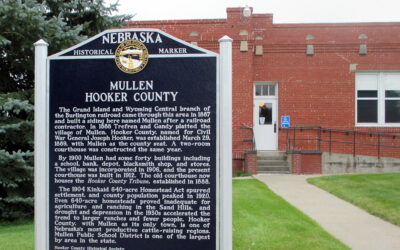

In honor of Nebraska’s historical markers, the History Nebraska blog is instituting Marker Mondays. Each Monday, we will feature one of our state’s historical markers, providing information on its text, location, and reason for its placement. But first… Where did all these markers come from, anyway? Former History Nebraska Senior Research Historian James E. Potter filled us in.

Many Nebraskans are probably familiar with the blue and silver historical markers (of various styles) that stand along highways, on courthouse lawns, in front of historic buildings, and at many other locations across the state. After all, there are now more than five hundred of them. No such markers could be found anywhere in Nebraska before 1961, when the first one was dedicated in the town of Fort Calhoun on May 21, 1961. That marker told the story of Fort Atkinson, the important U.S. military post that once stood nearby along the Missouri River from 1821 to 1827.

Of course historical markers had been erected in Nebraska well before 1961, but they resulted from local initiatives, or in the case of the granite Oregon Trail markers installed in 1912-14, from collaboration by the Nebraska State Historical Society and the Daughters of the American Revolution. Not until 1957 did the state legislature decide that marking Nebraska’s historic sites was too important to leave to happenstance. The bill that passed that year gave that responsibility to a historic sites council of three state officials, but lack of funding and the members’ other duties precluded much activity. In 1959, at the urging of History Nebraska, the 1957 law was amended to create the Historical Landmark Council with five members appointed by the governor, plus the governor himself, the History Nebraska director, and the state engineer. The council would approve each marker and encourage local sponsorship to provide half of the $350 cost of the largest marker.

The Department of Roads would install markers proposed to go along state highways. And that’s when the state historical marker program really began to flourish. The Landmark Council approved standard designs for historical markers (designs still used today), contracted with a marker foundry, and began selecting significant Nebraska sites that would receive first priority for a marker. These included Fort Atkinson, Chimney Rock (the second marker installed), Ogallala as “cowboy capital,” the Mormon Trail, and the Homestead Movement. By 1963 the council had contracted for fourteen markers and nine had been erected. The program accelerated during the state centennial in 1967 with nearly eighty markers in place by year’s end. Although the appointed members of the Landmark Council were well qualified to evaluate marker proposals, it became difficult to arrange the necessary meetings to keep the program running efficiently. Because History Nebraska already handed the financial and administrative aspects of the marker program, and its staff researched and wrote many of the texts, the legislature in 1969 decided to make the History Nebraska responsible for the state marker program, an assignment it continues to perform.