Imagine yourself as a pioneer living in a hole in the ground. Now imagine that floodwater is rising toward the ceiling. Welcome to rural Boone County in 1873.

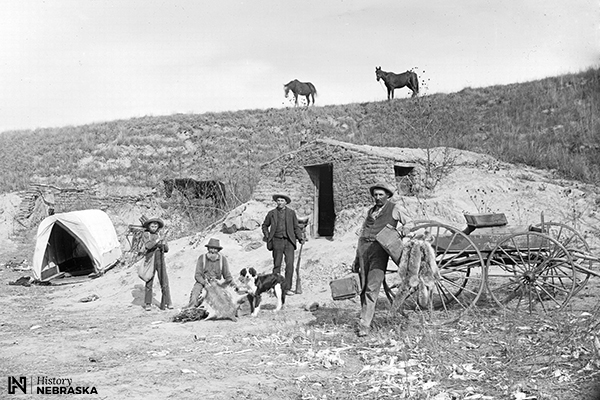

Photo: “Keeps Bachelors Hall,” wrote photographer Solomon Butcher of these men near Ansley, Nebraska, in 1888. History Nebraska RG2608-0-1397

By David L. Bristow, Editor

Imagine yourself as a pioneer living in a hole in the ground. Now imagine that floodwater is rising toward the ceiling. Welcome to rural Boone County in 1873.

The sod house is iconic of Nebraska’s frontier period, but many pioneers started out in an even simpler form of housing—the dugout. Historian Everett Dick described how to build one in his 1975 book Conquering the Great American Desert. In short: dig a rectangular hole into a hillside or a ravine. The open side should face east to catch the morning light and so that snow will blow away from the door. Enclose the open front with a wall of logs or sod. Leave a space for a door; a window is optional. Roof the hole with “poles, brush, hay, and earth.”

Your house will be cheap, quickly built, cool in summer, and warm in winter. It will also be cramped, dark, dirty, and full of every critter in the ground. But it will do until you plant your first crop and have time to build a proper soddy or frame house.

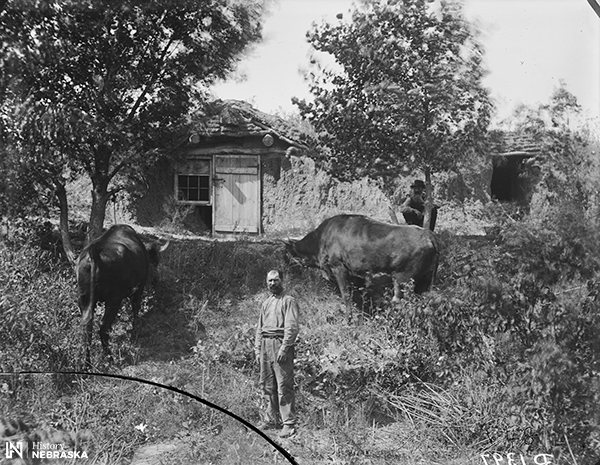

Photo: Near McCook, Nebraska, 1890s. H. W. Cole Collection, History Nebraska RG3464-0-3

Depending on their location, dugouts had a more serious drawback. Many settlers dug them into a high bank beside a creek, where you had a steep slope plus water and timber nearby.

John Turner dug such a house in Boone County. A neighbor told him the spot was high enough even if the creek should rise, and Turner lived there with his wife and three boys while he built a sod house on another part of his claim.

But Turner, a recent immigrant from England, didn’t expect the severity of the thunderstorm that struck one day while he and the two older boys worked on the soddy. He sent 12-year-old Edgar back to the dugout to check on his wife and youngest child. Edgar soon came back hollering and waving his hands.

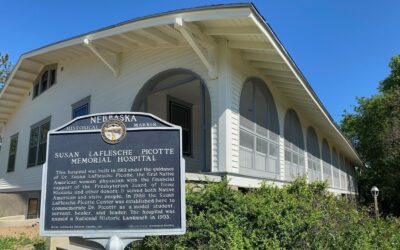

Photo: Home of D. Meek, south of Broken Bow, 1890. Photo by S.D. Butcher. History Nebraska RG2608-0-1610

Turner ran for the dugout and waded through the rising water, struggling to keep his balance against the current. The dugout itself was flooded. Inside, Mrs. Turner sat on one of the wooden doors the family was using as temporary flooring. Balanced on a floating door, she held the youngest boy while holding a frying pan over his head to protect him from the rainwater pouring through the roof like a sieve.

“Higher and higher the two caged birds were lifted till their heads almost touched the roof,” Turner wrote years later.

He had to get them out quickly. He grabbed the little boy, waded across the creek, and left the child on high ground. Then he went back for his wife.

Turner was carrying his wife across when he stepped in a hole, stumbled, and dropped her into the rushing water. Somehow, he stayed on his feet and grabbed hold of her dress.

“We scrambled and struggled through to the other side the best way we could,” he wrote.

The Turners lost most of their supplies, but escaped without loss of life. They stuck it out on their claim, and in 1903 Turner published a memoir, Pioneers of the West, recounting this and many other hardships that the family met with a combination of hopefulness, ignorance, and fortitude.

Photo: Roten Valley, Custer County, Nebraska, 1892. Photo by S.D. Butcher. History Nebraska RG2608-0-1677

Posted 3/1/21. This article first appeared in the April 2020 issue of NEBRASKAland magazine.

Sources:

Everett Dick, Conquering the Great American Desert (Lincoln: Nebraska State Historical Society, 1975), 25.

John Turner, Pioneers of the West: A True Narrative (Cincinnati: Jennings and Pye, 1903), 72-79.