We’ve learned the doorman’s name and his family’s story. William Patrick was the son of an enslaved man, and his parents were the first Black farmers in Hamilton County. Now we can tell the personal side of the story.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

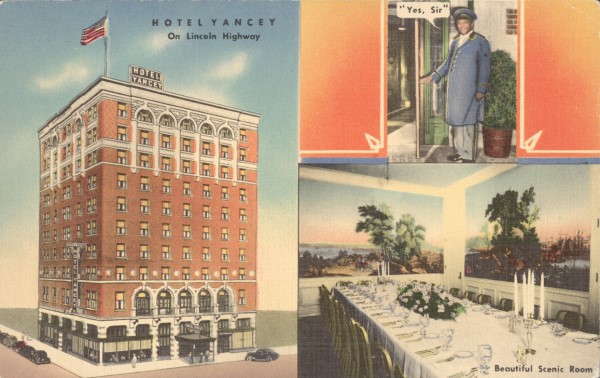

Shortly after I posted the above photo and wrote about the racial history behind it, I heard from the Plainsman Museum in Aurora, Nebraska. They knew the doorman’s name and his family’s story. In his day, William Thornton Patrick was well known in Grand Island.

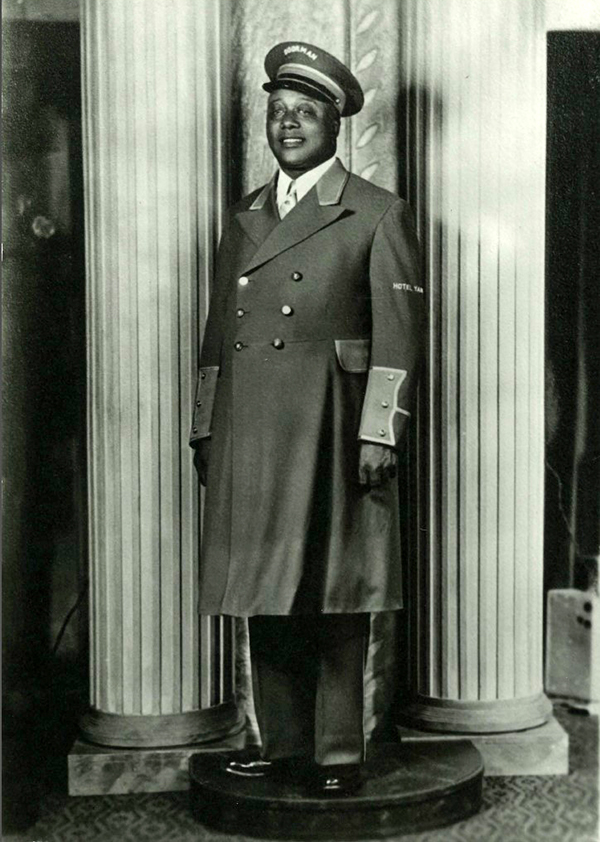

Here he is in his hotel uniform in about 1938:

Photo courtesy of the Plainsman Museum

Mr. Patrick was born in 1885 in Hamilton County, Nebraska. His parents, David and Hannah, were the county’s first African American farmers. Formerly enslaved, David was said to have been a Pony Express rider as a young man. David became a respected citizen in Hamilton County—for example, in 1886 he was elected president of the Lincoln Valley Cemetery Association Board. Hannah had been a schoolteacher in Missouri before she married.

As a young man, William Patrick farmed, and then worked at the Union Pacific shops in Grand Island before becoming a hotel doorman at the Yancey. He held that job for the last twenty years of his life. His wife died a few years before this photo. They had a daughter who moved to Los Angeles.

“The Yancey hotel won’t seem quite the same without Pat at the door,” reads an unidentified newspaper clipping after Patrick’s death in 1952.

William Patrick was a doorman in the grand manner. Impressive in appearance with his great bulk encased in a royal blue uniform, he made the welcoming of guests to the hotel an occasion of the moment, and he made them feel that they were highly important.

He had a great memory for names and faces, and it is always flattering to be remembered—especially by a functionary of the type of Pat.

For many years he was the hotel’s doorman, and during those years he made hundreds of friends, who will miss his genial presence.

William Patrick was obviously well known and well liked in Grand Island, and he rose about as far in society as he could expect. As I wrote earlier, jobs as doormen or porters were among the best available to Black men at that time.

One wonders what he might have done in a less racist society. Despite his mother’s background, census records indicate that Patrick got no further in school than the fourth grade. That wasn’t unusual when he was a child, but it was usually a mark of economic necessity.

But he developed skills outside of the classroom. When I read about his remarkable memory for names and faces, I was reminded of three-time presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan, who impressed people with the same ability. Patrick was gregarious, understood what business travelers wanted and made them feel important. With white skin, such a man might have had a much different career, might have become mayor of Grand Island for all we know.

As it is, Patrick seems to have made the most of the hand dealt to him. He is buried at his family’s cemetery plot in Aurora.

(Posted 2/4/2021. Read Part 1 here.)

Thank you to Kathryn Larson, social media intern at the Plainsman Museum, for sharing information from the museum’s files.