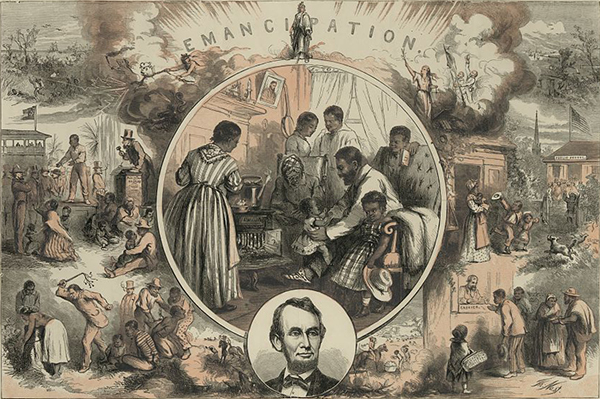

An 1865 engraving by Thomas Nast reflects the optimism of the time. Library of Congress

An 1866 letter shows us something that’s often forgotten when people talk about civil rights history. D.H. Kelsey of Plattsmouth was living in Washington, DC, when the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, was ratified following the Civil War. (See below to learn how the 13th Amendment differed from the Emancipation Proclamation.) The Nebraska Herald published his letter on January 3, 1866.

Kelsey praised the “great work of national regeneration,” adding that for the formerly enslaved people, “it becomes a great and pressing question whether they shall be entitled to equal civil rights… and it seems to be the growing opinion in all the departments of Government, that manhood and merit—not color or caste—should be the test of political rights or civil immunities.”

Hope for full equality in the 1860s? It sounds more like hopeful talk from the 1960s.

Kelsey’s letter is a good example of the spirit of northern optimism and egalitarianism that flourished at the war’s end. In 1867 Congress forced Nebraska to drop a whites-only voting provision in its constitution as a condition of statehood. Then in short order the states ratified the 14th Amendment (1868; equal protection under the law) and the 15th Amendment (1870; equal voting rights for men).

But the reason Kelsey’s optimism sounds so premature is that Americans allowed the civil rights achievements of the 1860s to be mostly whittled away by 1900—leaving future generations to struggle for what Kelsey thought his generation had already won.

Here are more excerpts of Kelsey’s letter:

“[T]he great work of national regeneration has been accomplished. The nation, baptized in fire and blood, has arisen to a new birth, and to a high and holy destiny. The hydra-headed and hundred fisted monster, ‘Human Slavery’ has fallen accursed of God and man, and the Republic now stands ‘redeemed,’ regenerated, and disenthralled by the genius of Universal Emancipation. While we mourn with those that mourn, let us also rejoice with those that do rejoice. The Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln, like John the Baptist, heralded and prepared the way of deliverance; and yesterday, by the glorious announcement of the Secretary of State, the crowning act is announced by the Constitutional Amendment de jure and de facto. ‘Glory to God in the highest! Peace on earth: Good will to men.’

“As all men, regardless of color or caste, are now secured in the enjoyment of their equal Natural Rights, it becomes a great and pressing question whether they shall be entitled to equal civil rights, in other words, whether artificial distinctions, merely on account of the texture of the skin or cuticle shall be removed; and it seems to be the growing opinion in all the departments of Government, that manhood and merit—not color or caste—should be the test of political rights or civil immunities. . . . [I]t is deemed especially important now, in the process of reconstruction and regeneration, to confer upon the loyal black man the civil privileges that are accorded to the unrepentant, disloyal white man. It is devoutly to be hoped that this matter will be settled on the principles of equal justice—that no hateful seeds of discord will be allowed to germinate and send their baleful influences through the restored Republic, so as again to threaten and culminate in the horrors of a civil war.”

* * *

But didn’t the Emancipation Proclamation end slavery in 1863?

While the Emancipation Proclamation applied to “persons held as slaves” in states or parts of states “the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States” as of January 1, 1863 (the Confederacy), it did not end slavery in the nation as a whole. The proclamation didn’t apply to states that hadn’t seceded, or to Confederate areas in Union hands by 1863. Lincoln didn’t believe that the Constitution gave the president the authority to end slavery, so he justified the Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure under his powers as Commander in Chief of US armed forces. He advocated a constitutional amendment as a permanent solution. Both houses of Congress passed the amendment, which then had to be ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the states. The process began during the Civil War and ended months after the war’s conclusion.

A brief timeline of 13th Amendment events:

Apr. 6, 1864: Senate passes the amendment 38-6

June 15, 1864: House defeats the amendment 93-65 (lacking a two-thirds majority)

Dec. 6, 1864: Lincoln’s message to Congress, urging reconsideration

Jan. 31, 1865: House passes the amendment 119-56 (subject of the 2012 Lincoln movie)

Feb. 1, 1865: Lincoln signs resolution submitting amendment to the states

(Lee surrenders Apr. 9; Lincoln is assassinated Apr. 14; last Confederate general surrenders June 23)

Dec. 6, 1865: Georgia ratifies, completing the process

Dec. 18, 1865: Sec. of State Seward announces that the amendment has been ratified

Adapted from “A Nebraskan Responds to the Thirteenth Amendment,” by James E. Potter, Nebraska History News, October-November-December 2015.