by Rob Bozell, History Nebraska, State Archeologist

In addition to a world-wide pandemic, social justice protests, murder hornets, western wildfires, and coin shortages, 2020 is also the 300th anniversary of the 1720 Pedro de Villasur Expedition and the 200th anniversary of the 1819-20 Stephen Long Expedition. Many other important historic expeditions have crossed portions of Nebraska including those of: Lewis and Clark, Zebulon Pike, the Mallet Brothers, Étienne Bourgmont, G.K. Warren, John C. Frémont, and Prince Maximilian and Karl Bodmer.

By their very nature, ‘expeditions’ do not stay in any one place for extended periods of time and leave scant archeological signatures. Scholars have had greater success in identifying places that expeditions visited like Native American earthlodge villages and major geologic landmarks and also at identifying forts and other facilities that developed as a result of expeditions. Attempts to discover sites specifically associated with major Nebraska expeditions have met with limited success. Let’s look at a sample of three archeological research projects designed to discover remnants of expeditions.

The Villasur Expedition

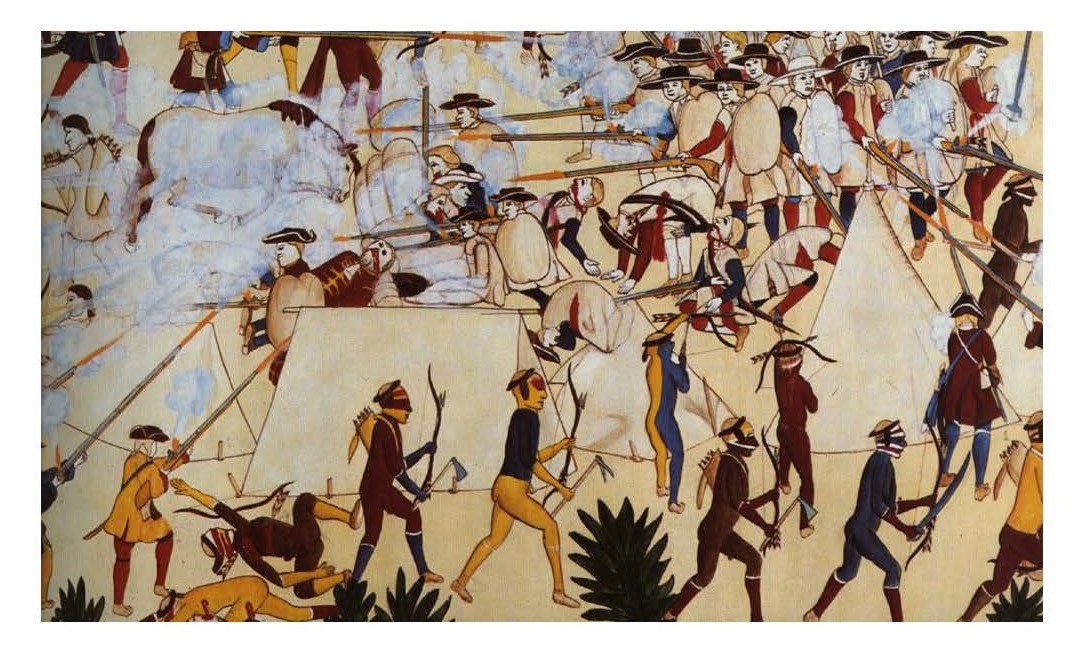

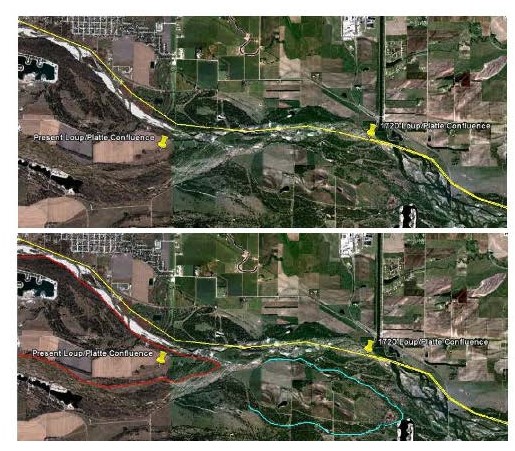

Don Pedro de Villasur’s 1720 journey into central Nebraska from the Southwest ended in disaster for the party when they were attacked by a combined force of Pawnee and Oto warriors in league with the French (Steinke 2012). According to archival documents, the battle occurred where the Loup River empties into the Platte River near present-day Columbus. A remarkable depiction of the fight is illustrated in a painting placed on stitched-together hides and a beautiful replica of it was produced by History Nebraska and is presently on display at the Nebraska History Museum (https://history.nebraska.gov/visit/villasur-massacre-hide-painting-reproduction). While vague accounts about the discovery of Villasur-related Spanish objects have been offered, none of it is definitive (Bryan 2020; Hill et al. 2015). Attempts to find the battlefield also have come up short-handed but not for lack of trying. The best treatment of these efforts is by Ben Bilgri (Bilgri 2012). Bilgri carefully explains how shifting river channels has almost certainly scoured away the site. The Loup-Platte confluence is now about two miles from where it was 300 years ago.

