While many history textbook authors have erased humor from history, primary sources reveal that jokes and hardships together make up an important part of the past. Our newest book, From Our Special Correspondent: Dispatches from the 1875 Black Hills Council at Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska, edited by James E. Potter, is made up of primary newspaper articles that detail the events of this council.

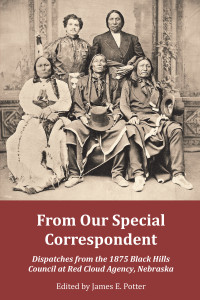

From Our Special Correspondent: Dispatches from the 1875 Black Hills Council at Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska, edited by James E. Potter

From Our Special Correspondent: Dispatches from the 1875 Black Hills Council at Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska, edited by James E. Potter

While discussing such sober things as land deals and the possible extinction of the American Indian, the white and Indian participants often found some sort of comic relief. The so-called “Grand Council” was an attempt by the U.S. government to convince the Lakota people to cede ownership of the Black Hills, then a part of the Great Sioux Reservation, so white settlers could mine the gold in the region. The talks had lasting effects on Indian-white relations and were among the largest gatherings of Indians in American history. Both Indians and whites used humor, and their delivery varied from sarcasm, to dark humor, to pranks. Making connections to the past is easier when one realizes that our ancestors had senses of humor. For example, one thing that hasn’t changed is making disparaging remarks about political figures. After he heard about an expedition going to the Bad Lands in Dakota Territory to search for fossils, one man said dryly, “Well they needn’t go so far in search of fossils for they can find what they want nearer home; let them just gather up the members of this Indian commission.” The newspaper correspondent who recorded the remark added a bit of his own dry humor, writing, “And I blush for my race when I say that to this heartless and irreverent remark there was not a word of condemnation.” The Indian leaders were constantly making wry observations, and these letters preserve only the comments that the newspapermen were smart enough to catch. The total amount of jokes at the whites’ expense probably wouldn’t fit into a book. When the correspondents arrived at Red Cloud Agency, “…an Indian in full dress stalked into the room robed in an air of importance and a coarse blanket, bearing a good sized hatchet on his left arm.” This was Red Dog, who often served as Chief Red Cloud’s spokesman. One of the commissioners asked an interpreter to say “We are glad to see him.” Red Dog replied, “It ought to give anybody pleasure to meet a wise man.” Since he had a hatchet on his arm (and a good-sized one, as if there’s such a thing as a “bad-sized” hatchet), it’s doubtful anyone wanted to argue with him.

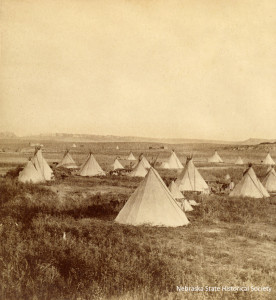

Red Cloud Agency in 1876.

Red Cloud Agency in 1876.

Sometimes the things these men found funny shows how humor has changed. During preliminary talks, a young Indian boy walked up to one of the commissioners and asked, “How are you, Dad?” The commissioner, Geminien P. Beauvais, who lived in St. Louis with his white family at the time but had spent his younger days as a fur trader, “gazed for a moment at the young fellow and then returned his salutation, as a look of recognition shot athwart the official countenance.” The young boy came to the council on behalf of himself and his four siblings “for the express purpose of seeing their mutual father and conveying to him expressions of their filial regard, though they had not seen him for a number of years.” While child abandonment is not considered funny today, the correspondent writes, “It was emphatically a case of “though lost to sight, to mem’ry dear,” and the scene was heartily enjoyed by the bystanders.” Most of the humor, unsurprisingly, included jests about misfortunes or the lack of civilization on the frontier. As one newspaperman observed about wagon travel, “You get bounced somewhat on the hummocks, and it is fun to see a wagon plunge into a creek. It is more fun if you don’t happen to be in the wagon.” Another correspondent wrote about the landscape that “…a more lonely, desolate country in which to live certainly cannot be found this side of Alaska or the Siberian regions.” Nebraskans still enjoy making dark jokes about blizzards or the wind, so this is another way we can connect to our ancestors. When asked about how to prepare for visiting the Red Cloud Agency, which was located in Dawes County near the present-day town of Crawford, one of the commissioners replied, “Get a demijohn of whisky and fill your trunk with cigars. You can procure a pack of cards out here.”

Red Dog’s village southeast of Red Cloud Agency.

Red Dog’s village southeast of Red Cloud Agency.

However, you know that these kinds of complaints were made in jest because the guy who truly disliked the land and the people and the lack of civilizations got thoroughly hazed. When Reuben Davenport of the New York Herald arrived at the Agency for the Council, he announced that he had experienced “all he wanted of living in tents” and demanded a “private apartment.” The agency trader “stared at the man in amazement, and then replied that as he was not running a Grand Central hotel, he could not, but that he could provide him with the same sleeping accommodations he himself enjoyed—that is a blanket and a buffalo robe and room enough on the floor to spread them out.” Davenport was upset, so the trader asked him if he wanted a glass of sherry. “‘Thank you, I will, sir,’ responded the Herald chap. ‘I’m very fond of sherry, but I never allow myself to drink anything stronger than wine of some sort.’” The trader, outwardly sympathetic, poured him a glass. Davenport knocked it back only to find the trader had poured him raw corn whiskey. Nobody saw Davenport for over a day, and, as the correspondent explains, “it was generally understood he was devoting his entire time and attention to the growing of a new coating to his tongue and the inside of his mouth.” While it’s not ready to debut as a stand-up comedy routine, despite its serious subject matter, this book is a lively and entertaining account of an important event in Nebraska history and U.S. history. You can purchase the book for $29.95 (NSHS member price: $26.96) by visiting one of our Landmark Stores or by calling 402-471-3447.