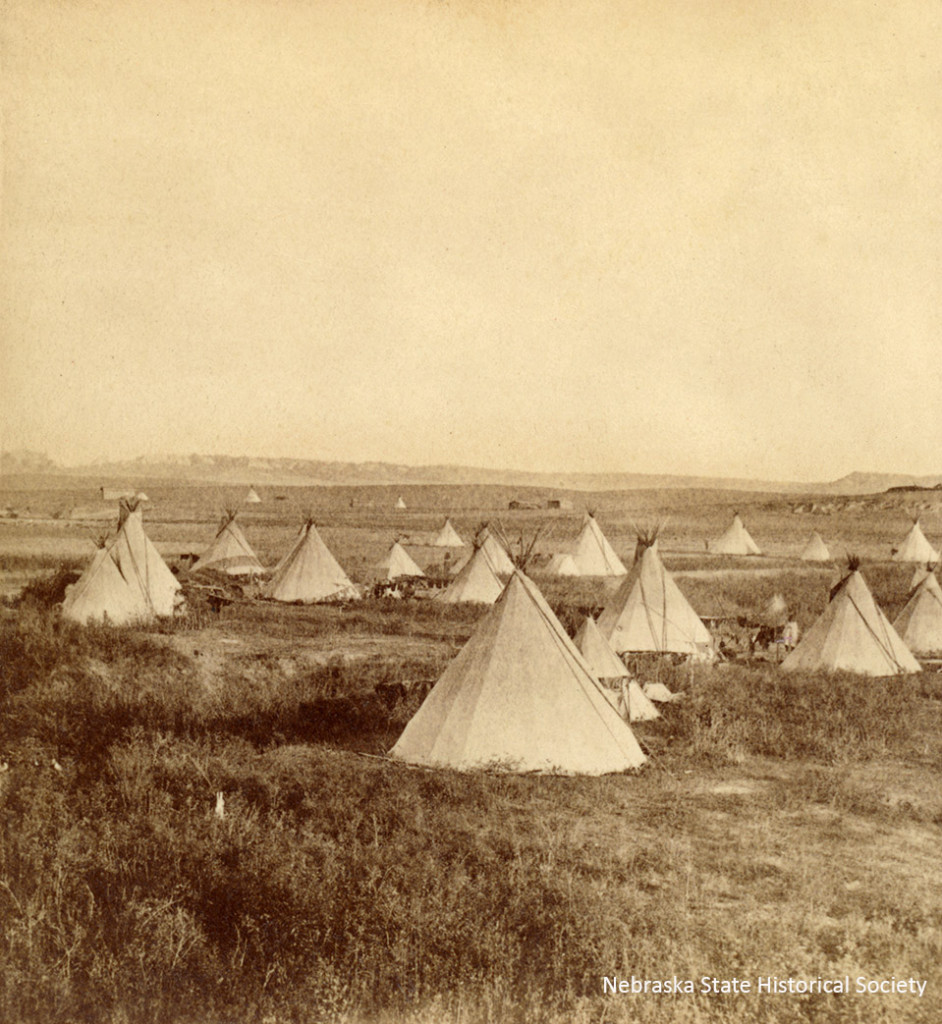

Red Dog’s village southeast of Red Cloud Agency.

Red Dog’s village southeast of Red Cloud Agency.

For a month in late summer 1875 the nation’s gaze was drawn to proceedings at the remote Red Cloud Agency in northwestern Nebraska. Home to Red Cloud’s Oglala division of the Lakota (Western Sioux), the agency had been chosen as the site for important negotiations between U. S. Government commissioners and the Indians.

The so-called “Grand Council” would focus on gaining the Indians’ agreement to cede ownership of the Black Hills, then a part of the Great Sioux Reservation. It was the second of two councils held in western Nebraska that were noteworthy for the issues involved, their effect on the future of Indian-white relations, and because they were among the largest such gatherings in American history.

