By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

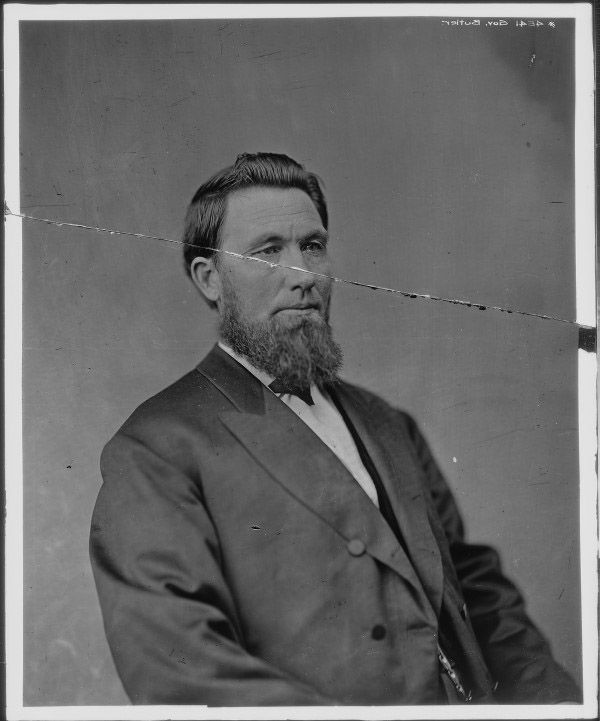

Throughout Nebraska’s history, many figures were credited for shaping the state. Often they are recognized most for their positive influence, but this was not the case for Nebraska’s first governor. David Butler, elected in 1867, served two terms before getting impeached, convicted, and removed from office as a result of fraudulent financial matters. While the public praised him for his accomplishments in office, there were hushed secrets behind his success.

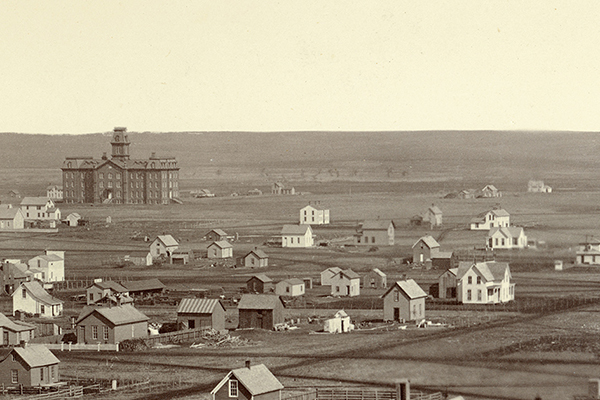

In 1867, the state’s capital was relocated from Omaha to Lincoln, and stakes were high for Butler to establish Lincoln as the capital city. Between political party conflicts, the need for a capitol building for legislative sessions, and the goal to establish Lincoln, Butler made haste. Before long, public buildings appeared—such as the capitol building and state university—and what had been a little town in Lancaster County began to grow into a prospering city.

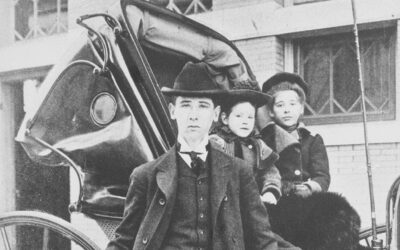

David Butler was born December 15th, 1829 and died May 25th, 1891. Image Source: Wikipedia.

At the time, members of the legislature were aware that Butler ‘pulled strings’ in order to construct Lincoln in a such a short time, but considering his success, many overlooked the issue. The governor used this to his advantage and continued to make problematic decisions. While others turned a blind eye, his political opponents were not as quick to condone his behavior, and though they wanted him out of office, there wasn’t enough evidence to enact a conviction or impeachment.

That was until 1871, after Butler was elected for a third term.

In January of 1871, during a legislative session, Edward Rosewater (an Omaha Republican and publisher for the Omaha Bee) asked Butler to account for the school land funds collected from the federal government. It was noted that there was a certificate of deposit for the fund that Governor Butler signed, but there was no legitimate record of the deposit itself.

