On January 1, 1863, Daniel Freeman filed the one of the first claims under the Homestead Act of 1862 in what is now Beatrice, Nebraska. When the Freemans built a cabin there, they became known as “America’s First Homestead Family”. The site of Freeman’s claim is now Homestead National Monument of America, a unit of the National Park Service.

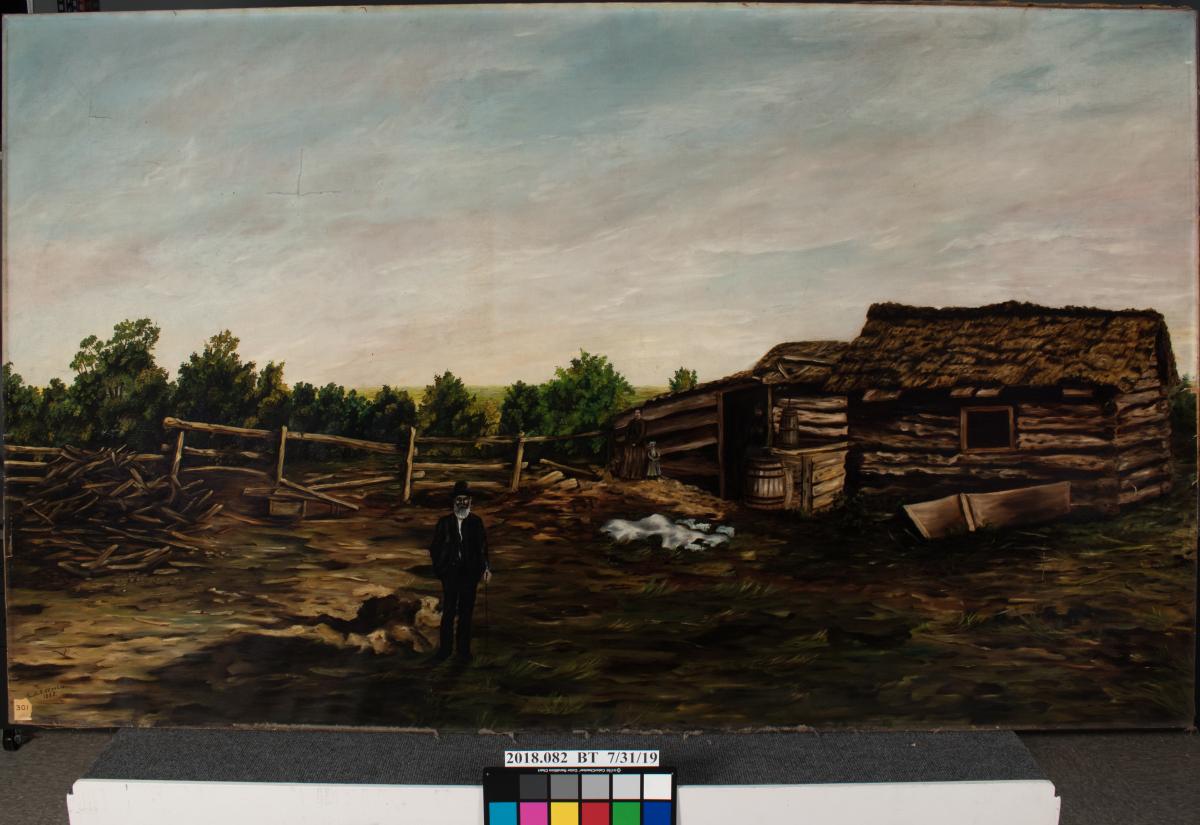

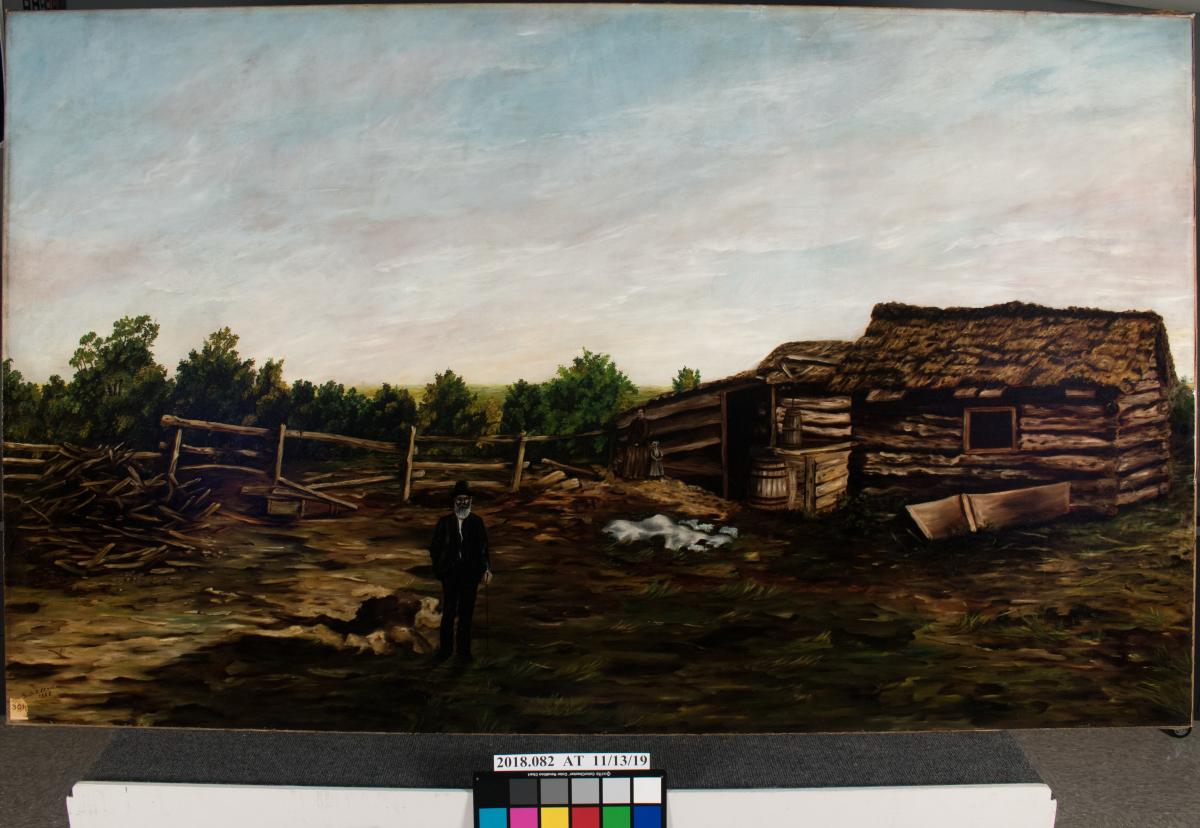

The Homestead painting before treatment. Years of dirt and dust have dulled and muddied the color of the sky.

Twenty-five years later, in 1888, Gusta R. Strohm, a resident of Beatrice, painted Freeman and his family in front of the cabin. The large painting (48″ x 80″), “The First Homestead”, had a nomadic life. It was displayed in multiple venues before it ended up in the U.S. Capitol building. It hung there before being placed in storage and forgotten. It was eventually discovered by a a Nebraska state representative who shipped it to the Nebraska State Historical Society (now History Nebraska) who eventually turned it over to Homestead National Monument of America. Using a grant from the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Friends of Homestead National Monument of America brought the painting to the Ford Center for treatment.

Before (left) and after (right) treatment, the painting was photographed in raking light (light shining parallel to the surface). Raking light shows the surface details of the painting, including holes, tears and planar distortions.

