By David L. Bristow, Editor

Content Warning: This post quotes offensive, racist language and includes a detailed depiction of a murder scene.

Claude and Nellie Nethaway. From Omaha Bee, Nov. 4, 1918, Aug. 28, 1917.

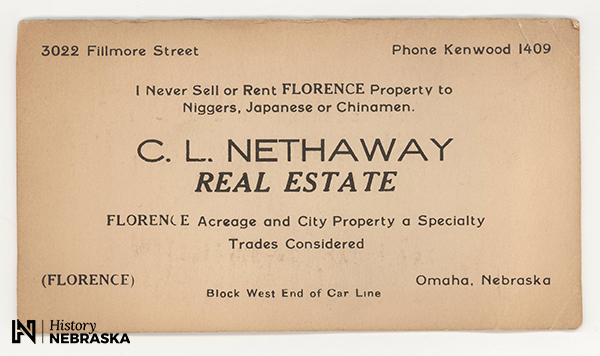

His business card left no doubt where he stood:

Card: History Nebraska 9618-178

This card caught our attention when it was donated to History Nebraska several years ago. It wasn’t news to us that housing discrimination existed in Omaha and its suburbs, but we weren’t used to seeing it advertised so blatantly. That wasn’t the usual Northern style. Who was Claude Nethaway, and what was his story?

Then we learned that in 1917 an African American man had been convicted of brutally murdering Nethaway’s wife. That didn’t make the grieving widower’s racism excusable, but it did make it more understandable.

But the deeper we looked, the weirder things got.

* * *

On the afternoon of August 26, 1917, a frantic Claude Nethaway told his neighbors that his wife, Nellie, had not arrived at a scheduled meeting. He wanted to form a search party to look for her along nearby railroad tracks.

If that sounded strange, Claude had an explanation. His real estate office was near 30th Street in Florence. The couple’s 40-acre farm was west of 60th Street northwest of town. It was a bit of a roundabout drive home, so when they planned to do some shopping, they arranged to meet at a place called Briggs’ Crossing a half-mile south of the farm. Claude would drive there from his office. Nellie would walk there along the tracks. The 40-year-old wife of a businessman planned to begin a shopping trip into the city by walking a half-mile along railroad tracks on a hot August afternoon.

But she never arrived. The searchers explored the right-of-way until they reached a deep, steep-sided cut. Claude shouted from the top of the embankment.

Nellie’s body lay in the tall grass about 40 feet from the tracks. Her hands were bound with a strip of her own clothing, and her throat was slashed nearly ear to ear. A large hunting knife lay nearby.[1]

Newly annexed by Omaha, Florence was now under the jurisdiction of the Omaha Police Department. OPD almost immediately had a suspect. A black man had been seen in the neighborhood earlier that afternoon. A man matching his description was soon arrested in Blair, and admitted having hopped a train in Florence.

His name was Charles Smith. Newspapers described him as a “tramp.” The 32-year-old Mississippian had done some time in a Kansas prison for burglary.[2] To the white public he seemed to be just the kind of man the Omaha World-Herald was talking about when it complained of “the northward movement of the most ignorant, shiftless, and dangerous element of the black population of the south.”[3]

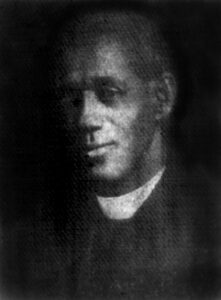

Omaha’s African American population more than doubled between 1910 and 1920, part of what historians call the “Great Migration” of Southern black workers to Northern cities. Responding to the World-Herald’s editorial, the African American Omaha Monitor defended the “industrious” migrants, complained of “dangerously sensational headlines” in the Omaha Bee, and raised money for Smith’s legal defense, so that—guilty or innocent—he might at least receive a fair trial.[4]

