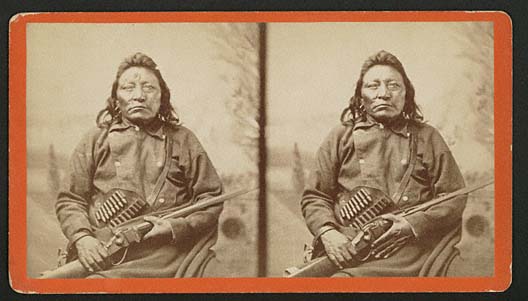

Red Dog, an Oglala Lakota who lived at the Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska, 1876-77 (Nebraska State Historical Society RG2955.ph).

In the summer of 1876, following the defeat of Lt. Col. George A. Custer at the Little Bighorn, the United States Army took control of the Sioux Indian agencies in Nebraska and Dakota Territory. Allegedly the agency camps were serving as sources of supplies and reinforcements for the warring Sioux who had annihilated Custer, and the military intended to put a stop to this aid. One by-product of this new army administration was the preparation of accurate census records to determine exactly how many Indians resided at Red Cloud, Spotted Tail, Cheyenne River, and the other Sioux agencies. Later, as the Sioux War of 1876-77 drew to a close and many of the formerly hostile bands began to drift into the agencies under pressure from pursuing army field commands, the military census records were expanded to include detailed registration of these surrendering bands. It is from these circumstances that the material presented here under the title The Crazy Horse Surrender Ledger came into being. The ledger, prepared under the supervision of two young army lieutenants, contains the administrative statistical record of Indian tribes belonging to the Red Cloud Agency, located near Camp (later Fort ) Robinson in northwest Nebraska. The contents of the Red Cloud military census are an important and exciting addition to the historiography of the Oglala branch of the Lakota and of the Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes who were attached to the agency during this time. To properly understand its value and to appreciate the riches contained within its covers, one could profitably read or reread the writings of George Hyde, Mari Sandoz, and James C. Olson to acquire familiarity with the events and personalities associated with Red Cloud Agency in the 1870s. From the historical foundation provided by these authors, the census ledger proceeds to enlarge our understanding of the human dimension of the Oglala experience during this important era. Thus, in addition to the light it sheds on military aspects of the Sioux War, the ledger also offers valuable detail about the families and social experiences of not only prominent Lakota leaders but also everyday, ordinary Indian people. We see, for example, the manner in which the military administration of the agency in 1876-77 helped contribute to the eventual breakdown of the traditional tribal structure among the Oglala Lakota. By February 1877 the army, ignoring the historic division of the Oglala tribe into seven principal bands, had divided the agency residents into first four, then six, large administrative units. These were identified either by traditional names (Kiyuksa, Wazhazha) or by the names of their chiefs or headmen (Red Cloud, Young Man Afraid of His Horses) or through a combination of the two. One such form of identification deserves notice here because of its rarity. In Lieutenant Johnson’s census, taken in February 1877, he listed the “Melt Band” under Yellow Bear as a major Oglala agency group. The only other reference I have ever seen to a “Melt Band” among the Oglalas are in statements by William Garnett, a mixed-blood who served as interpreter to both the military and Indian service at the Oglala agency. Garnett is listed as a member of the Melt band by Lieutenant Johnson (p. 80). The more familiar identification of this tribal group is the “Spleen Band” (Tapishlecha). Garnett’s usage of “Melt” (He probably was employed by Johnson in the taking of the census) is an archaic form of the term “spleen.” In Old English the word “milte” referred to the spleen; in Old High German the term is “miltzi.” One can only conjecture how such an archaic word form became part of Garnett’s vocabulary. Perhaps it was through his contacts with European-born Indian traders, such as the Swiss brothers Jules and Frank Ecoffey, who operated along the Platte River and married into the Oglala tribe. For readers acquainted with the history of the Oglala Lakota, there will be a number of familiar names carried on the pages of the ledger. Of particular interest to me are the entries for “Mrs. Twist” (pp. 21, 72), a full-blooded Oglala woman and the widow of Thomas S. Twiss, Indian agent for the Upper Platte Agency from 1855 to 1861. Twiss died at Rulo, Nebraska, in the early 1870s, and his family then joined the Oglalas at Red Cloud Agency. As the army officers visited the Twiss home–for the entry on page 72 carries with it an “h” notation which I believe to signify “house” or, more specifically, log cabin–one can only wonder whether either Lieutenant Calhoun or Lieutenant Johnson was aware that the late husband of the woman, and