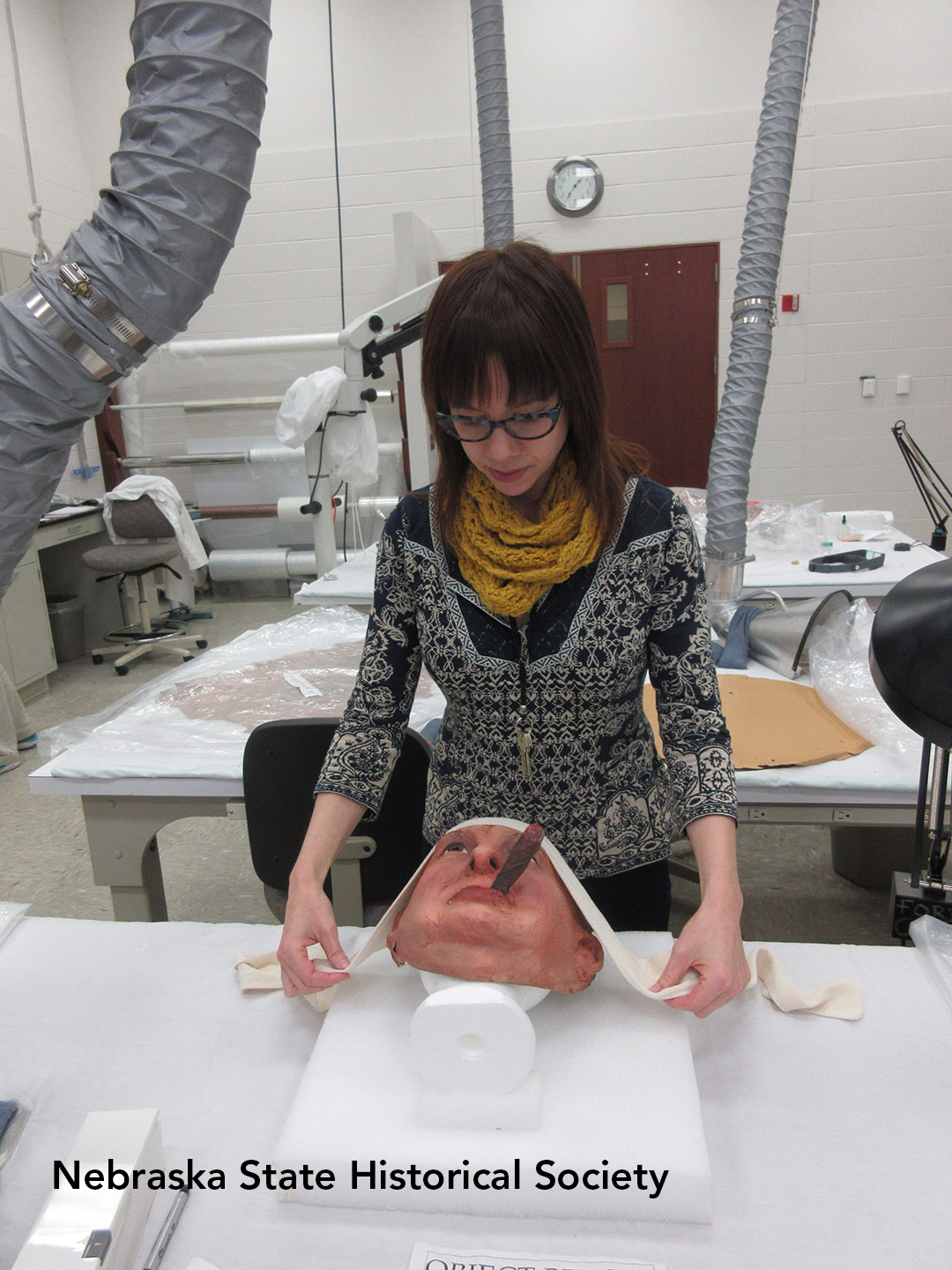

What’s more ghoulish than a historic mask of a long-dead celebrity? Any mask of a long-dead celebrity with wrinkles, tears, missing ears, or discoloration – or at least that’s how the conservators at the NSHS’s Ford Conservation Center feel. “The large spots of discolored adhesive make it look like he has leprosy or something,” says Rebecca Cashman, Objects Conservator.