* * *

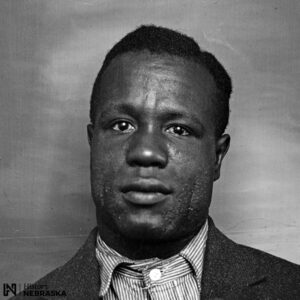

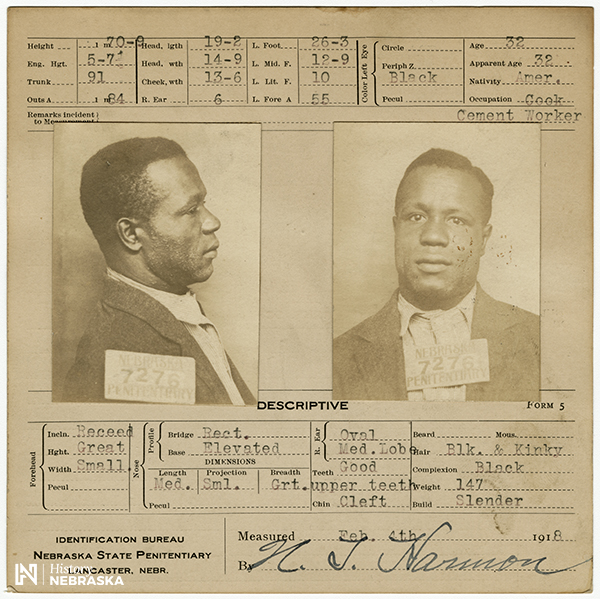

Photo: Charles Smith, 1918. History Nebraska RG2418-7276a

But days passed without Smith being formally charged. The police simultaneously boasted to the press of their certainty of his guilt, while quietly acknowledging that they had no evidence against him other than his proximity to the crime. Day after day, Smith maintained his innocence and failed to crack under interrogation while being held in solitary confinement at the Douglas County Courthouse.

A local probation officer named Andreesen, known for his “wide experience with criminals, murderers and degenerates,” interviewed Smith and declared him innocent. Andreesen used a common racist slur to describe the suspect: “He’s just a plain southern shine who was unlucky enough to be in the vicinity.”[5]

“I’d stake my reputation Smith never murdered that woman,” Andreesen added five days later after further interviews.[6]

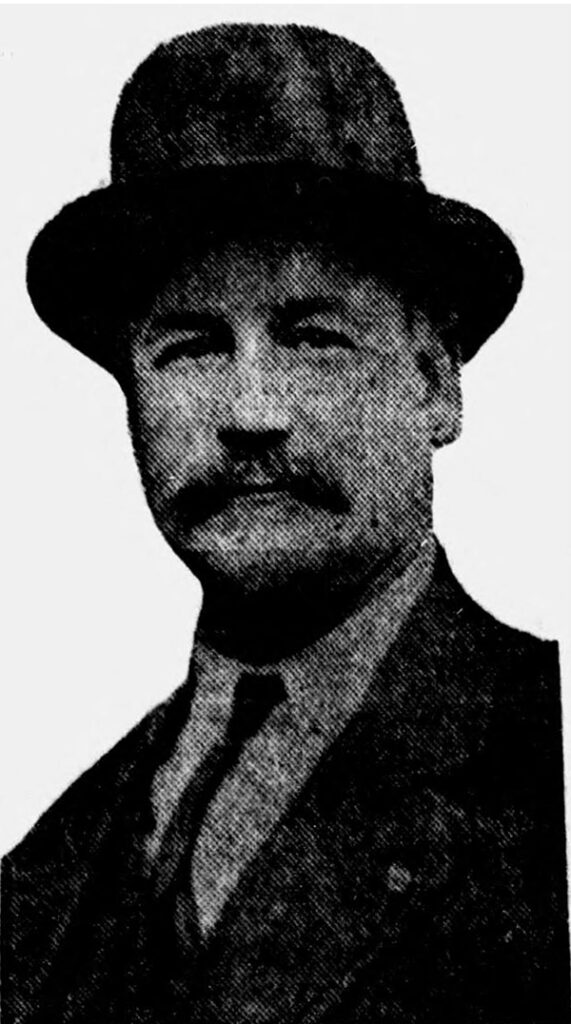

Andreesen wasn’t the only skeptic. Douglas County Sheriff Mike Clark and other county officials showed little regard for OPD’s detective work and believed Smith was innocent. County deputies found no evidence that Mrs. Nethaway had been dragged from the tracks to where her body was found atop the embankment, and it was difficult to imagine how even a large man (Smith weighed 147 pounds) could carry her up that steep and deeply gullied slope.