Replica of hide-painting depicting the 1720 Villasur massacre (History Nebraska).

Depiction of the modern and probable 1720 Loup-Platte confluence which are over two miles apart (Bilgri 2012:119).

Camp Alexis and Buffalo Hunt Diplomacy

In January of 1872, Russian Grand Duke Alexis was treated to a United States-sponsored buffalo hunt in Hayes County, Nebraska. The royal affair was hosted by Major General Philip Sheridan and participants included iconic western figures such as Brule Chief Spotted Tail, Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer, and William F. (“Buffalo Bill”) Cody. Due in large measure to the efforts of Hayes County citizens, the campsite location associated with the imperial hunt was well known when esteemed military archeologists Douglas Scott and Peter Bleed planned an investigation (Scott et al. 2013).

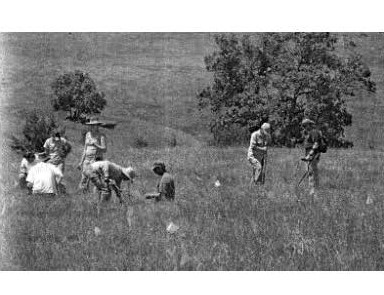

In 2008 and 2009, Scott, Bleed, and teams of University of Nebraska-Lincoln archeology students mapped the site and recovered artifacts related to the several day camp which was located along the upper reaches of Red Willow Creek—a Republican River tributary. Recovered objects related to the royal hunt include several Native American tools and a silver earring dangle similar to ones known to have been worn by Spotted Tail. Military and civilian items found include buttons, nails, buckles, horse equipment, tin cans, ceramics, cartridges, and bullets. Careful analysis of historic photographs and the present landscape also enabled the identification of specific locations including where the Duke’s tent was pitched. The history and archeological investigation of the Camp Alexis event is a wonderful example of historic period archeology and microhistory.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln archeology team plotting finds at Camp Alexis in 2008 (Scott et al. 2013:113)

1872 views of Grand Duke Alexis’s tent and dining tent overlaid on modern landscape (Scott et al. 2013:147).

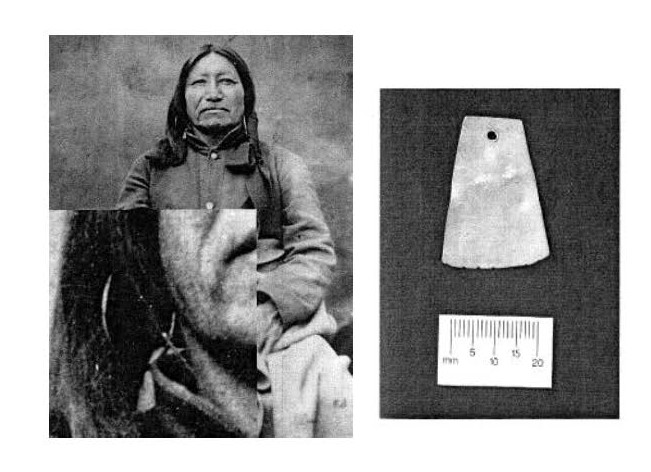

Chief Spotted Tail at Fort Laramie, 1868 (History Nebraska). The hoop earring in the inset (right) has a dangle resembling one found at Camp Alexis (left). (Scott et al. 2013:118-119).

The Long Expedition and Engineer Cantonment

The 1819-1820 Stephen Long Expedition was an important government-sponsored scientific journey across the central and southern Great Plains and the eastern slope of the Colorado Rockies (Fogerty 2018). One key element of the project was a 9-month encampment north of present-day Omaha where party members collected natural history specimens and interacted with local tribes. The camp was called Engineer Cantonment and the work done there formed the basis for much of the initial documentation of eastern Plains flora, fauna, geology, cartography, and tribal customs.