The objects lab at the Ford Conservation Center in Omaha is currently busy with 30 masks that will soon be part of the “The Strange and Wonderful Masks of Doane Powell” exhibit at the Nebraska History Museum. In March, these masks will replace the first group of treated masks currently on display. That way, the masks aren’t subjected to the rigors of being on display for the entire ten months of the exhibit. The Doane Powell masks have been a huge group effort for the Ford Center. While each conservator usually works on projects related to his or her specialty (paper, paintings, or objects), the masks each consist of a three-dimensional layered paper substrate with a painted surface and additional elements composed of fabric, plastic, hair, and feathers (to name a few).Everyone has worked together to get these masks ready for display. Age and improper storage methods have left many of the masks in rough shape. Made primarily in the 1940s and 1950s, Powell’s masks were used in theater productions, circus performances, movies and television, advertising campaigns, magazine illustrations, store window displays, and at social functions. When the Nebraska native created the masks, he joined multiple layers of wood pulp kraft paper with glue, molding them over a facial sculpture of modeling clay on a rigid base. Each mask he created is one-of-a-kind.

Assistant Objects Conservator Rebecca Cashman works on one of the Doane Powell masks. This second round will go on display at the Nebraska History museum later this year. The first set of masks is already on display on the Museum’s first floor.

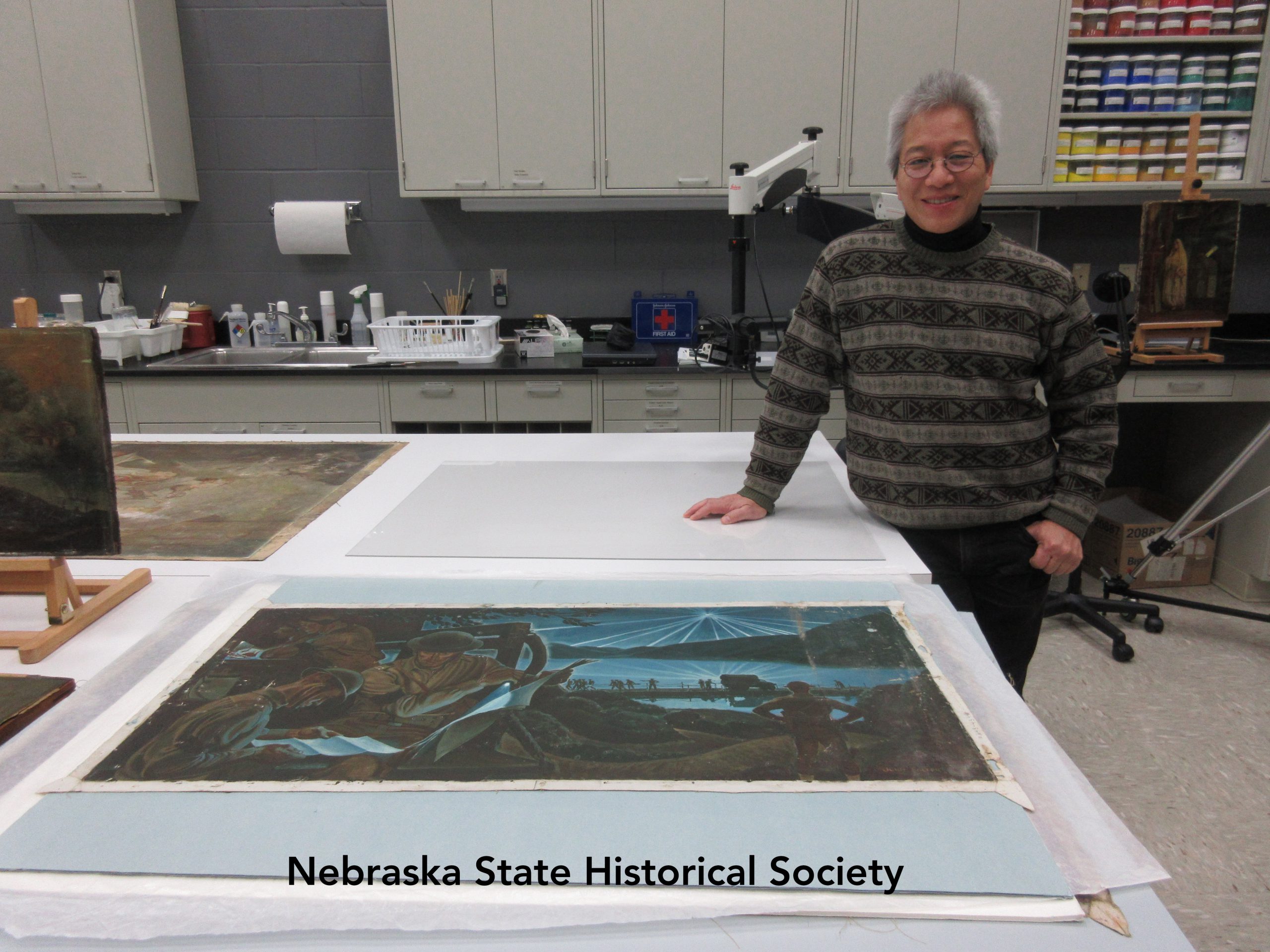

Kenneth Be, painting conservator at the Ford Center, is shown with a John Falter painting.