So it appeared that Mrs. Nethaway had walked voluntarily to that spot by another route, but why? Further, she had been neither raped nor robbed (her necklace was on the ground). The big hunting knife did not even appear to be the murder weapon—the fatal neck wound looked like it was made by a smaller and sharper blade. A razor was found buried nearby. A piece of women’s underwear discovered at the scene didn’t match the other clothing and appeared to have been cut with scissors. In all, it looked like someone had planted fake evidence.[7]

At first, OPD doubled down on Smith’s guilt, floating the hypothesis that Smith suffered from amnesia and thus could offer sincere denials of the crime he didn’t remember committing. As for the big knife, police said it was clearly Smith’s attempt to mislead investigators.[8] But even the police were not unanimous: both a detective and a captain told the press they thought Smith was innocent.[9]

But it would be up to a coroner’s jury to make a recommendation.

Photo: Douglas County Sheriff Mike Clark. From Omaha Bee, June 28, 1918.

* * *

Claude Nethaway accompanied the members of the coroner’s jury as they struggled up the steep slope to the murder site. There he threw himself facedown for 15 minutes, clutching the blood-matted grass while screaming, moaning, praying, cursing, and “babbling incoherently.” At a preliminary court hearing he spoke so rapidly that jurors could not understand him.[10]

Nethaway acknowledged that he was an excitable man, describing himself in real estate ads as a “local live wire.” A neighbor said he’d heard Claude and Nellie arguing loudly at times, and that Claude sometimes cursed his wife for minor offenses such as not opening a gate for him quickly enough.[11]

Another Nethaway family matter appeared briefly in the World-Herald on September 4. Someone had remembered that Claude wasn’t the first of the Nethaway boys to make headlines for losing a wife.

* * *

Back in 1907, Mary Nethaway—wife of Claude’s older brother, Valley—had had enough. On December 5 she boarded a train in Norfolk bound for Madison. She was going to the county courthouse to file for divorce.

The train had just begun to pull out of the depot when Valley swung aboard, shotgun in hand.

“Prepare to die,” he told his wife before firing both barrels into her head.

Valley then jumped from the car and walked to a grain elevator across the street. He phoned his mother and then shot himself in the head with a revolver.[12]

* * *

The coroner’s jury concluded that Nellie Nethaway was murdered by an unknown person, but recommended that Smith be held for further investigation. Smith was formally charged with murder three days later, despite there being no new evidence and despite the prosecution’s public doubts about obtaining a conviction.

But not everyone had doubts. County officials concealed the time of the arraignment for fear of a lynch mob. Somehow the courtroom was packed anyway. And to anyone who would listen, Nethaway proclaimed his certainty that Smith was the murderer.[13]

Editor J.A. Williams of The Monitor protested the weakness of the case and lamented that “while a white man’s crime is attributed to him alone and is regarded as the act of an individual, the crime of a black man seems to be regarded as a corporate act and a reflection upon the race to which he chances to belong.”[14]

* * *

Photo: Rev. John Albert Williams was president of the local NAACP and editor of The Monitor. He helped raised funds for Smith’s defense. From the Monitor, June 9, 1922.

The trial opened on November 12 after some difficulty finding jurors not already convinced of Smith’s guilt.[15] The prosecution’s case centered on Nellie’s blood-stained clothing and Claude’s emotional testimony. (“‘My God!’ I yelled, ‘I’ve found her!’” he said, describing his discovery of his wife’s body with a voice that “froze the blood in the veins of his listeners… with the unexpectedness of his weird cry.”)[16]

In its initial vote, the jury stood nine-to-three in favor of acquittal, and remained so after 42 hours of deliberation. The judge dismissed the jury and ordered a new trial.

