“Edward Kuehl, one of the most peculiar characters that ever lived in Omaha, or anywhere else, was found dead in his bed last night in the back room of his place of business at 319 South Tenth street,” said the Omaha Daily Bee on March 1, 1887. Kuehl, a cobbler who was popularly known as “The Old Shoemaker,” also styled himself a fortune teller, a “Magister of Palmystry and Conditionalist,” according to his longstanding advertisement in the Bee.

Kuehl freely admitted to his friends that “his art was a harmless humbuggery, to which he held because it was more profitable than shoemaking. His patrons were numerous, and included the representatives of all classes of society, especially of the weaker sex. Unfortunate girls and women of ill repute found comfort in his forecast of the future, while fashionable ladies paid liberal bills to ‘The Old Shoemaker’ for work that did more to quiet troubled conscience and solace discontented spirits than to cover dainty feet. No one was willfully deceived by him, and those who paid him fees did it generally in the face of his own candid statement that he could give no tangible reason why they should believe any of his forecasts.” The Bee also noted that Kuehl, who had died of an overdose of morphine, requested in his will that his body be cremated.

The following day the Bee reported a surprising development at the inquest: A friend who had witnessed the signing of Kuehl’s will containing the cremation request said “that he [Kuehl] wanted his ashes put in a bottle which was to be placed on the bar in Ed Wittig’s saloon.” Readers must have wondered if the request was in earnest. The Bee‘s “Sunday Gossip” column on March 6 said of Kuehl: “No one enjoyed a practical joke better than he. In fact his whole life in Omaha was made up of practical jokes, as he termed his mysterious practices. He wound up his career with a practical joke by making a will that his remains should be cremated, and that his ashes, collected in an urn, should be placed over the bar of a popular saloon. His wish in this matter will be strictly carried out.”

However, some of Kuehl’s friends were having second thoughts. On March 19, John Baumer, who had arranged for the cremation in Buffalo, New York (because a crematorium was not then operating in Omaha), told the Bee that the Old Shoemaker’s ashes “are now at Drexel & Maul’s [mortuary], in a neat clay-red urn, hermetically sealed. Mr. Baumer says that Kuehl never desired that his ashes should be placed in Wittig’s saloon, and the idea originated from a serio-facetious remark of a bystander at the coroner’s inquest, when the announcement was made that the body was to be cremated; the funny man said the ashes ought to be spread on Wittig’s grave. Mr. Baumer never for a moment entertained an idea involving such a sacrilege. He is in correspondence with the heirs with a view to buying a lot in the cemetery and burying the globular vessel and contents.”

Whatever Kuehl’s final wishes may have been, his ashes never graced the interior of Wittig’s saloon. Ed Wittig told the Bee on March 26: “Kuehl never made any request that his ashes should be placed in my bar. If he had, I would have most certainly carried it out.” The Bee noted several years later, on February 7, 1890, that the ashes were still at Drexel and Maul’s undertaking establishment “and are now to be found on a shelf in the cellar of that house.”

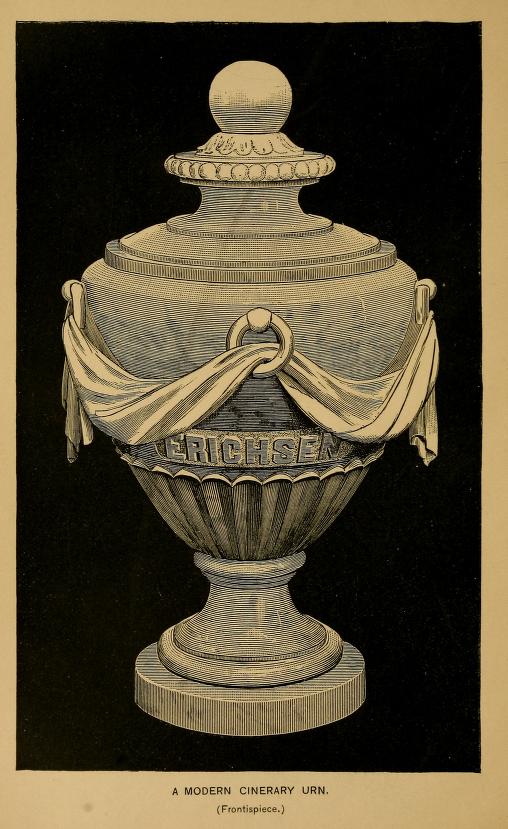

This example of a cinerary urn is from Hugo Erichsen’s The Cremation of the Dead (Detroit, 1887), published the year Edward Kuehl died.

(November 2011)