The Ford Conservation Center has been conserving a unique painting on paper by celebrated Nebraska artist Gale D. Jones.

Jones was born in Tilden, NE in 1956 and grew up in Neligh, Nebraska. He received degrees in Fine Art and Art Education from Kearney State College (now the University of Nebraska at Kearney), with a specialization in watercolor. While a student in Kearney, he began exploring techniques that would evolve into his signature style.

As a student, Jones was inspired by pointillism and the natural world. He wanted to explore the ways that colors interact with one another, and to discover how he could breathe additional life into a static painting. He began by developing what he called the “grid technique.” For this technique, he used tape to mask off sections of paper, then completed a watercolor over the lines of tape. After the paint was dry, he removed the tape to expose strips of unpainted paper. He would then place a new layer of tape over the painted sections and complete a second painting in the empty space using a slightly different color palette. This dual-image process added depth, movement, and personality to his works.

Sandhill Cranes, 1978-79. This is an example of Jones’ “grid technique” of painting over taped-off sections of paper.

Jones kept experimenting with other processes that could provide similar results. His second approach was to execute two complete watercolor paintings on separate papers, then to cut one of them into ½” squares and paste them onto the second painting. The result was an alternating checkerboard “mosaic” of the two paintings, which provided additional texture and depth to the completed work. This was a very exacting and time-consuming process, and Jones often told a story about a time when a friend of his opened a door while he was working, causing a draft that sent pieces of his painting fluttering across the room.

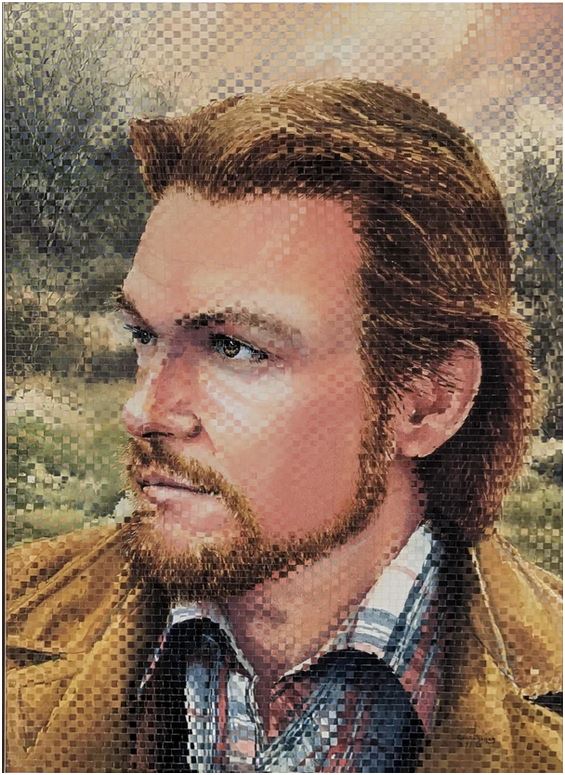

This mishap led to the final iteration of Jones’ technique—executing two separate watercolor paintings, then cutting them both into strips and weaving the strips together. He completed more than 70 of these “woven watercolors” over the course of his career, including at least two during a period of blindness that was caused by illness when Jones was in his late twenties.

An example of Jones’ signature “woven watercolor” technique, I See…A Second Chance is a self-portrait that Jones completed in 1983, shortly after his vision was restored. This particular work is woven from ¼” strips of painted watercolor paper.

