Our Historical Markers across Nebraska highlight fascinating moments in our state’s past. Today we’re highlighting a marker that tells the story of a people who lived in what is now Nebraska for hundreds of years before white settlers arrived: the Pawnee.

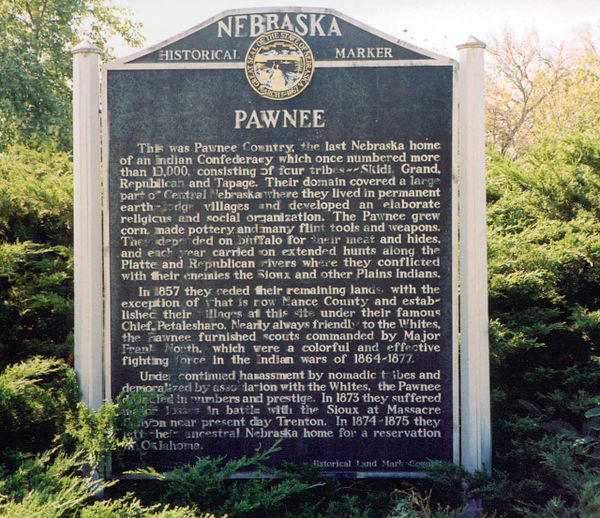

Marker Text

This was Pawnee Country, the last Nebraska home of an Indian Confederacy which once numbered more than 10,000, consisting of four tribes — Skidi, Grand, Republican and Tapage. Their domain covered a large part of Central Nebraska where they lived in permanent earthlodge villages and developed an elaborate religious and social organization. The Pawnee grew corn, made pottery and many flint tools and weapons. They depended on buffalo for their meat and hides, and each year carried on extended hunts along the Platte and Republican rivers where they conflicted with their enemies the Sioux and other Plains Indians.

In 1857 they ceded their remaining lands, with the exception of what is now Nance County and established their villages at this site under their famous Chief, Petalesharo. Nearly always friendly to the Whites, the Pawnee furnished scouts commanded by Major Frank North, which were a colorful and effective fighting force in the Indian wars of 1864-1877.

Under continued harassment by nomadic tribes and demoralized by association with the Whites, the Pawnee dwindled in numbers and prestige. In 1873 they suffered major losses in battle with the Sioux at Massacre Canyon near present day Trenton. In 1874-1875 they left their ancestral Nebraska home for a reservation in Oklahoma.

Marker Location

City Park, Genoa, Nance County, Nebraska; 41.44261, -97.73543

Further Information

Residents of what is now Nebraska for hundreds of years before white settlers arrived, the Pawnee have likely lived in Nebraska longer than any other current tribe.

Origins

The Pawnee came to the Great Plains earlier than other Great Plains tribes did. While many tribes associated with the Plains, like the Sioux, migrated to the Great Plains within the last few centuries, the Pawnee have lived in the region since at least the 1500s and possibly longer. There is some evidence that the Pawnee lived along the Republican and Loup Rivers between 1100 and 1400. The Pawnee language comes from the Caddoan language, meaning they are linked linguistically to the Caddo, Wichita and Arikara peoples. Because of this, it is believed the Pawnee were originally part of the Caddo people, who lived in the southern Great Plains (Texas and surrounding states), but migrated north. A part of this band became the Wichitas. Linguistic evidence suggests the Pawnee and Wichitas became separate tribes in the first few centuries A.D.

Early History

The Pawnee separated into four mostly independent bands: the Skiri, Chaui, Kitkahahki and Pitahawirata. The Skiri and Chaui seem to be the oldest of these bands; evidence of their settlements in villages near the Loup River (Skiri) and Shell Creek (Chaui) date to before the 1700s. The Chaui eventually spread to the Platte River and Skull Creek. The Kitkahaki and Pitahawirata split off from the Chaui some time before 1750. These bands were kept independent because marrying outside of one’s village was seen as upsetting the cosmic order. During the later 1700s, westward migration of white people pushed Indian tribes west of the Appalachians closer to the Great Plains. The combined threat of rival Indian tribes and white settlers caused the Pawnee to build bigger settlements. Each of the four Pawnee bands consolidated into one large village or town.

Traditions and Religion

Each of the four bands had its own take on Pawnee religion, but they shared some characteristics. The Skiri believed that the stars were transformed gods or fallen heroes. Skiri ceremonies were thus based on celestial movements. Unlike the other bands, the Skiri allowed anyone to join their ceremonies, even those not a part of their band. One peculiar Skiri tradition was the Morning Star Ceremony. The Skiri believed that human beings came from the marriage of the Morning and Evening Stars. The ceremony involved a reenactment of the marriage and included the sacrifice of a captive woman. It is one of the few cases of human sacrifice practiced by Indian tribes north of Mexico. The other three bands had no such ceremony. They focused their beliefs on animals.

All the Pawnee attributed supernatural powers to Ti-ra’wa, the mysterious life force of the universe. They also venerated corn, as they had a history of farming. The Skiri had a ceremony based on corn called the Corn Planting Ceremony, which was comprised of dances mimicking corn planting and hoeing coupled with songs about fertility. Like other Plains Indians, the Pawnee attached special meaning to the land. Fourteen sites are said to be sacred to the Pawnee, though only five of those have been found. Each of these places contained the lodges of the nahu’rac, animals with supernatural powers that were the gods’ representatives on earth. These animals could kill but could also cure disease, among other things. Groups of doctors in Pawnee society were named after the animal from which they received their power. Pawnees would visit these sacred sites to make offerings to Ti-ra’wa and to seek visions. The most sacred place was Pa:haku, located near Fremont. All the sacred sites except one were located between the Loup and Republican Rivers- the traditional Pawnee homeland.

