As historians, the names we give to events are important. They imply interpretation but are also matters of consensus. This is a story of the ongoing debate over the name of a great tragedy at Fort Robinson.

Note: the word Indian is used instead of Native American as it was the norm at the time.

Imagine that you and your spouse and children and other relatives are being held in a freezing building with no food. Your captors are trying to break your will. They demand that you give up your home and let them take you to a concentration camp in a distant land. Some of your men have hidden weapons. You could fight your way out, but you will be badly outnumbered, and your captors will come after you.

What do you do?

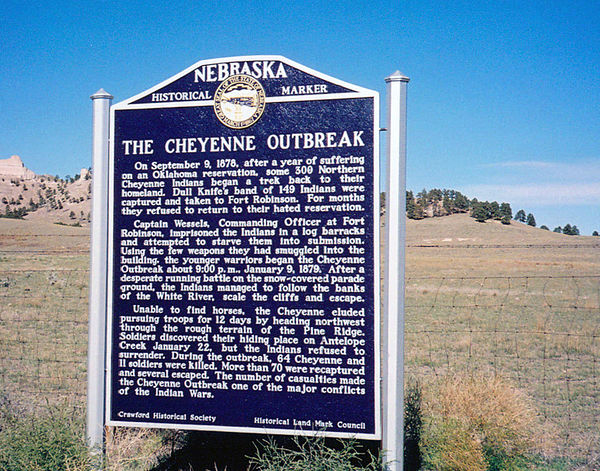

People really faced this choice at Fort Robinson 140 years ago this January 9. It’s known variously as the Cheyenne Outbreak, the Fort Robinson Massacre, and several other names (more about that below).

Last October we dedicated a new historical marker about events leading up to the tragedy of January 9. Historical markers tell the story of this homeward journey. They also raise questions about the names we give to events and how we remember them.

Here’s the story in brief:

The Northern Cheyenne were removed from their homeland to an Indian Territory (Oklahoma) reservation in 1877.

“These encampments in Oklahoma were concentration camps, where there was no food, no lodging, no medicine and diseases that they had no resistance to,” author Joe Starita told NET News when the new marker was dedicated. After hundreds of deaths, a group of 300 people led by Dull Knife and Little Wolf decided to go home. They set out for the Powder River Country of Montana.

A new historical marker, “Escape of the Northern Cheyenne,” stands along Highway 30 near Ogallala. It marks the place where more than 300 people crossed the South Platte River and Union Pacific Railroad. News of their crossing spread quickly by telegraph. Soldiers arrived by train from Fort Sidney, but the Cheyennes escaped into the Sandhills.

The Cheyennes soon parted ways, with Little Wolf leading one group and Dull Knife leading the other. Little’s Wolf’s people eventually made it home to Montana, but Dull Knife’s people were captured and taken to Fort Robinson.

The people—149 men, women, and children—were confined in a cavalry barracks. At first they were free to leave the building. Dull Knife tried to convince the army to let his people either go to Montana or join Red Cloud’s Lakotas. But officials in Washington insisted that the Cheyennes return to Indian Territory.

Photo: A replica of the 1874 cavalry barracks building stands on the spot of the original building at Fort Robinson. Dull Knife’s people were imprisoned here.

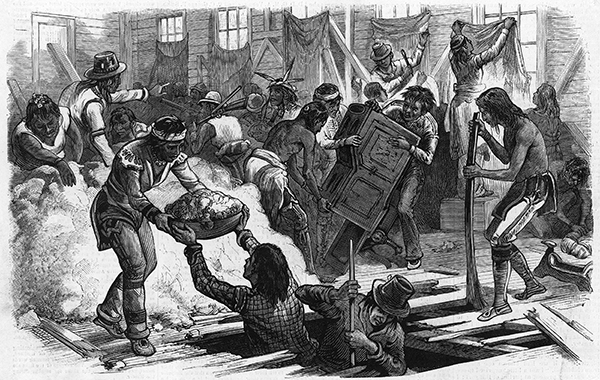

Top photo: Illustration of the breakout from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Feb. 15, 1879.

The Cheyennes refused. To break their will, the fort’s commanding officer ordered them confined to the barracks in late December without food and without wood for heat. On the night of January 9, the Cheyennes broke out of the barracks. Some of the men shot guards with weapons they had hidden earlier, and the people fled the fort. Soldiers hunted them down. When it was over, 64 Cheyennes and 11 soldiers were dead, and most of the remaining Cheyennes were captured.

* * *

This event was long known as the “Cheyenne Outbreak,” but that name is now falling out of favor. “Outbreak” reminds people of a contagious disease. It sounds prejudiced against the Cheyenne, as if they were the problem.

But there’s not yet a consensus on a new name, and not everyone objects to the old one. Northern Cheyenne youth still participate in the annual Fort Robinson Outbreak Spiritual Run, though the term “breakout” is often used both by Native and non-Native historians. The event is also known variously as the Fort Robinson Massacre, the Fort Robinson Tragedy, or the Northern Cheyenne Massacre.

Which name do you choose? Does a new name create confusion when the old one appears in more than a century’s worth of books, articles, and existing historical markers? Event names imply interpretation, but they are also matters of consensus. You can’t just call an event whatever you like and expect people to know what you’re talking about.

Photo: Historical marker at Fort Robinson State Historical Park, Crawford.

We had a decision to make. We needed to connect the new marker’s story to the events of January 9, and we had to do so on an expensive metal sign built to last for many decades.

“Fort Robinson Massacre” seems to be the most common name in new sources. (Among other things, it’s the name of the event’s Wikipedia page, which may be both a cause and a result of that name’s growing popularity.)

We and the marker’s sponsors decided to say that the event is “known as the Cheyenne Outbreak or Fort Robinson Massacre.” The first name links it to more than a century’s worth of references to the “Cheyenne Outbreak” in historical literature. The second is a better description of what happened and seems likely to become standard.

This difference of a few words tells a larger story. It’s not just about what happened in 1878-79. It’s also about what has changed since then.

Consider what else was going on in January 1879. That month a group of Ponca Indians led by Chief Standing Bear fled their Oklahoma reservation for their Nebraska homeland. In the resulting court case, Standing Bear v. Crook, a federal judge ruled for the first time that an Indian was a “person within the meaning of the law” and possessed legal rights.

Today we live in a culture shaped by people like Standing Bear, and by the Northern Cheyenne tribal members who gather at Fort Robinson each January for a ceremony commemorating their ancestors. The events of the past have not changed, but we as a people have changed, and the language we use reflects that.

Photo: Two Northern Cheyenne men at Fort Robinson for a ceremony in January 2018.

—David L. Bristow, Editor

(1/2/2019)