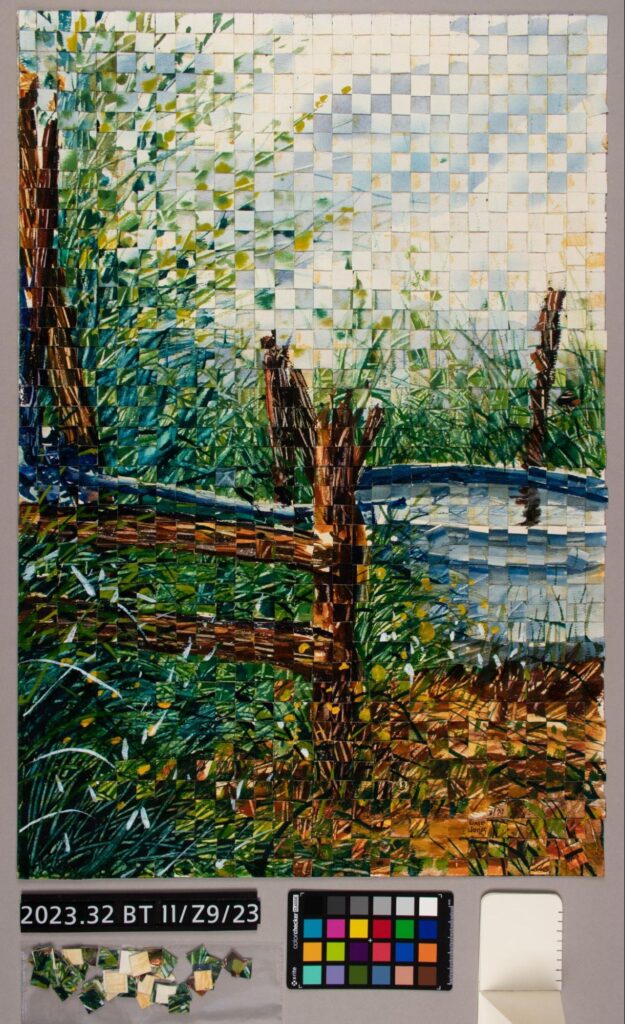

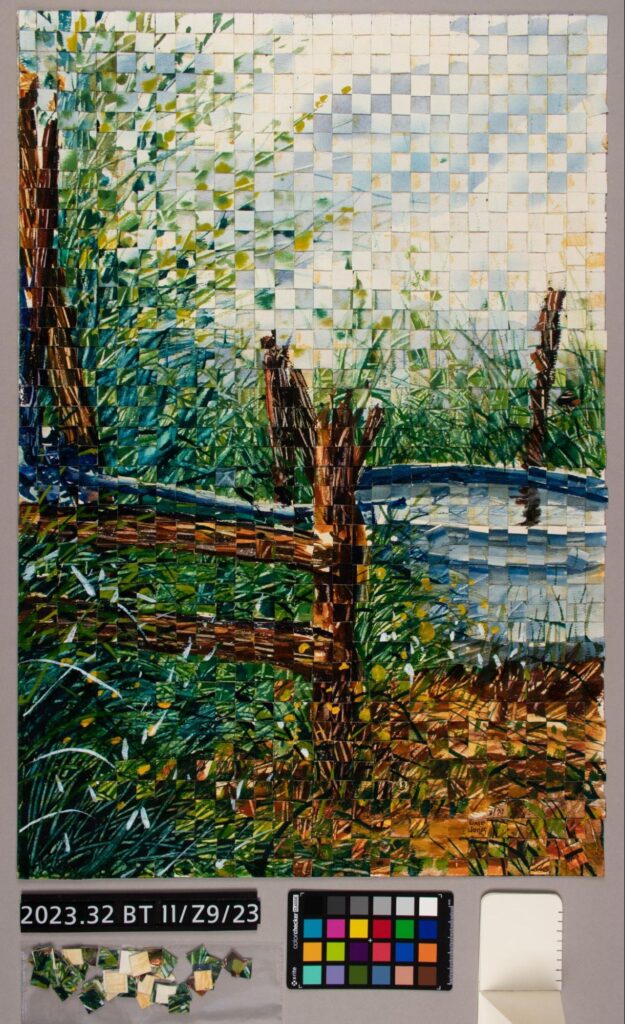

The painting that was brought to the Ford Conservation Center, titled “Otto’s,” was from Jones’ mosaic period, when he glued small painted squares onto a second painting. Over time, the adhesive used to create this mosaic effect started to fail, which resulted in dozens of detached and loose squares. The adhesive had also discolored upon aging, leaving shiny orange residues visible across the painting.

In the before-treatment image above, the darkened adhesive is most visible in the sky in the upper right quadrant.

Under raking light, it is easy to see the three-dimensional mosaic effect. The locations of missing squares are also more visible, particularly in the bottom left corner of the painting.

