Ford Conservation Center staff recently worked on bringing an almost 150-year-old family heirloom back to life. This project was a framed homestead certificate, which required treatment from our objects lab and paper lab.

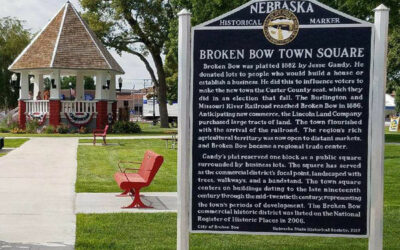

The bulk of the project’s historical significance was in the document, an 1875 homestead certificate granted to Nebraskan Charles Henry French by the Ulysses S. Grant administration.

This document and frame tell a very important piece of the French family history, and they have been passed through several generations of Charles Henry French’s family. He was the son of a wood carver named William Benjamin French and Sara Leah Marcellus French. The couple left their home in New York around 1833, heading west in a covered wagon. They had 11 children, but only four survived to adulthood.

Charles was born in 1835. By this time, the family had reached Adrian, Michigan. When he was grown, Charles and his father filed for a homestead in Filmore County, Michigan. There, Charles Henry married Sarah Spaulding in 1860. In 1862 after William Benjamin’s death, Charles Henry French continued moving west with his wife and mother, settling in Nebraska around 1870. Charles and Sarah raised four children in Washington County, Nebraska, on their homestead. The farm would stay in the family for 126 years – Charles Henry French’s grandson eventually had to sell the land when his health began to fail.

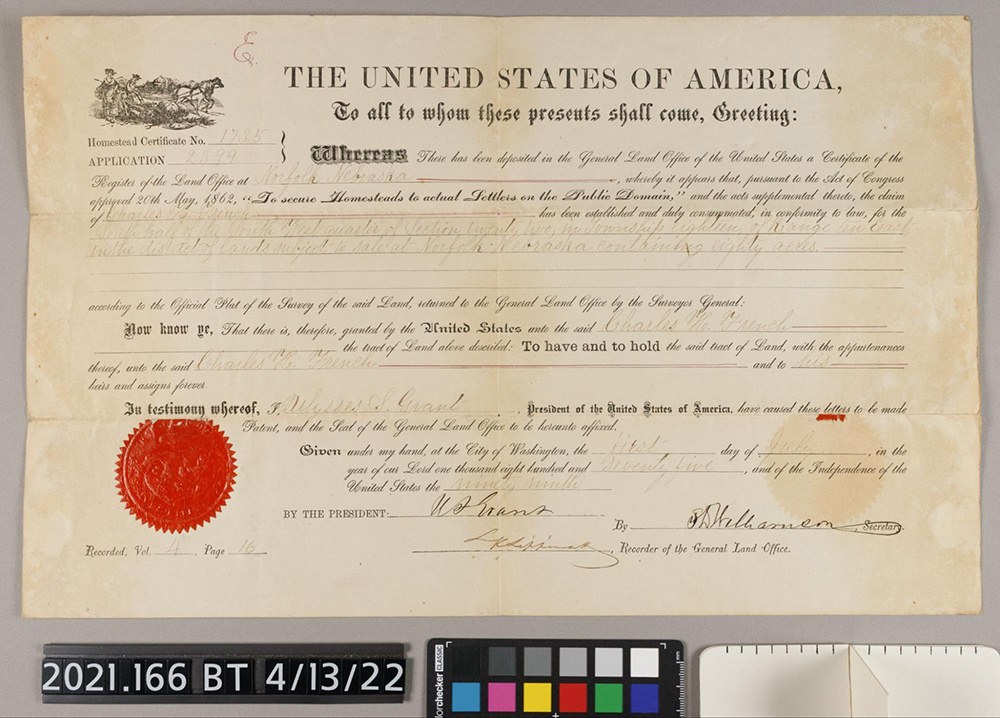

The certificate was in good condition overall but showed signs of wear and soiling. The first step was to dry surface-clean the document with soft sponges to reduce particulate matter and grime. Flyspecks, or insect waste, and other accretions on the paper’s surface were removed using scalpel blades.

In this image taken before treatment, the damaged seal and weakened creases (along the left edge) are visible.