“The lack of evidence upon which the prosecution has based its case is almost farcical,” the Monitor complained.[17] But in February 1918 a second jury voted to convict on essentially the same evidence. Smith was sentenced to life in prison.[18]

Photo: History Nebraska RG2418-7276

* * *

Trial transcripts are not available, and only the Monitor reported certain details, such as testimony that it was only a four-to-five-minute drive from Nethaway’s office to his home, raising the question of why Nellie would walk a half-mile on railroad tracks to meet him. Or a neighbor’s testimony that she had seen Claude earlier that day wearing dark clothes, and again in the afternoon wearing light-colored clothes.[19] Several of Nethaway’s friends acknowledged later that after the murder they heard as many local people speaking against Nethaway as for him, but that Smith’s conviction greatly improved Nethaway’s reputation in Florence.[20]

Nethaway quickly embraced open racism as a marketing strategy, proclaiming his whites-only views on letterhead, business cards, and newspaper ads. In the fall of 1918 he ran an independent campaign as the “White Man’s Friend” against Sheriff Mike Clark, whom he resented for his testimony in Smith’s defense. Nethaway promised that his first official act as sheriff would be to fire the jail’s black elevator operator.[21] He received fewer than 300 votes.[22]

* * *

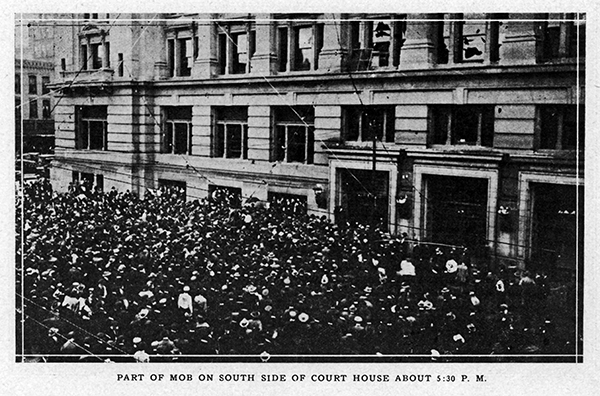

Nethaway was back in the news following the September 28, 1919, lynching of Will Brown at the Douglas County Courthouse. Brown had been accused of raping a white woman. A mob of thousands stormed the courthouse (which also housed the jail on its top floor), set the building on fire, lynched Brown and burned his body, and even tried to lynch the mayor when he intervened.

Nethaway was arrested the next day, charged with conspiracy to murder and unlawful assembly. Specifically, he was accused of taking a prominent role in urging the mob to “get the nigger and lynch him,” and of boasting afterward of having fired shots into Brown’s body.

“Well they can’t convict anyone anyway,” Nethaway reportedly told a friend who had urged him to keep quiet.[23]

But Nethaway spent a few months in jail awaiting trial. And when he tried to incite the other inmates, Sheriff Clark ordered him placed in solitary confinement—ironically, in the same cell that Charles Smith had occupied two years earlier.[24]

“Get me out of this hell-hole,” Nethaway wrote to the county attorney. “I am in here with all kind of persons. It is hell.”[25]

But that was all the time Claude Nethaway would ever serve. Despite a dozen witnesses testifying against him, the jury was unable to reach a verdict. Unable to secure convictions, the county attorney eventually cleared the dockets of cases related to the Will Brown lynching.[26]

Photo: From the booklet Omaha’s Riot in Story and Picture (Omaha: Educational Publishing Company, 1919)

* * *

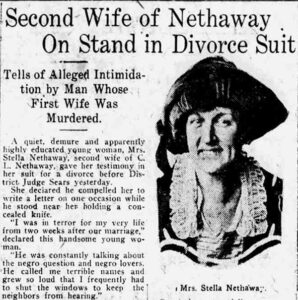

Nethaway was free, but his life was far from tranquil. He had remarried in 1918, and in 1920 his second wife, Stella, filed for divorce. She said her husband was excitable, nervous, and spent most of his time at home talking about the “negro question” and railing against “negro lovers.”[27]

“I was in terror for my very life from two weeks after our marriage,” Stella said. On one occasion, she said, Claude forced her to write a letter while standing near her with a knife. She showed the court letters Claude had written, many of them incoherent.[28]

Stella won her divorce and alimony and returned home to Chicago, but Claude wasn’t done with her. He got her fired from her job by sending postcards to her employer accusing her of immoral behavior. He also sent Stella postcards that got him fined for sending “obscene matter” through the mail.[29]

Through all this, Nethway’s real estate business went on as before, at least to judge by his newspaper ads. He eventually married a third time—peacefully as far as we know—and continued to run unsuccessfully for public office and write letters to the editor on a variety of political topics. He was known in the press as an “eccentric Florence real estate man” and received a pleasant obituary at the time of his death in 1937.[30]

* * *

Photo: Omaha Bee, Sep. 30, 1920.