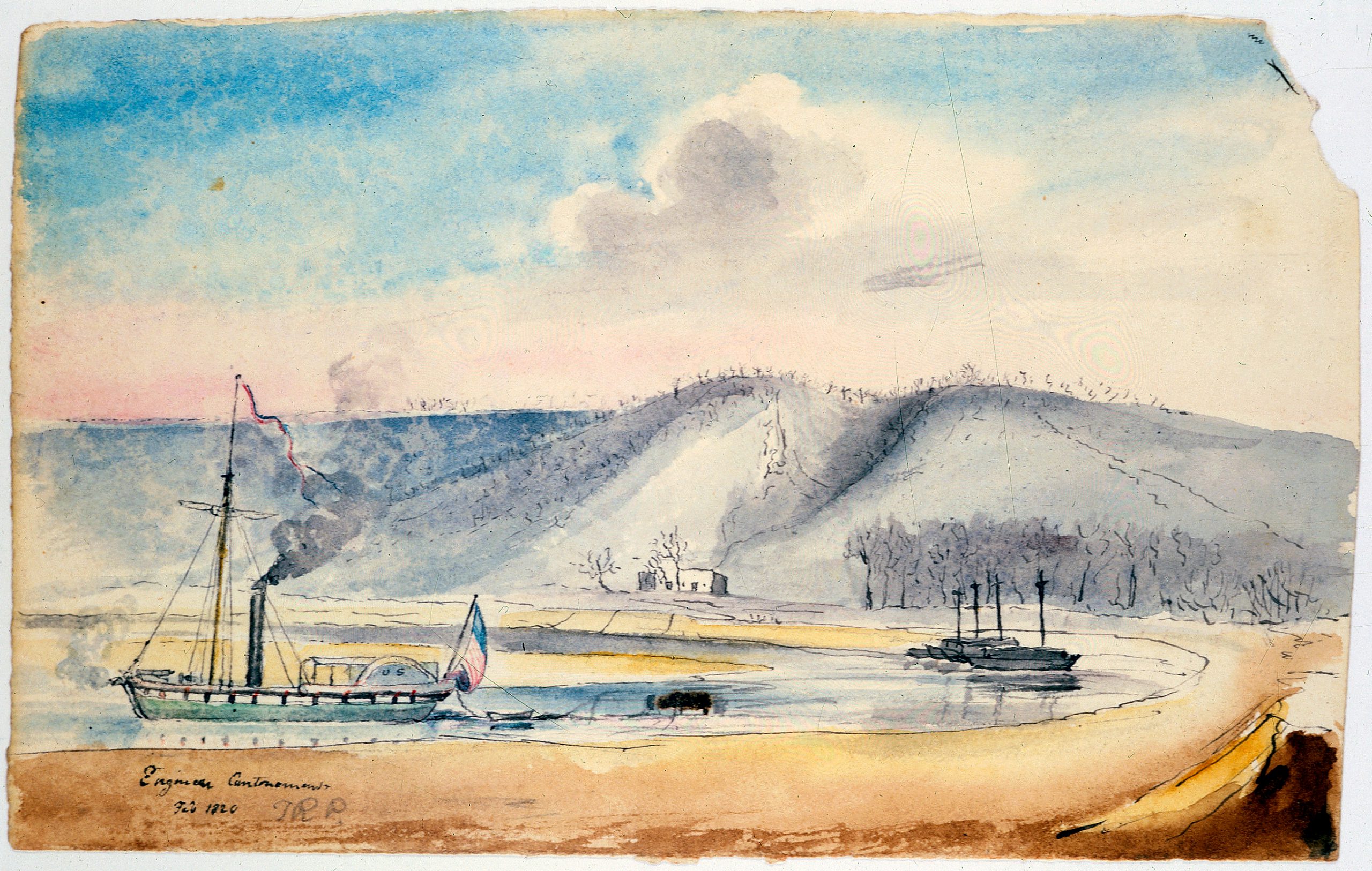

The location of Engineer Cantonment was imprecisely known and thought to have also been a victim of a shifting river channel much like the site of the Villasur fight. In 2003, a team of archeologists from History Nebraska used careful analysis of an 1820 painting of the camp along with remote sensing and mechanical trenching to discover that the site remained intact and contained the buried ruins of log cabin foundations and abundant period artifacts, animal bones, and botanical specimens related to the Long Expedition research (Bozell et al. 2018).

1820 painting of Engineer Cantonment by Titian Peale (American Philosophical Society, APSimg5646).

Sample of artifacts collected from the ruins of Engineer Cantonment cabins.

REFERENCES CITED:

Bozell, John R., Gayle F. Carlson, and Robert E. Pepperl (eds.)

2018 Archeological Investigations at Engineer Cantonment: Winter Quarters of the 1819-1820 Long Expedition, Eastern Nebraska. Publications in Anthropology 12. History Nebraska, State Archeology Office. Lincoln.

Bilgri, Benjamin J.

2012 Ambushed at Dawn: An Archeological Analysis of the Catastrophic Defeat of the 1720 Villasur Expedition. Master of Arts Thesis in Anthropology. University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses/21/.

Fogerty, Nic

2018 The Long Expedition—An ESRI Story Map.

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=f47d520bbe0c46f79956ccdb749f182c.

Hill, David V., John R. Bozell, and Gayle F. Carlson

2015 Olive Jar Ceramics from the Eagle Ridge Site (25SY116) in Eastern Nebraska: Booty from the Villasur Expedition? Kiva 80(3-4).

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00231940.2016.1151154

Scott, Douglas D., Peter Bleed, and Stephen Damm

2013 Custer, Cody, and Grand Duke Alexis: Historical Archaeology of the Royal Buffalo Hunt. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman.

Steinke, Christopher

2012 Leading the “Father” The Pawnee Homeland, Coureurs de Bois, and the Villasur Expedition of 1720. Great Plains Quarterly 32:1. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2753/.

https://history.nebraska.gov/visit/villasur-massacre-hide-painting-reproduction