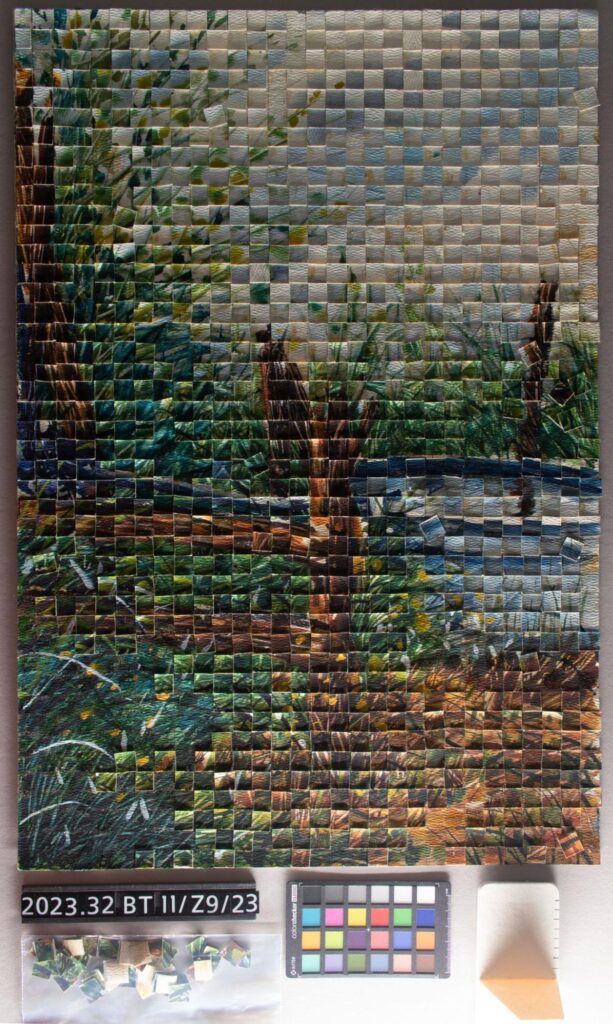

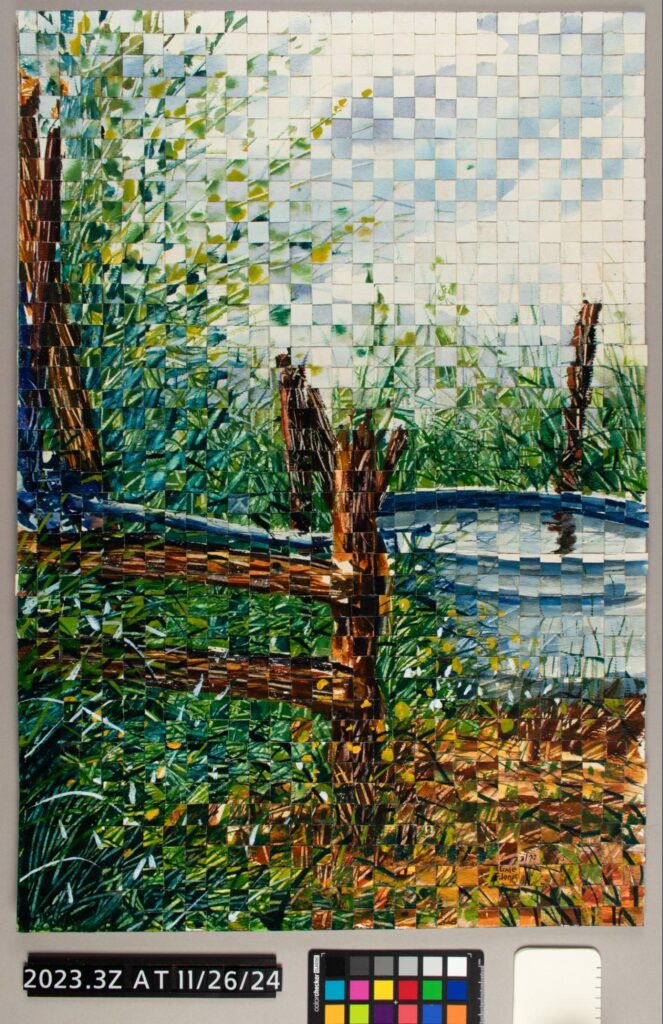

The first step of the treatment was to re-adhere any loose squares that were in danger of detaching from the painting. Saved pieces of the mosaic that had become detached over time were carefully examined to determine their original locations to the extent possible. These pieces were then re-adhered using reversible conservation-grade adhesives.

The next step was to remove as much of the visible yellowing adhesive as possible. Appropriate solvents were chosen through testing and carefully applied to the affected areas to reduce the yellowed residue. This returned the painting closer to its original appearance and will help to improve the overall longevity of the work.

The photos above highlight the efficacy of the adhesive reduction process. In the after photo, the yellow residue has been almost completely removed from the square.

The final step of the treatment was to mount the painting onto a sturdy mat board that provides extra support and rigidity for the painting. This will help reduce the risk of mosaic pieces falling off in the future from handling or flexing the paper.

Left: In the before treatment image, the yellowed adhesive is visible in the lightest areas of the painting.

Right: After treatment, the adhesive residues have been reduced and the detached pieces have been re-adhered.