Official portrait of Judge Joseph William Woodrough

Official portrait of Judge Joseph William Woodrough

In 1897, a twenty-four-year-old attorney came to Omaha to start his career in earnest. He lacked a law degree—or any degree for that matter—but had been admitted to the profession on the basis of having read a few legal treatises and because some prominent citizens vouched for his character. His story is told in the Summer 2016 issue of Nebraska History in the article “The Wayfaring Judge: Woodrough and Organized Crime in the U.S. District Court” by Nick Batter, who is an attorney in Omaha. As the 19th century came to a close, the attorney—Joseph William Woodrough—had grown to become one of the “leading legal lights of the State.” By pure coincidence, just as Woodrough was arriving in Omaha, the city’s four biggest crime bosses were leaving in a hurry, under mysterious circumstances. Their power vacuum would be filled almost instantly by another recent arrival, Tom Dennison, whose career up until that point had consisted almost exclusively of gambling and theft across a variety of frontier towns. By the turn of the century, the gambler was king of Omaha’s underworld, having consolidated power by leveraging corrupt police officials to rout his rivals. Untouched by Denison’s corrupting influences, Woodrough formed a philosophy and lifestyle that would undergird the rest of his life. He complained: “We have elaborate systems of courts in this state that cost the people millions of annual outlay, and they take five years to decide a dispute about a bill of goods. We have legislatures that often follow dark and devious ways, and bosses in every city that can deliver votes with unholy certainty.” Just as previous generations had fought against the evils of “kingship” and “slavery,” he saw his generation as needing soldiers, too. This new fight “will take the brain and courage of men to fire their hearts and spur them on to heroism as grand as the race has seen.” He called on his peers to reject corruption, bossism, and bureaucracy, and referred to men who used their talents merely for wealth as “vulgar.” His philosophy permeated more than his rhetoric; Woodrough adopted a strict personal regimen. A colleague on the federal bench, Richard Robinson, would later remember him as “Spartan in his tastes and in the way he lived. He shunned luxury hotels, he spent little time in clubs . . . he disliked ostentation or pomposity in any form [and] believed in physical fitness.” Woodrough usually marched the ten miles from his home to the courthouse and, when hearing cases in Lincoln or elsewhere in the state, was known to travel the distance on foot.

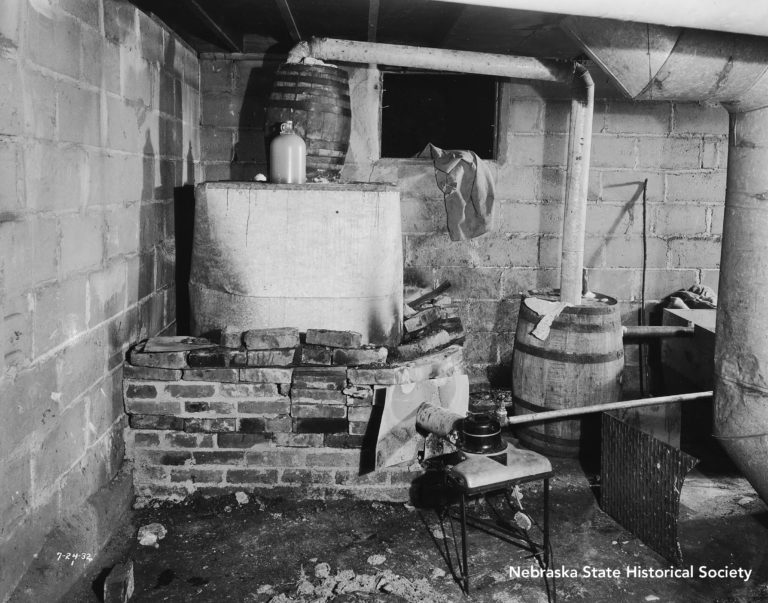

A basement still found in a Lincoln home in 1932.

A basement still found in a Lincoln home in 1932.

Justice Blackmun would later recollect:“woe unto the law clerk . . . not able to keep up with him.” He prescribed his clerks with outside reading on a wide variety of topics. He would regularly order the “whole platoon” to report to his house, where he would offer “good, if simple food” before showing them “a tree to chop down, or a fence to paint, or some other household chore requiring strong young backs.” However, despite Woodrough’s simple tastes, serious philosophy, and habit of walking tremendous distances on foot, he was not a severe figure. Rather, above all else, former friends and clerks remembered his friendliness and sense of humor. “He was a peach, just a great guy. Didn’t go to law school. Didn’t write any articles. Just a real human being.” Throughout his career, without ever seeming to compromise his values or strict self-discipline, he managed to maintain a boyish demeanor and optimism. In his chambers, which were often “full of laughter,” he would use stacks of legal tomes to perform afternoon calisthenics, or as an improvised bed for a mid-day nap. In 1918, as fledgling Allied air forces were bombing Cologne, Woodrough was unexpectedly absent from court, missing the plea hearing of a hotel clerk facing charges of selling whiskey to soldiers. The judge, apparently more concerned with what soldiers were eating, was discovered at home, “doing his bit” by tilling up his lawn to make a victory garden. He even registered for the draft, despite being past the cut-off age. Unsurprisingly, the draft board’s physical examiners found him perfectly fit to fight.

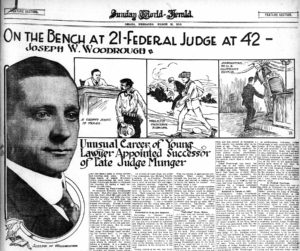

Omaha World Herald, March 26, 1916

Omaha World Herald, March 26, 1916

Woodrough’s good humor, coupled with his distaste for the exclusive social clubs where his colleagues spent much of their free time, allowed the judge to remain grounded and empathetic to ordinary, working-class Nebraskans. Chief Judge Robert Van Pelt would remember him as “the most human judge the District Court of Nebraska has ever had.”24 An (apparently) amateur poet would go further, penning: “He sits upon that bench, just like you and me / And the office does not swell his head / in the slightest degree / For he belongs to the people they call the / Common Herd/ For degrees of self-importance to him they / are absurd / He cares for no one in so far as their success / For he treats the wealthy just like the widow/ in distress / And while upon the bench he is patient all / the while / And carries with him a nice and lovely smile.” He seemed to charm many of those who entered his court. On one occasion, despite receiving a $50 fine from Woodrough, a repentant haberdasher blurted out: “Judge, any time you want your hats cleaned or reblocked it won’t cost you a cent.” The day prior, an apropos editorial in the World-Herald had quipped: “It makes us almost sad that we can’t stand up before Judge Woodrough to be sentenced.” Woodrough’s ascension to the bench would also coincide with a reform movement sweeping the state. Nebraska amended its state constitution to prohibit alcohol in 1917. Those in Omaha frustrated at rampant corruption orchestrated by underworld boss Dennison “argued strongly and persuasively about the need for cleaning and change.” Woodrough was ready for the challenge. Does Woodrough beat Crime Boss Tom Dennison? Do Omaha’s bootleggers and corrupt prohibition agents get reformed? Does Woodrough ever get a bike so he doesn’t have to walk so much?