Paper conservator Hilary LeFevere and conservation technician Megan Griffiths work on paper objects at the Ford Conservation center.

Cashman works on a Doane Powell mask at the Ford Conservation Center.

As a result, conserving these objects requires a one-of-a-kind approach to clean and repair each mask. “There are about 70 masks and they’re not all painted with the same media,” Cashman says. She picks up a mask of early 20th century entertainer Sophie Tucker and points to Sophie’s lips. “In some cases we think actual makeup, like lipstick, was used to color some of the lips. ,” Cashman says. “We have to be very careful.” At the beginning of the project, Cashman carried out extensive testing on a group of masks to gain a sense of cleaning methods and repair materials that could be safely used to treat them without interfering with the original materials. Lab technicians Megan Griffiths and Vonnda Shaw, along with paper conservator Hilary LeFevere have all helped treat the masks, which once exhibited faces that were grey from accumulated dirt and grime. Some of the Powell masks had make up on the interiors from their various wearers, while others were just dirty from repeated use. Additional testing is carried out on each mask before treatment. Since the masks exhibit such a wide array of materials and problems, the treatment for each is individualized. The conservators have on hand a supply of tested repair materials, such as adhesives and mending materials that are best to help repair tears and add structural soundness.

Japanese tissue papers (which have long, intact fibers), cotton bandages, wax resins, wheat starch paste, and adhesives dripped into tears with syringes are just a few of the materials the conservators have used to stabilize the masks. Some of these materials are for mending, some are for adhering, and some, like the cotton bandages, are for reshaping the heads during humidification). Other repair methods involve carefully exposing the mask to controlled humidity “Sometimes you have to put the mask in a humidification chamber in order to make the paper components pliable enough to reshape them,” Cashman says. “But you don’t want the paper turning to mush, and you have to pay close attention to what is happening to the paint layer above, which reacts differently to moisture than the paint. I was really excited when I was able to successfully humidify politician Grover Whalen’s flattened head and reshape it so that it actually resembled him. “Sometimes I’ve had little chunks completely fall off,” Shaw says. “But I can put them back on because I’ve documented everything, and I know where they go.”(We should probably mention somewhere that Vonnda has repaired more masks than anyone for this project!) Handling is a major cause of damage to the masks, so Shaw designed special supports for each mask that would minimize this risk. The supports can be used during treatment, transportation, storage, and while the object is on display. They consist of an inert foam head with a flexible “pillow” to support the internal cavities of the facial features. Shaw says she spends about two and half to three hours on masks in good shape. That time also includes the time it takes to write reports and photograph her progress. Masks in poor shape can take five to eleven hours to clean and repair. “A mask of General MacArthur took a long time because he had a hat that was completely damaged,” Cashman says. “Elsie the Cow took closer to eleven hours because one of her horns were damaged and her horns were partially detached,” Shaw says.

Cashman hovers over the “unidentified man” mask again (whose head is spotted overall from discolored adhesive) and turns him with a fastidious touch. hovers over the “unidentified man” mask again (whose head is spotted overall from discolored adhesive) and turns him with a fastidious touch. Cashman hovers over the “unidentified man” mask again (whose head is spotted overall from discolored adhesive) and turns him with a fastidious touch. “The mask is losing its original hair, and the adhesive has discolored over time,” Cashman says. “We need to figure out the best way to read here the hair to head using materials that won’t affect the original paint. There is a particular heat-activated adhesive I think may work, but we need to make sure exposure to low heat from a tacking iron won’t damage the hair. We have to think about things like that.” Tacking irons are small, hand-held heating elements, and they are yet another tool the part-chemist, part-artist, part-therapist conservators use to repair and conserve the hundreds of items trusted to their care. Conservators at the Ford Center serve the conservation needs of both the NSHS and private clients. Those private clients include individuals, art museums, and history museums. “We don’t discriminate,” Cashman says. “A lot of clients bring in things that are important to their family that might not have a lot of market value but have a great deal of sentimental value.” Conservators and technicians in the objects lab will move on to other projects now that the Doane Powell mask project is winding down. Cashman sums up the main mission of the project succinctly. “They are caricature masks,” she says. “So they need to look like the person – they just can’t be disfigured or squashed.”

(Posted in 2017.)