Concerned, the legislature began questioning the whereabouts of other funds and it was agreed that an investigation was necessary. However, it wasn’t long after the investigation started, that they realized the rabbit hole they fell into.

The first capitol building in Lincoln (image: circa 1868) was built so poorly that it needed repairs within its first few years. Lincoln’s current capitol building sits on the original building site.

It was discovered that after the relocation of the capital, Butler entered questionable contracts for the construction of a number of Lincoln’s public buildings. The capitol building was one of the most costly. Not only did its contract exceed the set appropriation, but it was twice the amount. During that period Butler also accepted bribes from railroads, “private individuals,” and political figures (some of whom he loaned state money to).

The University’s lone building as seen from the tower of the state capitol, Lincoln, 1872. The first university was described as “drafty” and “was so poorly built that its roof leaked and its foundation began to crumble.

Newspapers began sparking public outcry.

Initially, Butler dismissed it all as “rumors” and “gossip,” but eventually he admitted that in certain instances he “exceeded instructions,” but argued that it was in the best interest of the state.

Butler justified his loans by explaining that “bonds [were] depreciating rapidly” and the individuals he lent money to were, “better security.” When asked specifically about the federal school fund, he confessed that he used it for personal endeavors, but that it was “adequately secured by the Pawnee County Land mortgages.”

The school fund, however, was worth approximately $17,000, whereas the value of the Pawnee County Land mortgages was only valued at about $8,000. It was also reported that the mortgages had been written out since May of 1869, but weren’t recorded in official books until 1871 (the year of the investigation). There was also another fund that was valued at about $16,800 and had no deposit record.

These discoveries led people to question the credibility of Butler’s associates: former secretary Thomas Kennard and auditor John Gillespie. There were rumors that Gillespie took money out of the state treasury with the intent to put it towards landscaping around the capitol when instead he distributed it between himself, Kennard, and Butler. This was never confirmed though.

When investigating the record books, it wasn’t clear that any state funds even existed in the bank. Not only were state and private accounts not separated, but they were unidentifiable. According to one source, state funds were also logged under the name of “John Rix.”

As evidence accumulated and the impeachment trials began, the public shared varying opinions.

One reporter wrote that any man who voted to “acquit Governor Butler in the face of testimony,” would “never be heard of in Nebraska, or anywhere else for that matter, in a position of public trust.” Another writer defended Butler by stating that “gratitude is the worst vice of human nature,” and that the state was “ungrateful” and “ungenerous.” Continuing to justify Butler’s actions: “In appropriating money at his disposal, he [David Butler] would have done no more than is done in every business firm in the country – men appropriating receipts and leaving a memo of the fact in the safe.”

Regardless of the public’s opinion, David Butler was convicted and removed from office. There were eleven articles, each one voted on separately, but Butler was only convicted of the first: the mishandling of the school land funds. In response to his impeachment, one article discussed Butler and his political career being “dead,” according to the public. The writer disagreed and said that the court “let him escape without killing him,” that Butler couldn’t be “killed” and wouldn’t stay “dead.”

David Butler returned to his Pawnee County Farm where he raised stock. In 1877, his impeachment proceedings were removed from his record and he did make an eventual return to politics. He was elected into the state senate in 1882 and attempted to run for governor one last time in 1888. Despite his attempts, Butler’s reputation would be forever tainted.

While David Butler’s time in office involved financial corruption, it encouraged people to be more cautious, hold political figures accountable, and in the end, helped to shape the Nebraska we know today.

Sources:

John J. Montag, R. C. Naugle, J. C. Olson (2014) History of Nebraska (4th ed.) University of Nebraska Press

Dakota City Mail – February 17, 1871

Nebraska Advertiser – March 16, 1871

Nebraska Chronicle – February 11, 1871

Nehama Valley Journal – March 16, 1871

The Nebraska State Journal – January 11, 1871

The Platte Journal – February 1, 1871

The Platte Journal – June 21, 1871

(First Posted Feb. 12, 2021)