By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

In a period of intense racial discrimination, groups like the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) formed to provide support and a voice for African Americans. As oppression increased, branches were established in Omaha and Lincoln. Zachary Wimmer highlights some of the prominent events, activities, and members in “Triumphs and Troubles: The Early History of the NAACP in Nebraska, 1918-1940”: a featured article in Nebraska History Magazine’s Winter 2020 issue.

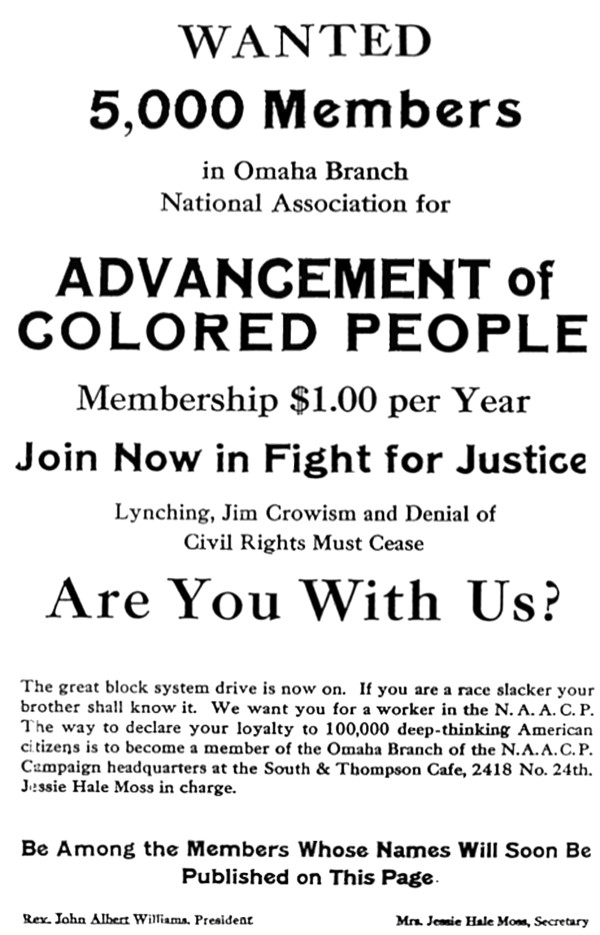

Omaha was the second city (behind Lincoln) to establish a NAACP branch in Nebraska. It began in 1918 with 52 members and grew to 800 member. The branch often served as a resource in cases involving racial profiling and hate crime.

In 1922, three years after the Lincoln branch addressed the issue, Omaha’s NAACP confronted Moon Theatre for showing “The Birth of a Nation,” a 1915 film presenting the Black community in a negative light while portraying the Ku Klux Klan as honorable. The theater agreed not to show portions of the movie that glorified the Klan. This was one of the branch’s first victories.

Terror shook North Platte in 1929, after a Black man killed a police officer and later died while resisting arrest. Following this, White community members went to the homes of Black residents and ordered them to leave town. Fearing violence, Black residents fled.

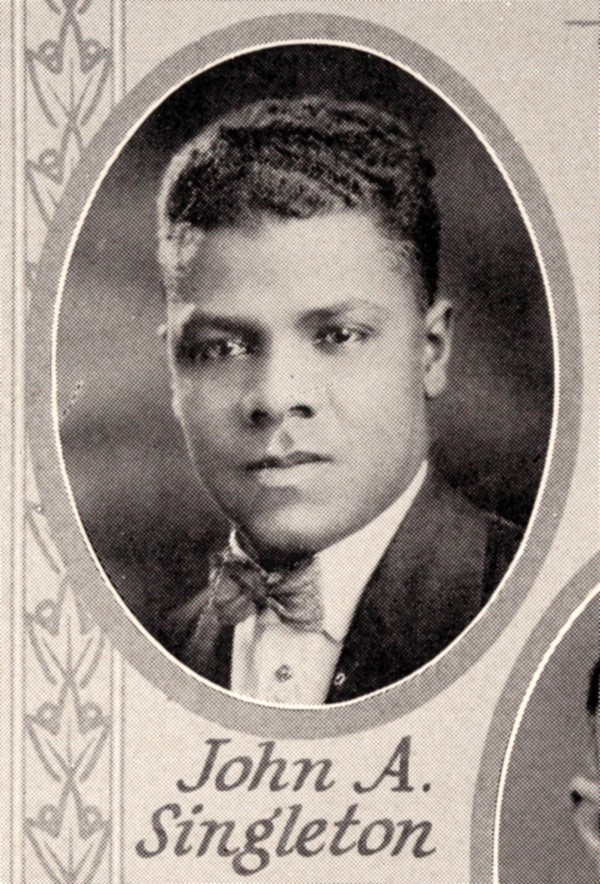

John A. Singleton, NAACP-Omaha’s president, led a committee demanding Governor Arthur Weaver to protect the fleeing residents. An NAACP official traveled to North Platte to gather evidence. Black residents soon returned to their homes, but a local jury refused to convict the men who made the threats.

During the Great Depression, many NAACP branches ran short of funds. The Lincoln branch went bankrupt and lost its charter in 1939 after becoming inactive in 1935. The Omaha branch survived, but its membership shrank from more than 800 members to only 350 by April 1933.

In 1931, the dining room at Omaha’s Brandeis department store began refusing to serve Black customers during peak hours. Singleton warned the store that the NAACP would not condone the matter. Nebraska Attorney General C.A. Sorenson warned Brandeis that Nebraska law gave “colored people the right to a ‘full and equal enjoyment’” of all services. The store backed down and the success was noted as “a tangible gain of racial progress in the state.”

While NAACP efforts proved successful in many cases, some were not as fruitful. Lottie Dixon, for example, was a Black woman killed during arrest by Officer Harry Green, who said that his gun had misfired. The Omaha NAACP protested, but days later Dixon’s death was ruled an accident. Two White examiners validated Green’s statement that Dixon had been shot while reaching for the officer’s gun, but a Black medical examiner argud that “if the shot had been fired at close range the powder would have made a tattoo on the skin.” There was no such marking. The court disregarded his statement. The officer was released from custody and returned to duty.

While the branches and the national organization shared most successes and failures, certain incidents divided them. In November of 1928 a couple was brutally murdered in their Carter Lake home, the fourth and fifth murder victims in that area over a three-day period. A Black man named Jack Bird was convicted and sent to the state penitentiary. H. J. Pinkett, a member of NAACP-Omaha, was adamant that Bird was innocent. Pinkett reached out to the national headquarters, but was denied support because they didn’t view Bird’s arrest as an act of racial profiling. Pinkett continued to fight unsuccessfully for Bird’s exoneration; twenty-one years later, Bird confessed to this and other murders and was executed in 1949.

The Omaha branch of the NAACP remains active to this day. Wimmer’s article covers the period before the Civil Rights Movement, when the NAACP laid the foundation for later efforts by the NAACP and other civil rights group.

Read more about Nebraska civil rights history.

Photos:

Top: “NAACP recruitment flyer, 1918.”

Bottom (left to right):

(1) “John A. Singleton served as president of the Omaha NAACP 1928-1933, and was a member of the Nerbaska legislature’s House of Representatives 1927-1928, Nebraska Blue Book 1927.”

(2) “In 1931, Omaha’s largest department store began barring Black customers from its dining rooms during peak hours. The Omaha NAACP convinced the state attorney general that the practice was illegal. November 1938 photo by John Vachon. Library of Congress.”

(12-3-2020)

The entire article can be found in the Winter 2020 edition of the Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues per year.

Categories:

NAACP, Civil Rights, Omaha, Lincoln