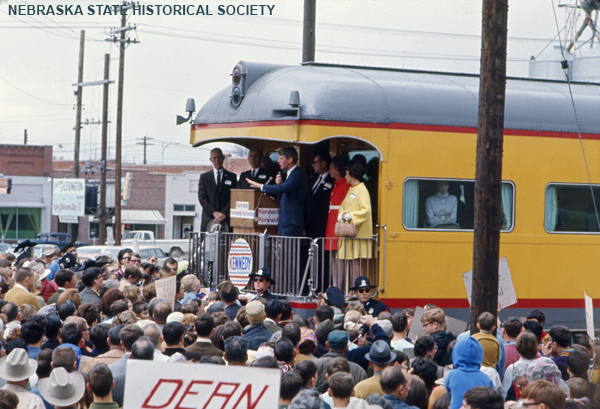

“I learned one thing I will never forget,” said Robert F. Kennedy on April 27, 1968, “It is a long way across Nebraska by train.”

Kennedy had just finished an old-fashioned whistle-stop campaign tour across the state (he is shown above in Lexington), part of the run-up to the crucial Nebraska presidential primary on May 14.

Wait. Nebraska—crucial?

Yes. The title of a 2005 NET Television documentary says it all: ’68: The Year Nebraska Mattered.

You can stop laughing, now, Iowa.

But the story is bigger than that. The year 1968 was one of the most turbulent in recent American history, and the campaign reflected the times.

Historian Gene Kopelson examined “The 1968 Nebraska Republican Primary” in the Fall 2014 issue of Nebraska History. Here we’ll look at the Democratic race between Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, Sen. Eugene McCarthy, and Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

Why Nebraska Mattered

In 1968 the modern primary system was not yet fully formed. Democrats held primaries in only 14 states, Republicans in 12. The national conventions chose the nominees. It had been this way since the 1830s.

It was still possible to win a party’s nomination without entering any primaries. (Eventual Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey would do so later that year.) Still, the primaries would go a long way in sorting a crowded presidential field, and Nebraska’s contest was early enough to draw national attention.

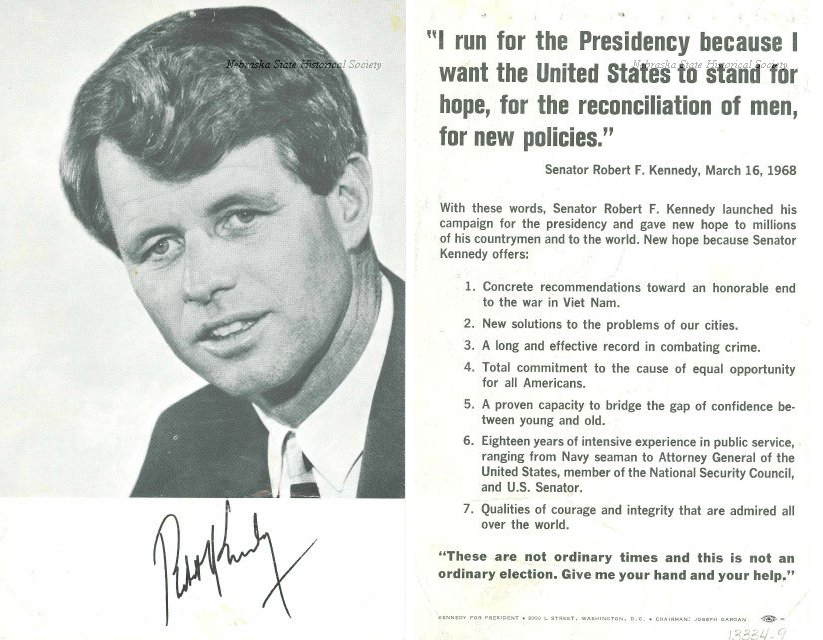

(Above: Campaign flier collected from Kennedy’s visit to Crete, Nebraska, May 1968)

RFK’s Whistle-Stop Tour

An estimated 31,000 Nebraskans saw Kennedy during his 11-stop tour on April 27. His train left Cheyenne, Wyoming, at 7:15 a.m. (Mountain Time) and stopped at Kimball, Sidney, Ogallala, North Platte, Lexington, Kearney, Grand Island, Columbus, Schuyler, and Fremont, before pulling into Omaha at 7:40 p.m.

Kennedy gave pretty much the same speech at each stop: emphasizing the need to preserve small towns and family farming, and to turn the fighting in Vietnam over to the South Vietnamese Army.

Not everyone who showed up was a fan. In Omaha a heckler shouted,

“Why don’t you back up the boys in Vietnam? You’d sell ’em out for a nickel.”