In many ways Claude Nethaway was not typical of his time and place, but he shows the limits of what the public was willing to tolerate from a white businessman.

But did he murder his wife? All we can say is that the case against him looks stronger than the one that convicted Charles Smith. And yet no one seems to have investigated that possibility at the time.

If Nethaway did it, he was no criminal mastermind. His alibi was weak, the planted evidence was amateurish, and his subsequent behavior showed him to be a jealous, explosive, and violent man.

Nethaway may have hoped to cast suspicion on the hobos often found along railroad tracks, but it seems unlikely that he plotted specifically against Smith, whose timely presence he couldn’t have predicted. Smith’s appearance that day may have been Nethaway’s lucky break.

After that, the chain of events played out with tragic stupidity. Smith was suspected because of his presence, and presumed guilty because of his race. The police had a weak case but dug in their heels in response to criticism from the county sheriff, their institutional rival. The prosecution seemed eager to satisfy the public with a conviction—any conviction—and in the courtroom relied mostly on gore and outrage.

Once Smith was convicted, it didn’t matter what Nethaway did next. No one would revisit the case. As with the trials following the lynching of Will Brown, most of the public simply wanted to drop the matter and move on. As for Smith himself, he died at the Nebraska State Penitentiary on June 12, 1918, only four months after his arrival. Newspapers did not report it, and his prison record does not include cause of death.[31]

You may also be interested in:

- “‘Lest we forget’: The lynching of Will Brown, Omaha’s 1919 race riot.”

- Laurel Sariscsany, “‘They can’t convict anyone anyway’: The trials of the Omaha lynching and riot of 1919.” This article appears exclusively in the Fall 2019 issue of Nebraska History Magazine, received by History Nebraska members.

[1] Omaha Bee, Aug. 27, Sep. 2, Nov. 14, 1917; Omaha World-Herald (OWH), Aug. 27, 1917.

[2] Bee, Aug. 31, 1917.

[3] OWH, Aug. 28, 1917.

[4] Omaha Monitor, Sep. 1, 1917.

[5] Bee, Aug. 29, 1917.

[6] Bee, Sep. 4, 1917.

[7] Bee, Sep. 1, 2, 4, 1917, Nov. 14, 1917; OWH, Sep. 3, 4, 1917.

[8] Bee, Aug. 31, 1917; OWH, Sep. 3, 1917.

[9] OWH, Sep. 4, 1917.

[10] Bee, Sep. 1, 2, 1917.

[11] Bee, Oct. 4, 1914.

[12] Norfolk Weekly News-Journal, Dec. 6, 1907.

[13] OWH, Sep. 5, 6, 1917; Bee, Sep. 8, 1917.

[14] Monitor, Sep. 8, 1917.

[15] Bee, Nov. 13, 1917.

[16] Bee, Nov. 14, 1917.

[17] Monitor, Nov. 24, 1917. See also Bee, Jan. 23, 1918.

[18] Bee, Jan. 27, 1918, Feb. 5, 1918.

[19] Monitor, Nov. 24, 1917.

[20] Bee, Jan. 8, 1920.

[21] Laurel Sariscsany, “‘They Can’t Convict Anyone Anyway,’: The Trials of the Omaha Lynching and Riot of 1919,” Nebraska History 100 (Fall 2019): 157.

[22] Bee, Nov. 7, 1918.

[23] Sariscsany, 158.

[24] Bee, Oct. 5, 1919.

[25] Bee, Oct. 4, 1919.

[26] Bee, June 16, 1921.

[27] Bee, Feb. 19, 1910.

[28] Bee, Sep. 30, 1920.

[29] OWH, Nov. 19, 1920.

[30] OWH, Mar. 20, 1937.

[31] Nebraska Prison Records 1870-1990 Index, https://history.nebraska.gov/collections/nebraska-prisoner-records-database