The 131-year-old painting was showing its age. The linen canvas was brittle and torn in a number of places. It was slack on its stretcher and was buckled. The oil paint had not been varnished and had darkened overtime from accumulated dirt and grime. The goal for treatment was to make the painting more structurally sound and clean it to restore the brighter colors of the artist’s intent.

The painting partially cleaned during treatment. You can see the darker area on the right side of the painting that has yet to be cleaned. The painting has been lined onto its new canvas.

As with all objects and artifacts that come in to the Ford Center, the painting was photographed to document the condition of the painting before treatment. Next, loose and flaking paint was consolidated with a specialized adhesive. Once the paint was secure, the canvas was removed from the stretcher and flattened to reduce distortions around the tears. The tears were mended from behind and the canvas was lined onto a new backing canvas using a heat set adhesive and the heated suction table. After the painting was safely lined, the painted surface was cleaned revealing the original colors beneath the grime. It was then attached to a new stretcher and a varnish layer was applied. The varnish layer not only brings out the original colors, but acts as a barrier layer for the fills in the loss areas. The losses were filled and toned to match the surrounding paint layer. The painting was reframed and after treatment photographs were taken.

After treatment, the colors of the painting appear brighter and the image is clearer.

During treatment, Nebraska Public Television came in on a regular basis to record painting conservator Kenneth Be’s progress. You can watch their story “A New Life for Old Paintings” and see additional photographs here: https://nebraskastories.org/videos/a-new-life-for-old-paintings/