“I support them so much I’d like to see the South Vietnamese doing the fighting,” Kennedy replied.

Earlier that day in Grand Island someone held up a sign that read: “McCarthy Is No Opportunist.”

This was a dig at Kennedy. Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota had been the first candidate to challenge President Lyndon Johnson for the Democratic nomination. In the March 12 New Hampshire primary, McCarthy didn’t beat Johnson, but made a surprisingly good showing against the incumbent. LBJ looked vulnerable. Kennedy—who had already endorsed Johnson—announced his own candidacy four days later. Some called Kennedy an opportunist, saying he used McCarthy as a ‘stalking horse’ for his own campaign.

But Kennedy showed no displeasure at the Grand Island sign. He jokingly agreed that McCarthy was no opportunist.

“If he were an opportunist, he would be here in Grand Island.”

In fact, McCarthy’s campaign was busily organizing an “army” of young Nebraskans. That day 200 young volunteers came to Omaha for training in door-to-door campaigning. Young men were not allowed to have beards or long hair; young women dressed more conservatively than the fashionable miniskirt. Their slogan was “Clean for Gene.” Though he opposed the war, McCarthy didn’t want to be portrayed as the hippie candidate.

RFK at Creighton

Kennedy spent a lot of time in Nebraska that spring, making some half-dozen visits, with appearances in multiple communities. On May 13, a day before the primary, he stunned a Creighton University audience of 4,300 with pointed remarks about the Vietnam War and the draft (from which college students were exempt):

“…You say students should not be drafted. How can you argue that? How many black faces do you see here? How many Indians are at this university? How many Mexican-Americans? If you look at a regiment of paratroopers in Vietnam, 45 percent would be black… Will you work with me to bring whites and blacks together, to bring decent jobs, to bring decent housing for all?”

According to the World-Herald, “Many shouted yes, but there were some loud ‘no’ replies, too.”

That day Kennedy also made his case at 24th and Erskine Streets in the heart of Near North Side, Omaha’s black neighborhood. The area been torn by rioting following former Alabama Governor George Wallace’s campaign appearance in Omaha on March 4.

But Eugene McCarthy was also in town on May 13—and his brief visit to his campaign office at 24th and Charles sparked an hour-long parade and demonstration by 400 of his supporters. McCarthy repeated his ongoing challenge to debate Kennedy.

“I sought one in Indiana and offered to meet him at high noon in Scottsbluff. I said I was prepared to come alone,” he quipped. Kennedy ignored the challenge.

That night, Kennedy’s Omaha staff evacuated their campaign headquarters at the Sheraton-Fontenelle Hotel while police investigated a bomb threat. Police concluded it was hoax, and the story got a few paragraphs on page four of the next day’s paper.

The Results

Kennedy won the Nebraska primary the following day, defeating McCarthy 52 percent to 31 percent. It was his second primary victory.

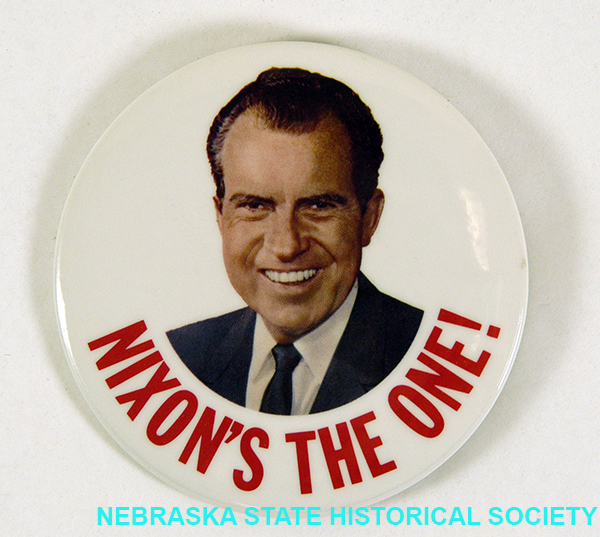

Kennedy was assassinated soon after winning the California primary; he died on June 6. Hubert Humphrey was nominated in August at violence-marred convention in Chicago, and lost to Richard Nixon in November.

—David L. Bristow, Editor

Watch a video of RFK’s 1968 Nebraska whistle-stop tour.

Sources:

“RFK Train Will Consist of Six Cars,” Omaha World-Herald, April 25, 1968.

“Kennedy Talks to 8,000 in Omaha,” Omaha Sunday World-Herald (Metropolitan Edition), April 28, 1968.

“Get Off Duff, RFK Tells C.U. Youth,” Omaha World-Herald, May 14, 1968.