The full story is detailed in “‘The Greatest Gathering of Indians Ever Assembled:’ The 1875 Black Hills Council at Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska” (PDF) by James E. Potter, from the Spring 2016 edition of Nebraska History.

By early September 1875 the number of Indians assembled within a fifty-mile radius of Red Cloud Agency, including women and children, may have approached 20,000 although estimates vary. They included the Oglala, Brulé, and associated Northern Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne from the Nebraska agencies, significant delegations from the Missouri River agencies, and a much smaller number of representatives from the non-agency bands. The White River valley and its tributaries must have offered an impressive sight, dotted as they would have been with hundreds of tepees and thousands of ponies. One observer called it “the last grand gathering of the greatest of the surviving Indian nations.”

Red Cloud Agency in 1876.

Red Cloud Agency in 1876.

Because the Black Hills gold discoveries had already received wide publicity and miners were already prospecting and building settlements there illegally, the government’s purchase of the Hills seemed crucial to preventing the outbreak of an Indian war. The council and its outcome became national news, and several newspapers sent correspondents to report both on the arrangements leading up to the council and on the council itself. They included the Omaha Bee, Omaha Herald, Chicago Tribune, New York Herald, Cheyenne Daily Leader, and New York Tribune, along with a few smaller newspapers.

Some correspondents were professional journalists, while others were army officers or civilian attachés of the Allison Commission hired by the papers to report on the proceedings. As they penned their letters for their respective newspapers, the reporters made little pretense of objectivity, even according to the slack journalistic standards of the day. Much of their writing reflects both the biases against and stereotypes of Indians that many Americans shared.

Although Indians had sometimes been portrayed as innocent children of nature or “noble savages,” by 1875 their resistance to American expansion into their homelands and their refusal to adopt white values and ways of living made it easy, particularly on the part of westerners, to characterize them as vicious, immoral, and lazy among other epithets, and almost sub-human. What’s more, while the Indians resisted efforts to “civilize” them according to the standards of white society, they were seen as being perfectly willing to adopt the whites’ worst vices, degrading themselves even further.

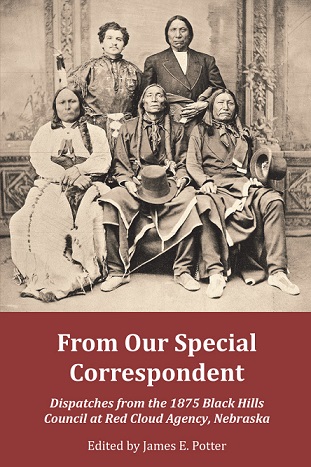

From Our Special Correspondent: Dispatches from the 1875 Black Hills Council at Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska, edited by James E. Potter

From Our Special Correspondent: Dispatches from the 1875 Black Hills Council at Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska, edited by James E. Potter

Although the correspondents condemned most aspects of Indian life and culture they observed at the agencies, some of what they wrote concerning the “uncivilized savages” standing in the way of American progress served, even if inadvertently, to highlight the Indians’ humanity and undercut the stereotypes. While the reporters were quick to characterize the Indians as “rascals” or “lazy, shiftless dogs” with “untutored minds,” and portray leaders such as Red Cloud and Spotted Tail as crafty, sullen, treacherous, or greedy, the accounts also revealed them to be rational and intelligent human beings with a hearty sense of humor who employed considerable diplomatic skill in defending their land and way of life in the face of great odds.

Interested in the rest of the story? Purchase the Spring 2016 edition of Nebraska History or buy “From Our Special Correspondent”: Dispatches from the 1875 Black Hills Council at Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska. The book is edited by Nebraska History associate editor James E. Potter. In addition to the letters themselves, the 344-page paperback includes an introductory essay, editorial notes, map, fourteen photographs, references, three appendixes, bibliography, and index.

(Posted 2016; updated links 2/8/2023)