The document had been folded in the past to fit into a small envelope, and tears had appeared along the creases at the edges of the paper. These tears were repaired with paper mends from the back to prevent further damage. While the document was folded, a small section at the top of the seal had torn and became stuck to the other side of the document. This piece was carefully removed and adhered in its original location.

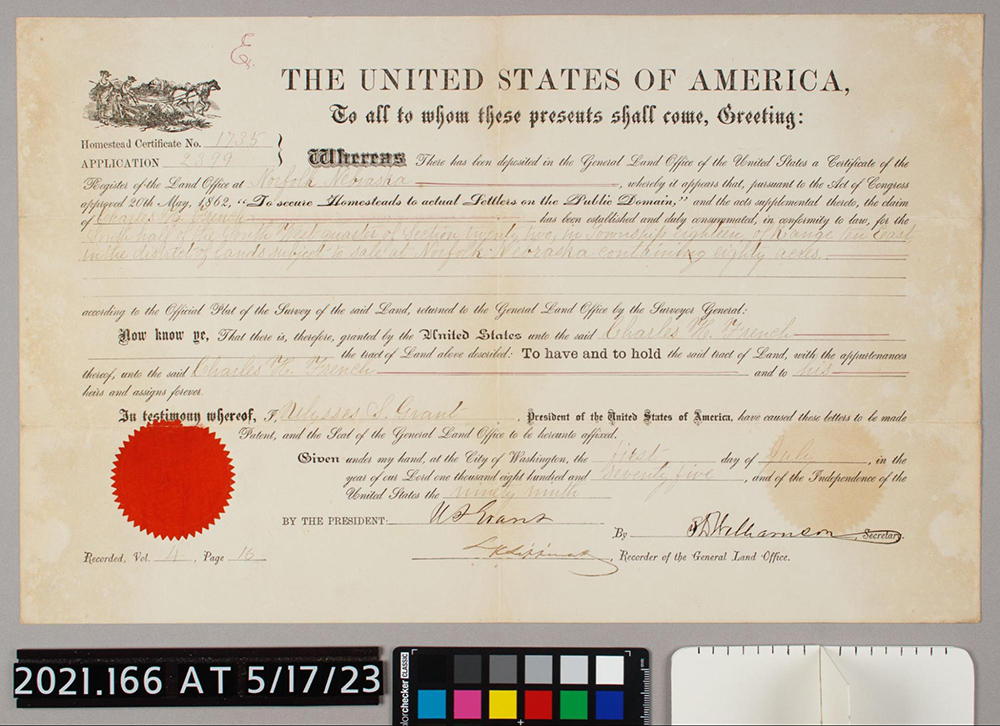

Finally, the certificate was humidified and flattened to relax the creases and distortions. To do this, the document was placed in a humidification dome. This conservation equipment allows tiny droplets of aqueous moisture to be slowly introduced so the paper fibers can gently expand as the paper becomes humidified. Following humidification, the lightly damp document was placed between absorbent blotters and light weights to dry as flat as possible in preparation for matting and reframing.

After treatment, the document is cleaner, creases are much less visible, tears have been stabilized, the seal has been reconstructed, and it lays flat.