the father of the teen-age boys, Jimmy and Charles, who are mentioned on the census, was an honor graduate of the United States Military Academy. Twiss ranked number two in the class of 1826 at West Point and was a classmate of, among others, Generals Albert Sidney Johnston, Samuel P. Heintzelman, and Silas Casey of Mexican and Civil War service. The Twiss family was one of many listed in the census who belonged to the mixed-blood element of the Oglala tribe. Products of unions between white fathers and Sioux women, the mixed-blood offspring of these marriages were often inelegantly referred to as “half-breeds” and their fathers as “squaw men” in the written records of the period. In the census the male parent does not normally appear as a tribal enrollee, nor were they beneficiaries of the ration and annuity system, but their wives and children were so entitled. Thus, the entries are for Mrs. Twist, Mrs. Randall, and so on. One important characteristic regarding the place of these people in the tribe emerges rather clearly from the census records. The long-held and frequently asserted belief that all, or most, of the mixed-blood families were affiliated with the Oglala “Loafer Band” is clearly not correct. The “Loafers,” or “stay around the fort people” as they were sometimes known, were the Sioux groups who began to reside near Fort Laramie in the 1850s and 1860s rather than follow the traditional, roaming buffalo hunting existence of earlier days. The census does show that a number of mixed-blood families were living with the Loafer band in 1876-77 (pp. 66-67), but one can also find a large contingent among Young Man Afraid’s following (pp. 62-64). There are also such familiar mixed-blood households as the Shangrau in Red Cloud’s band, Janis and Stirks in Red Leaf’s Wazhazha camp, and Nelson, Salway (“Salois”), and Clifford with Little Wound’s Kiyuksas. From this it is clear that many mixed families were still associated with the tribal divisions to which the wife and mother in the household belonged, remaining a part of her traditional tiospaye (family clan or group) until the end of the 1870s. By then the Oglalas were located on the Pine Ridge Reservation, and the old camps and tribal divisions were eventually broken up and geographically scattered by government policies. As one reads through the pages, other familiar names meet the eye. Listed among the members of the Crazy Horse band is the name of White Twin (p. 163), a little-known but influential leader among the warring Oglalas. He was literally a twin, and his equally influential brother, Black Twin, was so identified because of a darker complexion. In Little Wound’s Kiyuksa band can be found the name of his father, Old Bad Wound (p. 1), the headman who was appointed tribal chief by Gen. William S. Harney at Fort Pierre in 1856. Two prominent Oglala tribal historians also appear, White Cow Killer (pp. 9, 79) and Cloud Shield (pp. 25, 66), whose winter counts were published by the Bureau of American Ethnology in its fourth annual report. Old Man Afraid of His Horses (pp. 17,62) is found to be still residing in his son’s camp at the agency. An outstanding leader during the 1850s and ’60s, his stature among the Oglalas may be measured by the nickname “Our Brave Man” as he was known to many of his people. And, finally, an entry for Sitting Bull’s family (p. 27) refers to the southern Oglala warrior leader and not the better known Hunkpapa Sioux of the same name. At the time of the Calhoun census, the Oglala Sitting Bull was on a peace mission to the northern groups, a journey from which he never returned. He was treacherously murdered by Crow scouts at an army cantonment on the Yellowstone River in December 1876. Another important aspect of the Sioux War of 1876-77 upon which the ledger casts a revealing light is the fighting strength of the warring Indians during the conflict and particularly at Custer’s defeat on the Little Bighorn in June 1876. From almost the date of the engagement, writers have claimed a huge number of lodges for the Little Bighorn camp and calculated each to contain, as a general rule of thumb, two warriors per lodge. This would explain away the defeat of the Seventh Cavalry by what had to have been, numerically, a vastly superior foe. More recent studies of the question have taken a more modest approach to the size of the Indian fighting force but have not always possessed enough accurate statistical data to document the strength of Custer’s conquerors. The Crazy Horse surrender ledger helps on this point, containing as it does, reliable documentation on one large group that was clearly part of the hostile force–namely, the party which surrendered at Red Cloud Agency under Crazy Horse in May 1877. An analysis of the make-up of this group of 145 lodges and 217 adult males