It was Lincoln’s most sensational criminal trial of the nineteenth century. But as historian Timothy Mahoney argues, the Sheedy case was more than just a sordid tale of murder, adultery, and greed. In “The Great Sheedy Murder Trial and the Booster Ethos of the Gilded Age in Lincoln” (Nebraska History 82, Winter 2001) he uses the case as window into the culture of the times. More recently, Mahoney and a project team from the University of Nebraska at Lincoln have created a website called Gilded Age Plains City: The Great Sheedy Murder Trial and the Booster Ethos of Lincoln, Nebraska, which has lots of other background information on nineteenth century Lincoln. (Word of warning: the site is fascinating, but its non-linear structure can be confusing if you’re not already familiar with the Sheedy story. Read the article first. It’s also available—with links to news clippings—at the Gilded Age Plains City site by clicking the “Interpretation and Narrative” button.) A few excerpts:

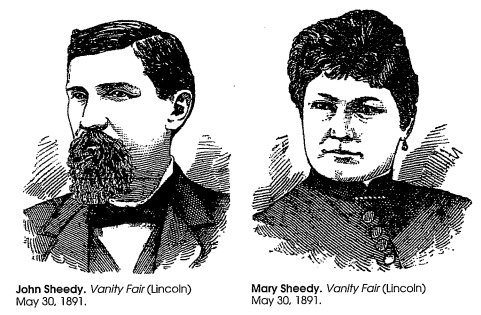

Just before eight o’clock on Sunday evening, January 11, 1891, John Sheedy, a Lincoln, Nebraska, real estate developer, hotel owner, noted “booster,” and “sporting man” stepped out the front door of his house on the southeast comer of Twelfth and P streets to go two blocks over to his gambling establishment in the “uptown” district. Suddenly, out of the shadows, a man charged toward him, striking him on the side of the head with a leather-covered steel cane. Staggering, Sheedy drew a pistol and fired several shots, but missed his assailant, who disappeared down Twelfth Street into the dark. Sheedy’s wife rushed from the house to help her husband back into the parlor, then called for a doctor and the police, as neighbors, including another doctor, gathered. Doctor C. S. Hart and the chief of police, Marshal Samuel Melick, soon arrived, and as the two doctors dressed Sheedy’s head wound and helped him to bed, Melick questioned him about the attacker. The doctors administered pain relievers, and Mary Sheedy gave her husband sleeping powders in a cup of coffee. In the middle of the night Sheedy was stricken with paralysis. He fell into a coma the next morning, and the doctors ruled out surgery. He died about ten o’clock Monday night, twenty-six hours after the attack.

Police soon arrested a man named William “Monday” McFarland, who confessed to the crime, allegedly after the police threatened to turn him over to a waiting mob (McFarland was black, and lynching was a real possibility.) McFarland said he had been coerced into the murder by Mary Sheedy, who after the attack had finished off her husband by poisoning his coffee. When an autopsy confirmed the presence of poison, Mary Sheedy was arrested and, like McFarland, was charged with murder. As the alleged facts of the case, established by McFarland’s confession and supported by testimony at the coroner’s inquest, became public, Lincoln society was thrown into a frenzy.

Why did the case strike a response strong enough to trigger a general crisis of confidence? First, the murder itself shocked Lincoln and raised fears that crime was on the rise. Having managed to avoid the disorder, crime, and violence so common across the urban frontier, Lincoln had established a reputation as an orderly city. Indeed, since its founding in 1867, there had been few murders, and only one Lincoln man had been executed. Second, the identity of the alleged assailants and McFarland’s lurid confession sent waves of concern and panic through Lincoln’s middle class, and Mary Sheedy’s story raised profound worries about the integrity of the class, gender, and racial systems that had sustained Lincoln society for a generation.

For years, John and Mary Sheedy had been moving on the edges of Lincoln’s genteel society. Although a known gambler, John was praised for his civic-mindedness in downtown development, his active interest in the affairs of the booster ethos, his liberality to local charities and institutions, and his magnanimity toward “friends” among the city’s elite. Mary patronized genteel stores, established a genteel house, and made a foray or two into Lincoln’s middle class social circles. The possibility that she had hidden two previous marriages and possibly had committed adultery, miscegenation, conspiracy, extortion, and murder was a shocking breach of middle class decorum, and raised deep fears that other “poseurs” and “charlatans” might be living among them. Such corruption undermined the middle class sense of order and called into question its image of itself as having been built on strong moral character cultivated through self-discipline, hard work, marriage, genteel living, and civic involvement. It also eroded the middle class’s confidence that it could police itself and maintain a moral social order.

The case itself grew more complicated. There were a lot of people in Lincoln who had reasons to want John Sheedy out of the way. But as for the results of the trial… you’ll just have to read the full article (PDF). —David Bristow, Associate Director for Research and Publications

(Posted April 23, 2010)