Mari Sandoz (1896-1966), internationally known as a chronicler of the West and as an expert on Native American history, first gained fame as the author of Old Jules (1935), the story of her father and other settlers who came to the upper Niobrara region of Nebraska in the late nineteenth century. Mari was influenced a great deal by her father, Jules Sandoz, a Swiss immigrant, and by his acquaintances who visited the family homestead. She knew trappers, traders, Indians, and Indian fighters, and learned their stories and their backgrounds, which she later wove into her writings.

Upon the death of Jules Sandoz in 1928 his daughter began to work on a biography of him. This book, Old Jules, was completed in 1933, but was rejected by the publisher to whom she sent it. The book was rewritten and then resubmitted on several occasions, and each time was rejected until March 1935, when it won the prize for nonfiction in an Atlantic Monthly contest. Publication brought critical acclaim, and paved the way for future literary successes.

The University of Nebraska’s well-known geologist and paleontologist Erwin H. Barbour (1856-1947) was an acquaintance of both Mari Sandoz and her father, renowned for his crusty and cantankerous personality. In an April 30, 1936, letter to Blanch Ferrens Ball, Barbour recalled that after receiving several interesting paleontological specimens from Jules, “I jumped on the train and went up to northwestern Nebraska, but he had been called away on this occasion and so I failed to see him. Miss Mari at the time was about thirteen years old, very tall for her age and very slim. She and her brother, about eight or nine years old, tried to escort me across the plains and sand hills to the quarry [where the specimens had been found]. There was not a landmark in sight but they knew every inch of the way around the sand hills. . . .

“As you undoubtedly know, Miss Sandoz has been remarkably successful in writing an unusual book. . . . Dr. [Addison E.] Sheldon [of the Nebraska State Historical Society] asked Miss Mari why she put in her father’s mouth bad expressions that were repeated more than once. He said once ought to be enough, and she instantly replied that it would not be enough for my father. Everyone as far as I can tell counts this the truest piece of unbiased history of conditions as they were in her girlhood that has been attempted by anyone in the state. She didn’t sugar-coat any of the pills, she presented all of them just as they were.”

Barbour recalled that Jules Sandoz “was the best trained man in the community and [it] has always been very interesting to all of us that he should have persisted in growing fruits and the like where it was counted physically impossible to do so. Of course my knowledge of him was largely from passing, and rather hurried visits, but we had considerable correspondence. . . . Refined readers are apt to be shocked but it is the truth from beginning to end and some day someone is going to be very thankful that such a correct portrayal was made by Miss Sandoz.”

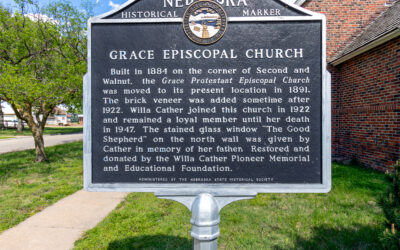

Mari Sandoz in 1935. NSHS RG1274.PH0-1

Jules Sandoz in his Sandhills orchard. NSHS RG1273.PH4-2