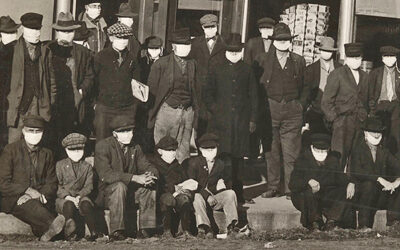

Photo: “Woman’s Rights #2,” detail of 1902 stereograph image by Omaha and Lincoln photographer J.M. Calhoun. History Nebraska RG3279-2

By David L. Bristow, Editor

Can you imagine living in a country where women are not allowed to vote? And what if most men and women thought it should stay that way?

What would you say to change peoples’ minds? And what might they say in reply?

History Nebraska is commemorating the centennial of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution, which extended voting rights to women in 1920. Nebraska ratified the amendment on August 2, 1919. A new book and new exhibit at the Nebraska History Museum tell the story of the women’s suffrage movement in Nebraska.

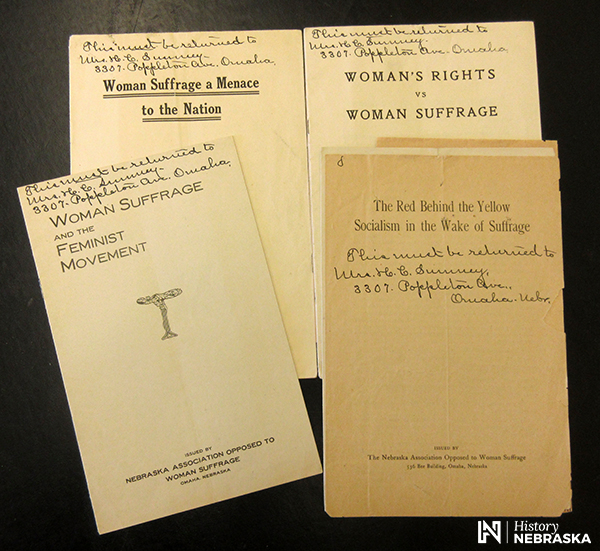

Anti-suffrage viewpoints are an important part of the story. To understand what suffragists were up against—and why it took them so long to win—it helps to know what their opponents were thinking.

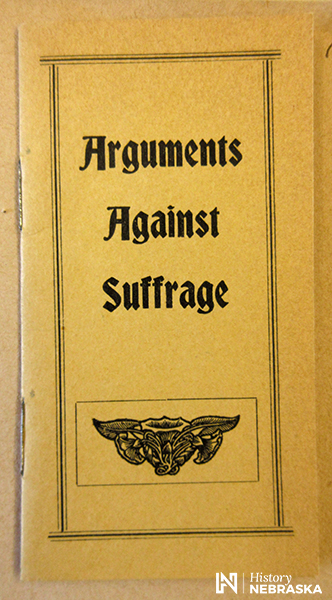

History Nebraska has many documents from the period, including pamphlets published by local anti-suffrage groups in the 1910s. I’ve posted PDFs of some of them, linked below.

The pamphlets are brief, pointed, and written to persuade a popular audience. To a modern reader their arguments sound silly, but these yellowed pages are a window into the minds of mainstream Nebraskans a century ago, as they defended traditional views that were being challenged. Ask questions as you read their words. What do the writers assume? What do they value? What do they fear?

Woman Suffrage a Menace to the Nation, by Mrs. Helen Arion Lewis, was written by an ex-suffragist living in Omaha. Lewis warns of “the degradation of womanhood… when she becomes embroiled in political intrigue.” She writes that Mormon women voters in Salt Lake City are tolerant of polygamy, while in Denver the votes of “scarlet women” (prostitutes) empower a corrupt city government.

Overall, Lewis says “90 percent of the women either stay at home, vote as directed by their husbands, or vote under a wicked influence… I am firmly convinced that woman can exercise an even greater influence along educational lines without the ballot than she can with it.”

“I maintain that the very womanhood of America is threatened, not by the simple act of placing the ballot in the box on election day, but by participation in campaign activities, and the intimate and unconventional contact that would serve to erase the tradition of women’s dependency—the fundamental factor in all the world’s history that has served most to nourish the love and respect of man for woman.”

The Red Behind the Yellow: Socialism in the Wake of Suffrage argues that because socialists are among the supporters of women’s suffrage, women’s suffrage will therefore lead to socialism. Let women vote and they will abolish private property, loosen divorce laws, get jobs, and put their children in government-funded daycare.

Yellow was known as the color of suffrage—suffragists commonly wore yellow sashes and waved yellow banners, but this author warns that we are “threatened by a red peril in a yellow cloak.”

In the same way that The Red Behind the Yellow links suffrage to socialism, Woman Suffrage and the Feminist Movement links suffrage to feminism, which it defines as support of: “free love” (sex outside marriage); “voluntary motherhood” (married and unmarried women choosing when and whether to have children); married women keeping their last names; equal division of housework; and opposition to biblical teaching about gender roles.

Women were deeply involved in the leadership of the anti-suffrage movement, but the Nebraska Men’s Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage Manifesto was an exclusively male publication addressed “To the Electors of the State of Nebraska.”

“We yield to none in our admiration, veneration and respect for woman,” the Manifesto begins. “We recognize in her admirable and adorable qualities and sweet and noble influences which make for the betterment of mankind and the advancement of civilization.”

Such flattery reflected traditional views of gender. Men were seen as naturally aggressive and competitive, providing society’s drive and leadership. Women were seen as a nurturing and civilizing influence, providing refinement and moral elevation. The Manifesto praised women’s contributions to education, charity, and benevolent work, while calling on them to stay out of politics. (Anti-suffragist women such as Mrs. Helen Arion Lewis agreed, fearing women would lose their moral influence by gaining voting rights.)

Voting, the Manifesto argues, is not a natural right but a privilege—a privilege that the nation’s wise founders chose not to grant to women. Then the argument turns racist: “It is well known that all the Latin races, by reason of their temperamental conditions are excitable and emotional.” The author points to the frequent revolutions and turmoil in Latin America as evidence that “excitable and emotional” women cannot be responsible voters.

“This country has already extended suffrage beyond reasonable bounds. Instead of enlarging it, there are strong reasons why it should be curtailed.” The Manifesto calls for “some reasonable standard of fitness for the ballot.”

In other words, the organization’s opposition to women’s suffrage reflected their broader desire to restrict voting to white men of a certain social class.

By the time these pamphlets were printed, these arguments were already losing force as more and more Americans embraced a broader view of women’s capabilities. Perhaps the most eloquent response from the Nebraska Woman Suffrage Association came in a pamphlet of their own:

Here’s the inside:

Like the other pamphlets linked below, this one is stapled into a large scrapbook assembled by suffragist Grace Richardson and donated to History Nebraska in the 1950s (Nebraska Woman Suffrage Association Collection, RG1073.AM.)

See also: “Ten Reasons Why Women Don’t Want the Right to Vote”; and many more articles, blog posts, and other “Women’s History Month Resources.”