to be published in mid-May:

The issue includes “Louise Vinciquerra, Nebraska’s Bootlegger Queen,” by Kylie Kinley. If “Queen Louise” were still around, she could tell us how she and her associates manufactured liquor during Prohibition. Instead, Roger and his friends looked closely at this photo and offer some insights:

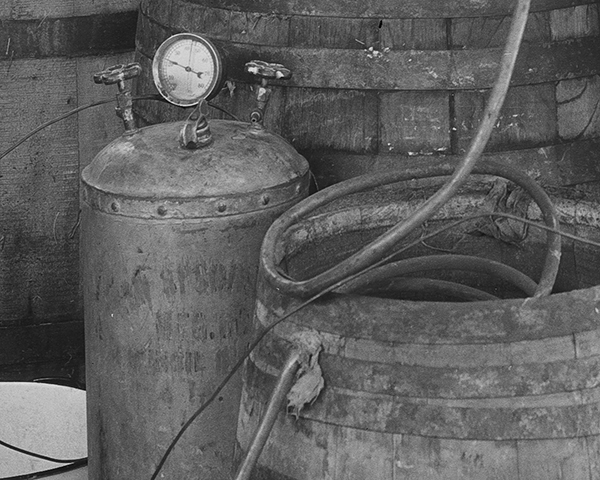

“On the most basic level,” Welsch says, “the round metal ‘barrel,’ front center with the ‘pipe’ coming out the top, is a copper pot still. It is sitting on a burner. The copper pipe coming out the top runs into a coil in the condensing barrel. ‘Mash’ (sugar or anything starch—grain, potatoes—that can be converted to sugar) is fermented in the open top barrels.”

“After the sugars have been converted to alcohol by yeast, the mash is put in the copper pot and heated. The alcohol boils off, runs out the top tube and into the condenser, barrel…the one with the copper coil in it. The coil in the barrel is bathed in cool water and the alcohol vapor condenses, goes out of suspension, just as beads of water condense on a cold glass, and exits the tube as moonshine.”

As for the jugs themselves, some contain clear liquid, some cloudy. In an earlier conversation, Roger had suggested that the cloudy jugs might contain “tails,” the last that comes out of the run, “high in flavor, lower in alcohol, destined to go into the next batch for a rerun.”

But Roger was curious about the floaters and sinkers in some of the cloudy jugs. “Oyster shell to raise pH? Yeast culture?” It was a mystery until he zoomed in and found…

…Maggots! Eww!

“Talk about giving a bad name to the science! If those are indeed tails, then it was low enough proof for flies to get into it. I’m thinking the law didn’t take as good care of these items as the operators probably did.”

The experts agree it looks like a well-made still. “The tall, thin cannisters with pressure gauges probably contain fuel (pressurized white gas?) for the burner, which can be seen under the still. Like working with a hair-trigger bomb!”

As for the clear jugs, one of Roger’s friends guesses that they contain the “hearts” of one run of the still. Roger explains that this is “maybe six gallons of 120-140 proof ‘white dog’ or raw whiskey, ‘proofing out’ to maybe 9 gallons of 90 proof moonshine. That would be about right for this size still. With the number of open end barrel fermenters I see here… maybe 10 or 12?… they could easily do a run a day in that still (40 gallons maybe?), some days two, depending on how fast their mash was fermenting. And that could depend on a lot of things, especially temperature.”

“That’s a lot of ’shine! Four to or six cases a day… Yikes! A dollar a pint? My Dad was making two dollars a day shoveling coal into the University powerhouse. A lot of hot, dirty, hard work but a good living wage. I mean making whiskey, NOT shoveling coal!”

These days, making liquor is again providing a living wage to Nebraskans as small, locally-owned (and legal) distilleries have opened in parts of the state—including in St. Paul in Roger Welsch’s own Howard County. We suspect it’s a lot easier to make a high-quality product when you don’t have to hide the still in your basement or out on the back forty.

—David L. Bristow, Editor