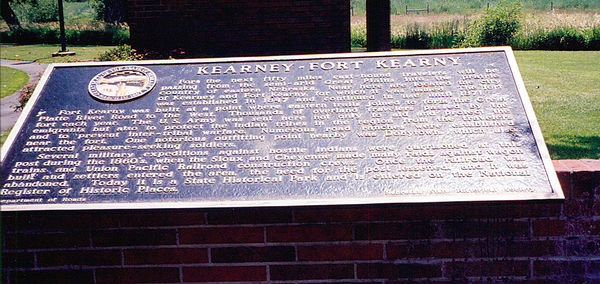

Marker Text

Note: The term “Indian” is used instead of “Native American” or “American Indian” as it was the common usage of the time this marker was cast.

For the next fifty miles east-bound travelers will be passing from the semi-arid Great Plains into the country of eastern Nebraska. Near here are located the city of Kearney and Fort Kearny, for which it was named. The fort was established in 1847 and continued in use until 1871. Fort Kearny was built at a point where eastern trails joined to form the Great Platte River Road to the West. Thousands of overland travelers passed by the fort each year. The U.S. Army was sent here not only to aid and protect the emigrants but also to protect the Indian tribes in the region from the travelers and to prevent inter-tribal warfare. Numerous road ranches were established near the fort. One notorious outfitting point nearby was Dobytown, which also attracted pleasure-seeking soldiers.

Several military expeditions against hostile Indians were garrisoned a this post during the 1860’s, when the Sioux and Cheyenne made many raids against wagon trains and Union Pacific Railroad construction crews. Once the railroad was built and settlers entered the area, the need for the post lessened, and it was abandoned. Today it is a State Historical Park and is entered on the National Register of Historic Places.

Marker Location

Interstate 80, Kearney, Buffalo County, Nebraska; 40.670663, -99.15709. View this marker’s location.

Further Information

Between 1848 and 1871, Fort Kearny was an important military outpost on the Great Plains and marked the beginning of the Platte River Road. The fort is named after General Stephen Watts Kearny but is frequently misspelled “Kearney.” The city of Kearney, located near the fort, perpetuates this old error.

The Old Fort Kearny

In 1844, a report by the Secretary of War recommended building a chain of military forts along the Oregon Trail to protect travelers. This plan was approved by Congress in 1846. One of the forts created was near Table Creek along the Missouri River and called Fort Kearny. Present-day Nebraska City is built near the old fort. Old Fort Kearny, as it came to be known, was not placed at an important location along the trail at that time. In 1847, the War Department decided to move Fort Kearny to central Nebraska, near the Platte River’s Grand Island.

The New Fort Kearny

On September 23, 1847, Lieutenant Daniel P. Woodbury led an expedition to select the new location of Fort Kearny. On October 2 he reached Grand Island (the feature, not the city, which had not yet been established) and selected a spot for the fort which was 197 miles west of the old Fort Kearny. This was an ideal location, he said, because it was elevated enough to avoid flooding, was close to good timber and had a central location to keep peace between the warring Pawnee and Sioux. On March 12, 1848, Battalion Commander L.E. Powell and some engineers left the old fort to begin work on the new fort. By May 1 the old fort was abandoned. The new fort was at first called Fort Childs, after a veteran of the Mexican War and friend of Lt. Woodbury. However, the War Department decided to rename it Fort Kearny. To avoid confusion, many people called the new fort “New Fort Kearny” or “Fort Kearny on the Platte.”

Fort Kearny and the Westward Migration

The fort was only one year old when the California Gold Rush of 1849 began. As such, it was under-manned and short on supplies. It was thus ill-prepared for the 30,000 people who traveled along the Platte in that year (though only 25,000 of these passed on the south side of the river near Fort Kearny.) Most of these travelers passed Fort Kearny between May 8 and June 22, with over half of all the travelers passing the fort between May 18 and June 2; on one day, May 24, between 500 and 600 wagons carrying between 2,000 and 2,500 people total passed the fort. The fort was so small at the time one pioneer wrote that the fort was “misnamed”: “[F]or there is neither wall nor picket, nor any fortification of any kind.” Another described the fort as “a number of rudely constructed huts built on the sods or turfs of the prairie, laid up after the manner of laying bricks.”

Despite this inglorious beginning, the fort quickly became a bulwark of American civilization on the plains. One pioneer wrote: On reaching [Fort Kearny], the emigrant feels that he has reached an oasis; he sees once more the evidence of civilization… [H]e fully realizes he is still protected, still inhabits America. The fort was important because it allowed pioneers to restock their supplies and receive news from home. The fort also provided medical care and other services. For the military, the fort was important as a base of military operations against the Plains Indians. Fort Kearny was never attacked, and no major battles occurred in its vicinity.

Fort Kearny marked the convergence of several westward trails. Routes from Independence, St. Joseph, Old Fort Kearny and Council Bluffs (later Omaha) all came together at the fort and continued on more or less the same route across most of the Platte (the Great Platte River Road). Travelers were forbidden from camping in the vicinity of the fort so the grazing land could be used by the military’s animals.

The officers at the fort also disapproved of migrants walking through the fort’s grounds. Some migrants had already run out of supplies by the time they reached the fort. Officers were allowed to sell supplies from the fort to these travelers. In some cases, when migrants had no money, they could be lent the supplies (and usually never paid them back). One traveler traded dried peaches and loaf sugar for 175 pounds of flour.

Relative to other forts on the frontier, like Leavenworth in Kansas or Laramie in Wyoming, Fort Kearny was never that large. The garrison generally did not exceed 200 men, and there about the same number of civilians on the fort at any given time. Even as the fort expanded in the 1850s, many migrants didn’t think of it as a fort since it never had any fortifications.

Two cities, Kearney City (Dobytown) and Valley City (Dogtown) developed in the vicinity of the fort. These started out as places for mail carriers to rest their horses and get food. Kearney City became famous for its plentiful bars and gamblers. These towns slowly disappeared after the railroad was built in 1866. The new town of Kearney, on the railroad line north of the Platte, became the municipal center of the area. When the railroad passed through the area along the north side of the Platte in 1866, with the fort’s usefulness running out, General William Tecumseh Sherman ordered that the fort be liquidated. Since it was still being used as an ammunitions testing area, it was not immediately torn down, but by 1870 only 50 men were stationed there. The last garrison finally left in 1871.

Later History

After the fort was abandoned by the military, the land was made available to homesteaders. In 1922, the Fort Kearny Memorial Association was founded and purchased 40 acres of land at the site of Fort Kearny, which consists of about half the land the fort formerly sat upon. In 1929 this land became a state park. None of the original fort stands today. The area surrounding the fort has been mostly developed with farms, so all traces of the old migratory trails are gone. Still, archeologists have identified the locations where several buildings once stood. Since few pictures or sketches of the fort were ever made, it is difficult to know what the fort used to be like; however, a replica of the blacksmith shop is now part of the park.