When A. N. Ward reminisced about his early hunting exploits with a reporter from the Omaha World-Herald in 1910, he recalled the days when the Nebraska prairie abounded with wild game. Ward, according to census records, was seventy years of age and had lived in the vicinities of first Arapahoe, and then Milford, for nearly half a century. The Sunday World-Herald’s account of his hunting yarns, published on October 2, 1910, noted: “In recounting some of his experiences of the early days in the state, Mr. Ward said that he was thoroughly convinced that he killed the last wild buffalo killed in Nebraska. ‘With Dan Prime and John Russell,’ he remarked, ‘I was up at the head of the Birdwood river, in McPherson county, hunting blacktail deer. In October 1881, and on coming into camp down the valley, the second day we were out, I saw this buffalo, which proved to be a two-year-old heifer, coming out of the shallows where it had been for water. I made a capital shot, killing the heifer stone dead at 160 yards, with a bullet back of the left fore-shoulder. That was the last buffalo killed in the state, or at least the last one of which I could get any authentic account. In fact, I never heard of one being killed later, but was told that a herd of six or seven were seen later that month up on the Dismal.'”

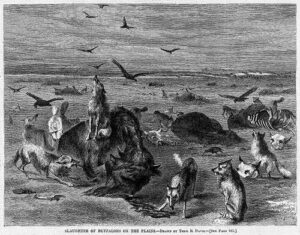

This illustration of slaughtered buffalo on the Plains appeared in Harper’s Weekly, February 24, 1872.

Ward also recalled his success in hunting antelope. “‘Again the fall of 1883 found me camped on the east fork of the Birdwood, and one day while trailing a wounded deer, I discovered a band of twenty-five or thirty antelope approaching me from across the prairie. I was shooting a new 40-82 Winchester that fall . . . and when I saw these antelope I dropped in the grass and waited for them. I knew that [they] had seen me disappear, and knew that their curiosity would bring them up close to my hiding place. In fifteen minutes there they were, all lined up in front of me like soldiers on dress parade, not 30 yards away. What did I do? Well, I am ashamed to make the confession in these days of the true appreciation of our wild creatures, but I jumped to my feet and began pumping it into them, and before their fleet limbs could carry them out of range, I had seven down!'” Perhaps realizing the effect these stories might have on newspaper readers in 1910, Ward said, “‘Now don’t think for a moment that I am glorying in these extraordinary killings, for I am not, and while I regret it now, console myself with the realization that they were made in a day and an age when an entirely different sentiment prevailed as to the ethics of sportsmanship, a day and age when it wasn’t even dreamed that the deer and antelope ever could be killed off and driven away. The killing of seven antelope occasioned no more surprise then than the killing of seven grasshoppers would have occasioned.'” Ward also recalled the disappearance of game during the early 1880s: “‘As near as I can fix it in my mind now the blacktail deer all disappeared from the country in the summer of ’85, and the bulk of the antelope followed in ’87. The blacktails got so wary that it was impossible to get within gun shot of them. They were even quicker witted than the gray wolves, and in ’83 we got but two deer the whole fall. The flushing of a bunch of grouse was the signal for every deer within a radius of miles to get up and go, and we got to thinking that the birds and the deer understood each other too but I suppose that was only fancy.'”