By David L. Bristow, Editor

World War I was fought not only with weapons but also with pictures and words. After the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the federal government began using advertising and propaganda on an unprecedented scale, employing advertising professionals to sell the war the way they sold automobiles and phonograph records.

Posters were an effective way to communicate directly with the public. Colorful and cheap to produce, they blanketed the country with wartime messages. Street photos of the period often show various war posters tacked to fences and buildings, in cities and small towns alike. Bold in design, posters conveyed their message at a glance and aimed for a strong emotional response.

Addison Sheldon of the Nebraska State Historical Society (today’s History Nebraska) collected dozens of posters in the States and in Europe during the war. The few shown here portray women in ways that offer insights into the place of women in the context of wartime goals and cultural norms.

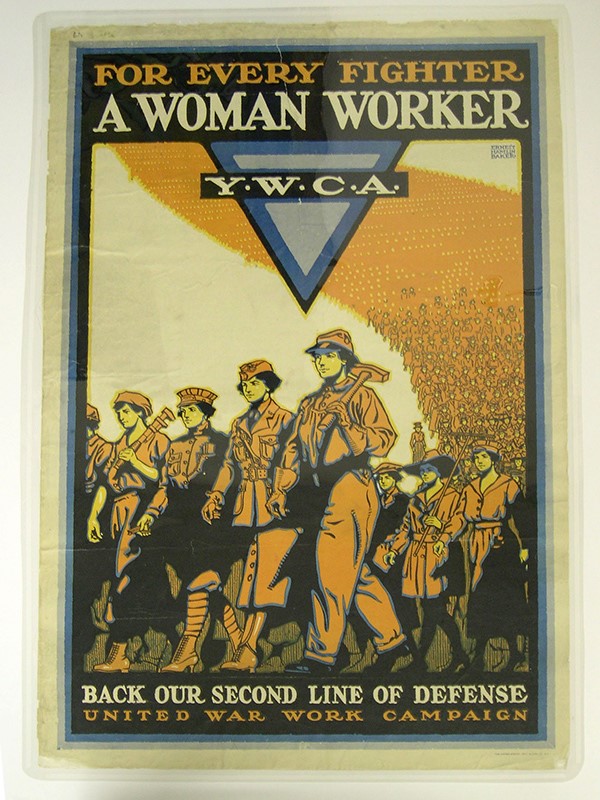

Today it’s hard to appreciate how 1910s sensibilities would have been shocked by regimented women in trousers, carrying sledgehammers and monkey wrenches. This blurring of gender roles was portrayed as a temporary patriotic duty—as it would be again in World War II.

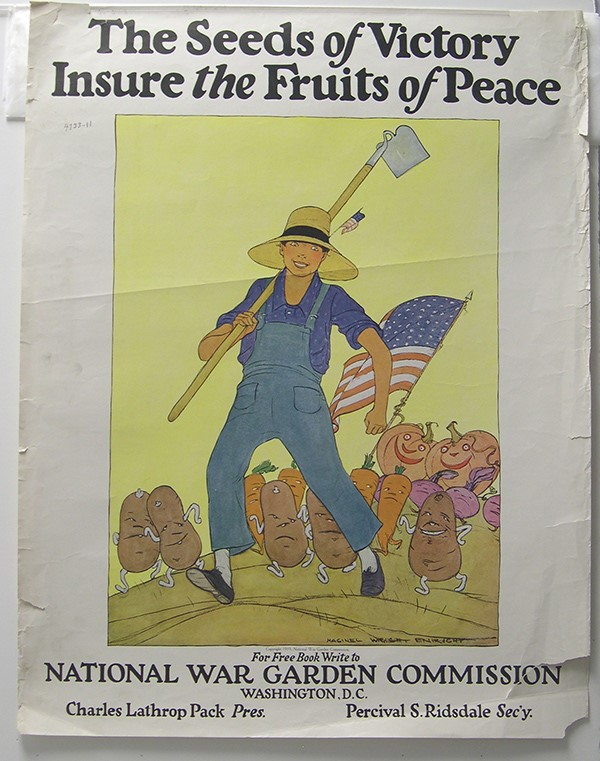

In a far milder gender-bending scene, a cheerful gardener carries her hoe like a rifle while leading her little army of vegetables. She, too, is a warrior, but a non-threatening one:

Women were also portrayed in more traditional roles. Here, the woman is the gentle wife to be defended by the man:

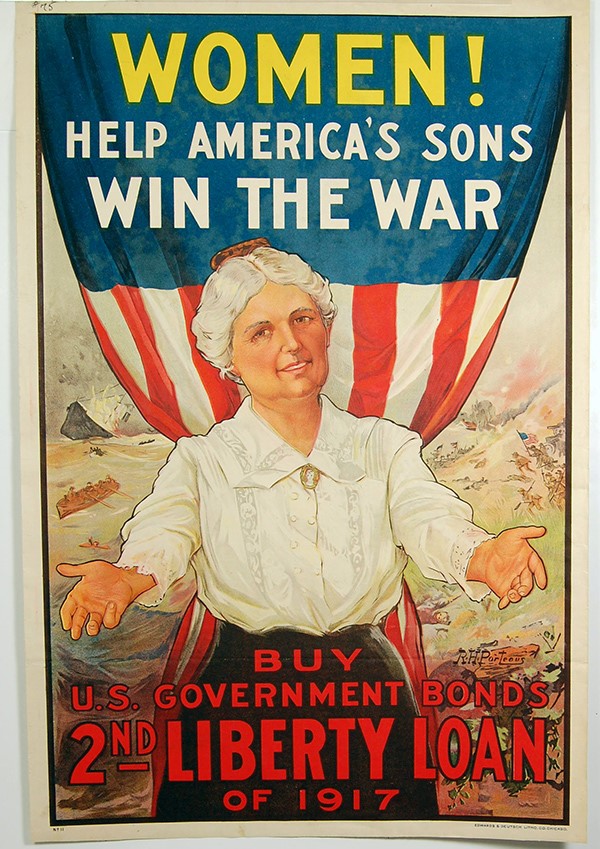

Here she is the aging mother still caring for her sons:

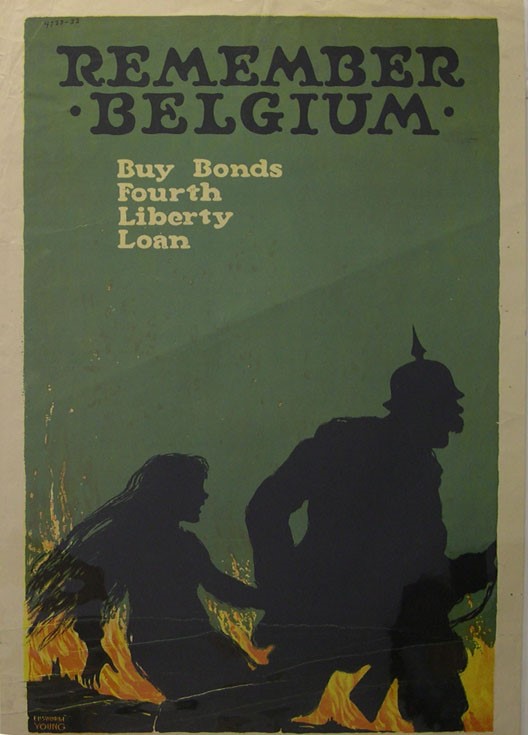

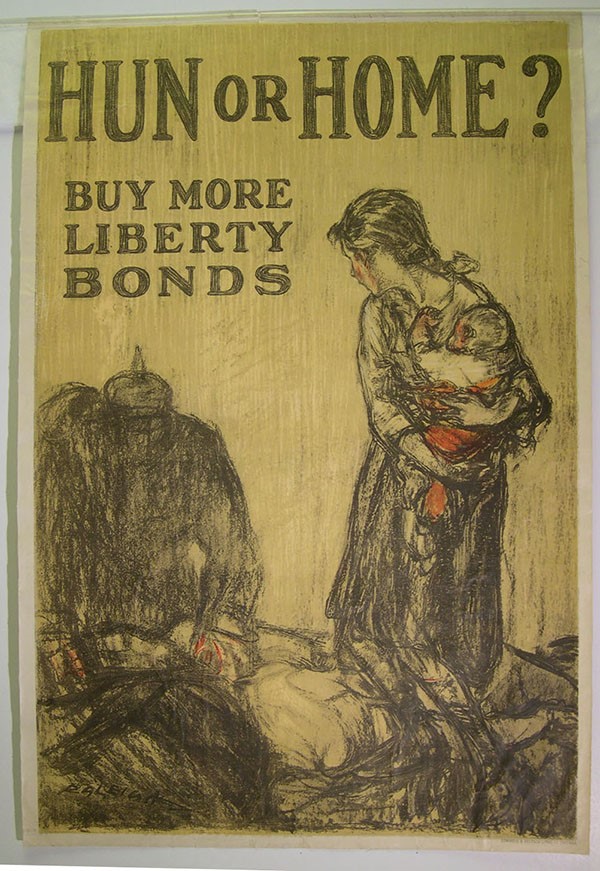

Here she is the anonymous rape victim of “the Hun.” German atrocities in Belgium—both real and exaggerated—during the war’s opening campaign provided endless fodder for Allied propaganda:

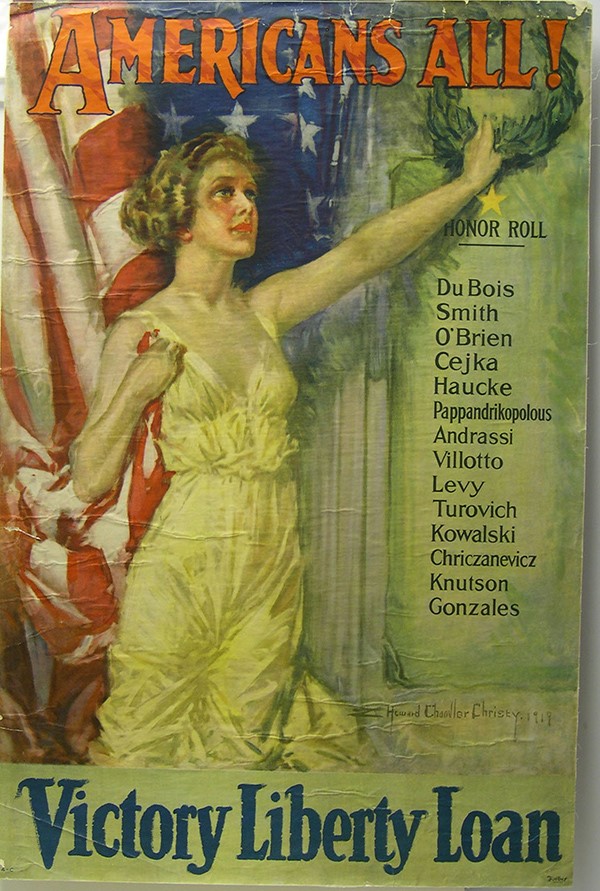

In her clingy dress, the model blends two archetypes: the laurel-bearing woman from classical art and the modern “Christy Girl” from magazine ads. Here she is eye-catching bait for a list of foreign names. More than twelve million immigrants had entered the U.S. since the turn of the twentieth century. Could such an ethnically diverse nation unify for war?

And finally, the woman is the symbolic (though saintly) warrior:

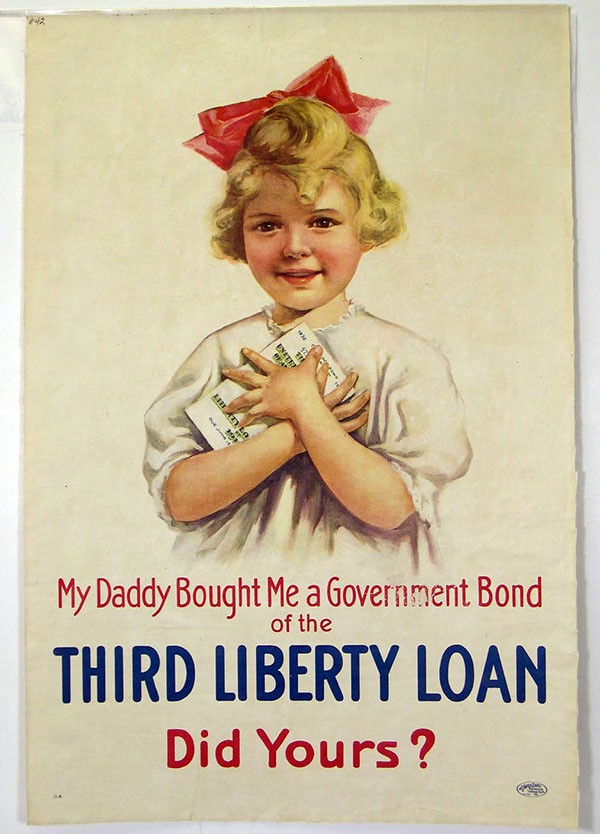

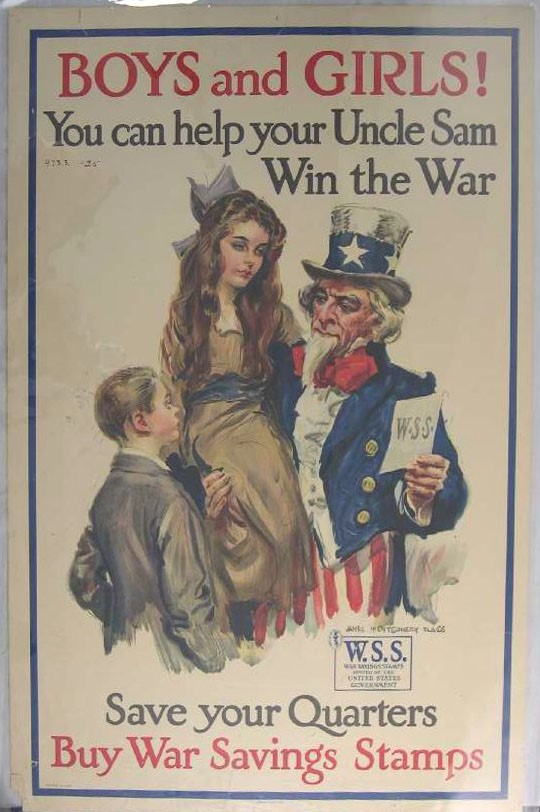

Here are some other WWI posters from our collections featuring women and girls. The United States partly financed the war through sale of Liberty Bonds, issued in four “Liberty Loans” in 1917-18. The federal government promoted buying bonds as a patriotic duty, using posters, celebrity appeals, and community efforts to create intense public pressure to buy bonds.

The U.S. didn’t institute food rationing in World War I (as it did in World War II), but instead relied on public relations campaigns to promote “meatless” and “wheatless” days and other measures to conserve food.

(A version of this article first appeared in the Oct-Nov-Dec 2017 issue of Nebraska History News.)