By the start of the twentieth century the pain of death had been softened for many Americans. Professional undertakers, rather than family members, laid out and attended the bodies of the deceased, made coffins, dug graves, and directed funeral services. A few individuals, however, tried to insure that no such attentions would be paid them after death. In early July of 1914 several Nebraska newspapers published an interview with seventy-six-year-old Ernst T. Hunger of Lincoln, who had made his own coffin in order to spare his descendants the expense of buying one after his death. Hunger, who kept it on his front porch, also slept in it, pronouncing it “the most comfortable bed I ever got into in my life.”

The Kearney Daily Hub on July 8, 1914, published the first paragraphs of an interview with “E. T. Hunger, formerly chief of police of Lincoln [1912-13], [who] sleeps in his coffin. The homemade box stands on the front porch of the Hunger residence, and at night, after the neighbors have gone to bed, ‘Old Man’ Hunger goes out and climbs into the box. If the weather is cold or if a shower comes up he pulls the top of the coffin over the opening, leaves a crack through which he can get a little fresh air and calmly goes to sleep. Mr. Hunger is now seventy-six years old, and for many years he has been sleeping in his coffin.

“‘And I made that coffin myself, too,’ he says proudly. ‘Costs too much to die in these days. So I just thought I’d play a joke on the undertakers and make my own coffin while I was well enough to do it. So I got me some inch plank about a foot wide and several pieces of 2 by 4. I put the latter at each corner to make the box stable, and then I nailed it together with eight penny nails. Whole thing cost me less than $5, but it’s strong enough to hold a man about my size without any trouble. And won’t those undertakers be mad when I die and they can’t get any of my money?’

“The Hunger home sits back from the street, and there are trees all around it. In the summer these trees shade the porch and the gruwsome [sic] object cannot be seen plainly. But when winter strips the limbs and branches Mr. Hunger’s homemade coffin can be seen by all passersby.”

Hunger’s background was included in an uncut version of the interview published in the Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania) Press on July 5, 1914. Born in Germany in 1836, he fought in the Franco-Prussian War and then came to the U.S., where he worked at various positions in a dozen cities, before settling in Lincoln. He served as a constable there, and as Lincoln’s chief of police from 1912 to 1913.

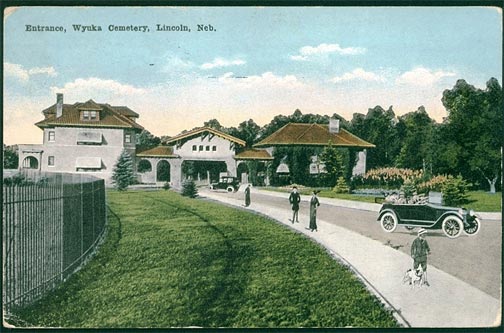

Hunger’s dislike of undertakers in 1914 may have arisen from numerous deaths in his family. Two daughters died in infancy, a twenty-three-year-old son in 1901, and his wife in 1912. One daughter survived after his death in 1925. Hunger, his wife, and son are buried in Lincoln’s Wyuka Cemetery.

This undated photograph on a postcard depicted the entrance to Lincoln’s Wyuka Cemetery, where the graves of Hunger, his wife, and his son are located. NSHS RG2133.PH12-335

From the Kearney Daily Hub, July 8, 1914.