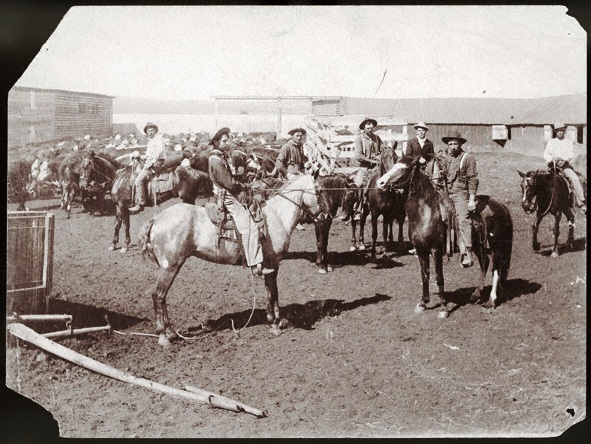

Lee Brothers Ranch at Brownlee, Cherry County, in 1900. RG2608-1837 (left). By the mid-1870s Nebraska’s open-range cattle industry, centered in the western Platte Valley and the Panhandle, was experiencing growing pains. Concerns included introduction of Texas cattle to supply the Indian agencies, unregulated “round-ups” that caused ownership disputes (in winter, long hair made brands hard to see), and bulls running at large year round. These problems prompted cattlemen to meet at Ogallala on February 11, 1875, to organize “The Stock-Growers Association of Western Nebraska” encompassing Lincoln, Keith, and Cheyenne counties and all unorganized territory lying to the north. The association asked the state legislature to authorize stock inspectors and limiting the roundup period to May 15 through November 15. The law was promptly passed.

Lee Brothers Ranch at Brownlee, Cherry County, in 1900. RG2608-1837 (left). By the mid-1870s Nebraska’s open-range cattle industry, centered in the western Platte Valley and the Panhandle, was experiencing growing pains. Concerns included introduction of Texas cattle to supply the Indian agencies, unregulated “round-ups” that caused ownership disputes (in winter, long hair made brands hard to see), and bulls running at large year round. These problems prompted cattlemen to meet at Ogallala on February 11, 1875, to organize “The Stock-Growers Association of Western Nebraska” encompassing Lincoln, Keith, and Cheyenne counties and all unorganized territory lying to the north. The association asked the state legislature to authorize stock inspectors and limiting the roundup period to May 15 through November 15. The law was promptly passed.  Cowboy and herd in Cherry County in 1889. NSHS RG2608-3300 (left). The association drafted a constitution and by-laws, membership qualifications (ownership of at least 100 cattle), and organized the first official “round-up” to begin May 15, 1875. It would commence at Sidney. “The course to be pursued from Sidney shall be up Pole Creek to Pine Bluff, thence to Creighton’s herd on Horse Creek.” The round-up would then work east down both the South and North Platte rivers. At the same time another party would start from Nichols Station on the Union Pacific Railroad west of North Platte and proceed west along the two rivers. “They will work the cattle as far up as Ash Hollow.” By June 24, the North Platte Western Nebraskian could report, “Thus far, the round up as been very satisfactory in every respect.” The association soon adopted more detailed rules. In 1876 the stockmen were to assemble at Nichols Station on May 20. Then, “the round-up will proceed west until they reach Ogallala at which point a sufficient force shall be stationed to keep all cattle west of that point that have not been rounded-up. From thence, the party will proceed west until they meet the party conducting the Cheyenne County round-up.” For the first time the association specified the number of men each member was to furnish, based on the number of cattle owned. A member with 100 cattle had to provide one man; those owning from 2,500 to 3,000 cattle were to furnish nine men. One additional cowhand was requested for each 100 head exceeding 3,000.