provides the following breakdown:66 lodges contain one adult male warrior 43 lodges contain two adult male warriors 20 contain three or more adult male warriors 16 contain no adult males, only widows or old womenEven if one eliminates the widows’ lodges entirely, the average of adult males of fighting age is only 1.7 per lodge. If the lodges occupied by the old women are counted, the average is 1.5 warriors per lodge. This and other evidence clearly supports the belief that Custer and his Seventh Cavalry were defeated by a warrior force of superior fighting ability and not by overwhelming numbers alone. One other statistic of significance contained in these records concerns the impact the Sioux War had upon the young children in the warring camps. The enumeration of the agency bands (both Sioux and Arapaho, the latter being known to have remained at Red Cloud throughout the summer’s hostilities) discloses that the population of those peaceable groups averaged 52% adults and 48% children. In contrast, the Oglala and Cheyenne parties that had fought the soldiers during the summer, fall, and winter of 1876 and had surrendered at Red Cloud Agency contained an average of 58% adults and only 42% children. While other factors may help explain these rather significant differences, it also seems evident from this data that the pursuit by the military columns, attacks on winter camps, and the abnormal winter hunting opportunities took a deadly toll among the youngsters of the fighting bands. In his very useful introduction to the ledger’s contents Thomas R. Buecker has noted the vulgarities used to identify some of the Indians on the census lists. This practice, reflective of the sometimes coarse but good-natured humor of the Lakota, was not uncommon in this period. Late in the nineteenth century care was taken by officials at the Sioux agencies to clean up such personal identification before the official tribal census rolls were created for administrative purposes. Perhaps more of a problem in using this source while searching for individual identifications is the quite common Lakota practice of multiple personal names. One name might be a formal tribal identity–which could change with time and frequently did–while another could be a nickname used by friends or close associates. The census ledger does not deal specifically with such situations, but they did exist. For example, the pages enumerating the make-up of the large Crazy Horse party (pp. 163-70) include the name of Crazy Horse himself, his uncle Little Hawk, Little Big Man, He Dog, Black Elk, and other prominent figures in the camp. But not to be found is the name of Big Road (or Broad Tail), a headman in the Oyukpe band who led many of these same Oglalas in their “break-out” to a Canadian exile during the winter of 1877-78. He must have come in to the agency during the surrenders of the previous spring but under some other identification. In the case of the aforementioned White Twin, he is listed under that name in the ledger, but the Amos Bad Heart Bull pictorial record and the editorial notes accompanying that volume (Helen H. Blish, A Pictographic History of the Oglala Sioux, University of Nebraska Press, 1967) also state that he was known by another name, Holy Buffalo. The ledger shows further that the He Dog household (p. 170) included four other adult males in his lodge, all of whom are named. Some, if not all, of these men were probably brothers of He Dog, yet none of the identities recorded here–The Lights, Crawler, Clown No. 2, Wound in Back–match the names for He Dog’s siblings in the very detailed and authoritative record kept by Amos Bad Heart Bull, a relative of He Dog. All circumstances considered, one suspects that at least some of the brothers identified by Bad Heart Bull were with He Dog when the military made the ledger entries in 1877, but they are listed in the census by names other than those recorded by Bad Heart Bull. This would suggest that the Crazy Horse surrender ledger, while an immensely valuable and important historical source, is not, as it stands, the final word on some of the topics with which it deals. Perhaps the greatest contribution made by the publication of the ledger is to bring the imaginative reader into personal contact with the Sioux, Cheyennes, and Arapahos residing at Red Cloud Agency in 1876-77 and to convey a new appreciation of these people as families of men, women, boys and girls who played roles, some significant and some unimportant, in the historical events of that era. To the credit of the Nebraska State Historical Society, it was able to follow up the acquisition of this remarkable record with a publication that will reach a wide audience of appreciative readers, both Indian and white.Harry H. Anderson Milwaukee County Historical Society Milwaukee, Wisconsin