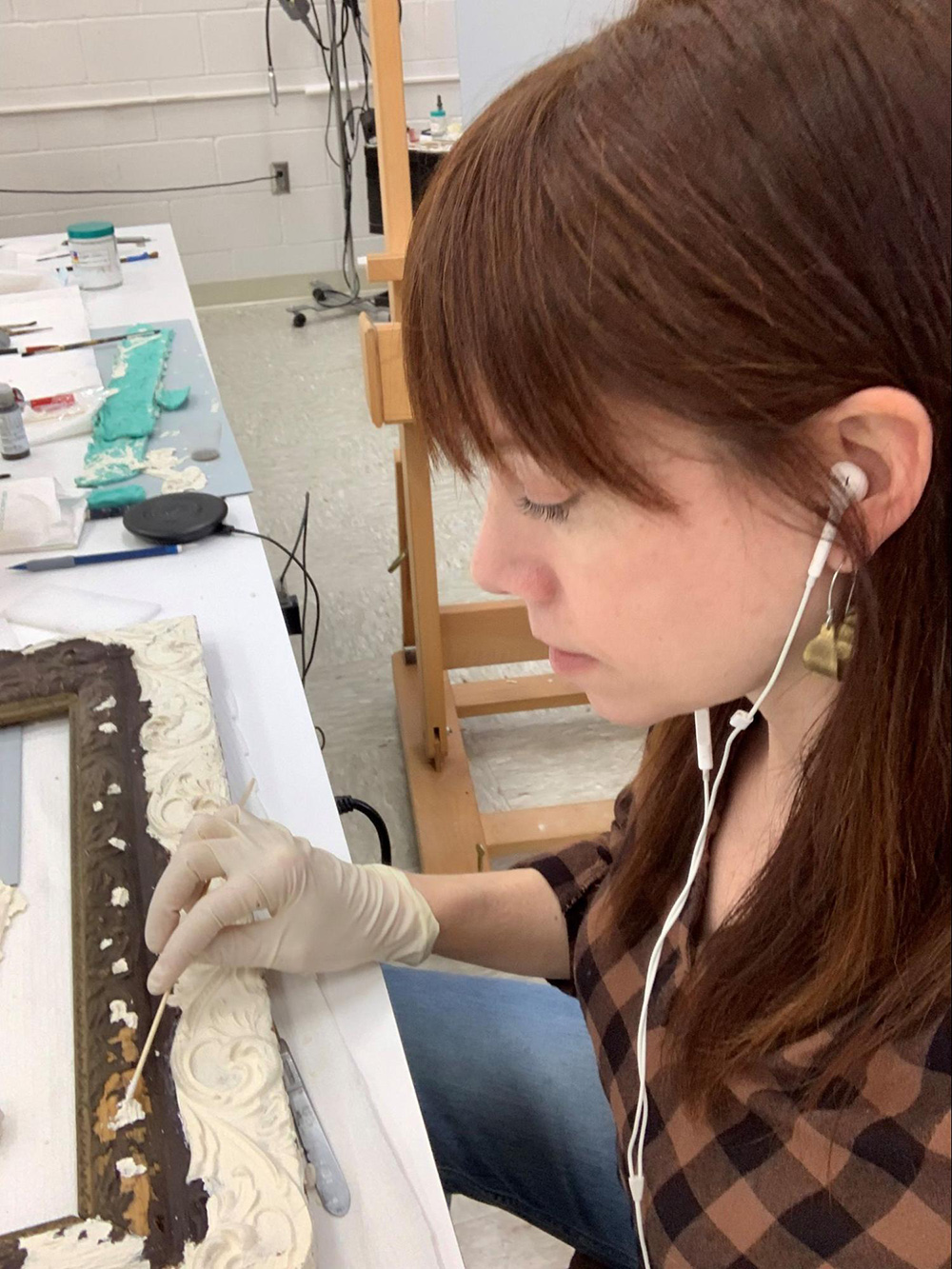

However, the bulk of the damage was to the certificate’s frame. It was original to the certificate and had certainly been through a lot. The four wooden rails featured painted decorative scrollwork made out of the composition. Luckily, much of the ornamentation was still intact, but it was almost entirely missing from one side of the frame.

In this before-treatment image, it’s very easy to see the extent of the missing composition ornaments.

The first step of the treatment was to stabilize loose pieces of the original composition ornament that were in danger of falling off of the frame.

The next step was to reconstruct the missing ornamentation. They were sometimes created by hand, using an appropriate putty over a barrier layer applied to the wood. Silicon rubber was used to create molds of the intact ornamentation for larger sections where intricate ornamentation had been lost. Wood putty was cast into these molds to create replacement sections. These cast pieces were then reshaped as necessary and adhered to the bare wood using an appropriate adhesive.

Once the ornamentation was fully reconstructed, it was toned and painted to match the original sections as closely as possible.

A combination of resins and dry pigments were used to match the frame’s matte finish.

Now that the frame and certificate have been restored, they are much more stable over the long term, and they can be displayed and shared by Charles Henry French’s great-grandchildren and their families.

The treated certificate was matted and re-framed using conservation-grade matboard and acrylic and returned to its owner.