The Pawnee Reservation

As whites moved into the area during the 1850s, conflicts inevitably arose between settlers and the Pawnee. When the chief of the Chaui, Te-ra-eta-its, and one of his companions went to a white man’s house to beg for food after their horses were stolen by other settlers, the man who owned the house shot and killed the chief. The settlers, fearful of more violence, called on the government to remove the Pawnee. The Pawnee said they would have accepted a reservation south of the Platte and away from the Sioux, but the government insisted they get one near the Loup River. On September 24, 1857, the Pawnee signed a treaty creating a reservation in modern-day Nance County, just west of Columbus. While the tribe received more money per acre than they had in their 1833 treaty, they still received very small payments. In the first five years of the treaty, they received only $6 per person in direct payments. In 1859, $10,000 was deducted from their annuities when a band of Pawnee terrorized settlers along the Elkhorn River. Four Pawnee died during the raids, and no whites were killed. Even though the Pawnee’s Indian Agent cautioned that many claims might have been fabricated, the government still punished the Pawnee for the full amount.

In 1857, a group of Mormons established the town of Genoa on land that would become part of the Pawnee Reservation. They were forced by the government to move off the land in 1860. The land the Pawnee were left with was generally good land, with 1,000 acres ready for cultivation by 1861. The Skiri, the largest of the four bands, occupied two villages to the west while the other three bands together occupied another village. Fears that the reservation was open to attacks from the Sioux were quickly realized. The villages were attacked eight times in the first year of the reservation; 13 Pawnee were killed in the fights. The government offered little protection. While the Pawnee did manage to fend off one invasion of Cheyennes in 1860, they were little match for the well-armed and numerous Sioux.

The Pawnee in the 1860s

Attacks, famine and inept governance greatly weakened the Pawnee reservation over the course of the 1860s. The population declined from 3,414 in 1861 to 2,325 in 1870. Ten thousand dollars were allocated to the tribe for the construction of a manual labor school, where the Pawnee could learn modern farming techniques. The school was built in 1866. However, the Pawnee resisted changing their farming methods, and, indeed, their crops often grew better than the ones planted by agency employees. Another key component of the reservation was the Indian school. The law demanded that every child between 7 and 18 go to school. The Indian school was designed to acculturate and segregate Pawnee children since the adults were deemed too difficult to Americanize. Despite the mandate of the law, only 79 children went to school in 1870. This was partly because the school had to give the students clothes, food and lodgings, and funding cuts made it difficult to accommodate any more students. Also, the Pawnee resisted the acculturation the school represented. They wanted to keep their traditions and not have their children cut off from them.

Removal

There remained 2,447 Pawnee in 1872, only 38.4% of the 1840 population. The gap between males and females was immense given the frequent warfare, and disease decimated the adult population; 43.4% of the population consisted of children. The same problems that had plagued the Pawnee for decades continued to wear them down. Matters only got worse in the 1870s. Settlers cut down trees on Pawnee land with impunity. The annuity payments were reorganized, giving the Pawnee less control over their resources. On May 2, 1873, the Pawnee were forbidden to leave the reservation without a pass. In 1873, between one-fifth and one-fourth of the Pawnee left for the Wichita Agency in Indian Territory. The Wichitas told them that their land was plentiful with game, and the poverty of the Pawnee land drove many from it. A grasshopper infestation the following year convinced the rest that moving south would be beneficial for the tribe. On October 8, 1874, the Pawnee agreed to a treaty agreeing to move to Indian Territory to live in a site of their choosing. The Pawnee left in waves, beginning in the fall of 1874; the last group did not leave until October of 1875. At first, the Pawnee lived with the Wichitas, but in June of 1875 they moved to their own reservation 150 miles away.

In Indian Territory

As it turned out, the land in Indian Territory was even worse than the Pawnee’s land in Nebraska. Disease was rampant. Between 1876 and 1885, half the population of the Pawnee was lost. Their culture began to disappear as well. The various ceremonies celebrated by the Pawnee were based on the cycles of weather and harvest. These traditions were hard to maintain in the new climate of Indian Territory.

Allotments

The Dawes Act was passed in 1887. This bill forced Indians on reservations to accept individual allotments of land, replacing the communal ownership of the reservations. Each family would be given a certain amount of land, and all the excess land in the reservation would be sold. The Pawnee were not put on allotments until 1893. So few Pawnee remained at that time that well over half of their reservation was sold as surplus land. They were given an advance of $80,000 for the land, which was sold for $212,916.71; the $132,916.71 of remaining money was not given to the tribe until 1920. The move to allotments did not help the Pawnee prosper. By 1900, only 650 Pawnee remained.

The Pawnee in the 20th Century

The “Indian New Deal” of the 1930s sought to give tribes more control over their own affairs by allowing tribes to create their own governments. The Pawnee set up a government under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act in 1936. Between 1946 and 1962, the Pawnee were awarded $7,316,096 in return for lands bought from the tribe for “unconscionably” low prices. The Pawnee are still governed by their tribal government located in Oklahoma.

Bibliography / Reading List

Wishart, David J. An Unspeakable Sadness: The Dispossession of the Nebraska Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 1994.

Wishart, David J., “Pawnees” in David J. Wishart, ed. Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004, 590-591.