Frank Shoemaker ranks among important early Nebraskans who applied their interest in nature to learning more about the state and its environmental history. As an amateur naturalist and an expert photographer, Shoemaker focused his life’s work on investigating, observing, and recording birds, landscapes, beetles, and all types of natural flora and fauna. His work focused particularly on Nebraska landscapes in the Panhandle, the Sandhills, and in the once-rural areas of the Lincoln and Omaha metropolitan regions.

Frank Shoemaker ranks among important early Nebraskans who applied their interest in nature to learning more about the state and its environmental history. As an amateur naturalist and an expert photographer, Shoemaker focused his life’s work on investigating, observing, and recording birds, landscapes, beetles, and all types of natural flora and fauna. His work focused particularly on Nebraska landscapes in the Panhandle, the Sandhills, and in the once-rural areas of the Lincoln and Omaha metropolitan regions.

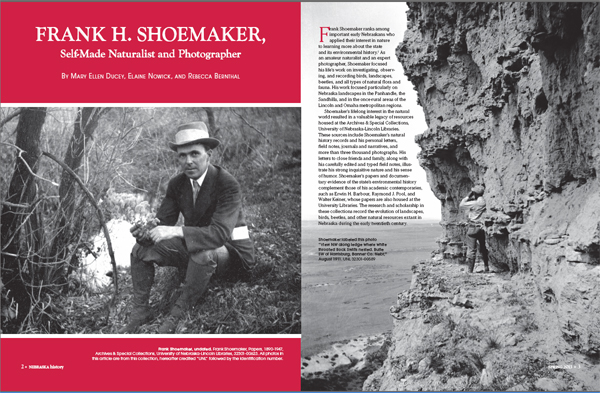

Shoemaker’s lifelong interest in the natural world resulted in a valuable legacy of resources housed at the Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries. These sources include Shoemaker’s natural history records and his personal letters, field notes, journals and narratives, and more than three thousand photographs. His letters to close friends and family, along with his carefully edited and typed field notes, illustrate his strong inquisitive nature and his sense of humor. Shoemaker’s papers and documentary evidence of the state’s environmental history complement those of his academic contemporaries, such as Erwin H. Barbour, Raymond J. Pool, and Walter Keiner, whose papers are also housed at the University Libraries. The research and scholarship in these collections record the evolution of landscapes, birds, beetles, and other natural resources extant in Nebraska during the early twentieth century.

Frank Henry Shoemaker was born on April 2, 1875, in DeWitt, Clinton County, Iowa. His parents were Samuel Henry (S. H.) and Rette F. Ferre Shoemaker. He had one sister, Jessie, seven years his senior. S.H. Shoemaker supported his family as editor of various newspapers in Iowa, first the DeWitt Observer, 1862 to 1888, the Cedar Rapids Gazette, 1888-1890, and last as editor of the Chronicle in Hampton, Franklin County, Iowa.

As a young man, Shoemaker worked for his father and consequently missed his final year in high school. He wrote: “I became convinced that it was my duty to give it up and assist in the publication of the newspaper, as my father’s health was at that time very poor. . . . I pursued my various studies during the evenings, practically covering the twelfth grade work and going farther in certain of the more practical branches.” Efforts to expand his knowledge despite a lack of formal education proved characteristic of Shoemaker’s entire life, supported by his curiosity and his interest in all things related to natural history studies.

Bird study first dominated Shoemaker’s interests and inspired him to devote much of his spare time as a young man to expanding his knowledge of species and habitats. Shoemaker collected bird nests and eggs and documented his findings and his outdoor adventures in field notes. He recorded notes on birds and their behaviors following “tramps” into the woods and fields around his home, documenting the information he discovered about Franklin County, Iowa. Early on he attended lectures of professional ornithologists, such as Herbert Osborn from the Iowa Agricultural College (now Iowa State University), who advised Shoemaker to collect government bulletins to assist his bird studies. Taking this advice, Shoemaker wrote letters to the United States Department of Agriculture requesting publications on bird species. He sought assistance from the Smithsonian Institution “for collecting and preserving natural history material.” These government publications were the foundation for Shoemaker’s studies in ornithology.

At age fifteen, Shoemaker’s field notes indicate that his focus turned to observation rather than collecting. Describing flickers in his front yard Shoemaker noted that the birds “were boring in the ground with their bills, though with what object I could not surmise. I watched them for some time from my room, and noticed the exact position in which they were working that I might examine after the birds had departed. Upon examination I found that they had been engaged in boring into the honey-combed ground occupied by ants’ nests, eating the insects or their larvae, or both. This is a thing I have never before noticed, but the manner in which they conducted themselves showed that it was no new business to them.” While Shoemaker noted that it was sometimes necessary to kill specimens for study, he acknowledged the greater value of research in natural settings. Reviewing his lists for Franklin County he wrote: “the other evening I found I had 104 varieties catalogued: this species makes the 105th on my list. I cannot help being impressed with how infinitely better it is to thus study bird life than to murder and destroy to further the cause of ornithology.”

In Shoemaker’s early records two statements illustrate his shifting views on collecting and observation. In an entry in his field notes on May 14, 1893, Shoemaker “concluded to spend part of today in the woods, not as a collector but as a naturalist, confining myself to observation out of respect for the day.” Shoemaker’s decision on that day perhaps initiated the change that became permanent over the course of his life—a dedication to observing nature in the forms that most interested him and recording it through documents and photographs. The publication of his records, in an 1896 pamphlet titled A Partial List of the Birds of Franklin County, Iowa, provides a second view on bird studies. In the introduction Shoemaker wrote: “other matters have so occupied my time that no opportunity has been given for systematic study in this branch. . . . This list is the result of observations made at odd times; a method not at all conducive to the best results.” Throughout his life, circumstances or practical needs left Shoemaker at odds with his desire to study nature in a professional scientific manner.

The entire essay appears in the Spring 2013 issue.