Cowboy and herd in Cherry County in 1889. NSHS RG2608-3300 (left). The association drafted a constitution and by-laws, membership qualifications (ownership of at least 100 cattle), and organized the first official “round-up” to begin May 15, 1875. It would commence at Sidney. “The course to be pursued from Sidney shall be up Pole Creek to Pine Bluff, thence to Creighton’s herd on Horse Creek.” The round-up would then work east down both the South and North Platte rivers. At the same time another party would start from Nichols Station on the Union Pacific Railroad west of North Platte and proceed west along the two rivers. “They will work the cattle as far up as Ash Hollow.” By June 24, the North Platte Western Nebraskian could report, “Thus far, the round up as been very satisfactory in every respect.” The association soon adopted more detailed rules. In 1876 the stockmen were to assemble at Nichols Station on May 20. Then, “the round-up will proceed west until they reach Ogallala at which point a sufficient force shall be stationed to keep all cattle west of that point that have not been rounded-up. From thence, the party will proceed west until they meet the party conducting the Cheyenne County round-up.” For the first time the association specified the number of men each member was to furnish, based on the number of cattle owned. A member with 100 cattle had to provide one man; those owning from 2,500 to 3,000 cattle were to furnish nine men. One additional cowhand was requested for each 100 head exceeding 3,000.  Nebraska cowboys at Round Valley in Custer County, 1888. NSHS RG2608-1423 (left). An eyewitness account of the 1876 roundup appeared in the North Platte Western Nebraskian, June 17, 1876, under the headline, “The Round-Up; A Graphic Description by one that has often been with the Cow-Boys; An Annual Scene in Western Nebraska. “. . . The cattle [were] sighted, scattered here and there in bunches, ranging from five to two hundred head, which at sight of a horseman would break and run. Then comes the excitement—up gulch, down canyons, over hills and table-lands, on a long steady run, in their vain efforts to escape from the boys who are pursuing them, horses and riders equally thrilled with the excitement of the chase; ‘tis grand, exhilarating, and as the cattle are overtaken, checked and put with another bunch or bunches, they are then driven to the rodeo ground. Then comes the separation or ‘cutting.’ A band of a thousand head [is] surrounded by twenty horsemen or more. One party, employees of the owner, enter the herd, select the animals bearing the owner’s brand and mark, cutting each animal from the main herd and making a bunch of that brand until all are separated. This ‘cutting’ is exciting work. Now going at full speed as the animal makes an effort to get again with the main bunch; now stopping and wheeling as quick as a flash of lightning, dodging, twisting, until the animal perceives the folly of its efforts and permits itself to be driven to the bunch or brand where it belongs. No horsemanship can excel that which is displayed by an experienced cow-boy. As they dash over the rough prairie at the top of their mustang’s speed, [avoiding] great numbers of holes, the work of prairie dogs and our family of sub-soilers, the utter disregard of their peril is something as courageous as it is rash. The training of the ‘cutting’ horses is something wonderful. No matter what distance the cutting horse has traveled, how fatigued it may be, the moment you ride it into the herd every muscle, every faculty, is on the alert and the intelligence they display is something almost human; and occasionally you hear a cow-boy speaking of his favorite, ‘He knows more than most of men,’ is the usual expression. “All the cattle separated, each man holds his brand separate, another bunch is gathered and separated until night. . . . Such is the routine, each day having its incidents. In case of dispute as to who owns an animal, the animal is lassoed, thrown down, and all marks examined and the ownership is readily proven. A great many true gentlemen can be found among these wild fellows, men that are honest, intelligent, and when one offers his friendship, it is a friendship that will stand all tests.” – James E. Potter, Senior Research Historian/Publications

Nebraska cowboys at Round Valley in Custer County, 1888. NSHS RG2608-1423 (left). An eyewitness account of the 1876 roundup appeared in the North Platte Western Nebraskian, June 17, 1876, under the headline, “The Round-Up; A Graphic Description by one that has often been with the Cow-Boys; An Annual Scene in Western Nebraska. “. . . The cattle [were] sighted, scattered here and there in bunches, ranging from five to two hundred head, which at sight of a horseman would break and run. Then comes the excitement—up gulch, down canyons, over hills and table-lands, on a long steady run, in their vain efforts to escape from the boys who are pursuing them, horses and riders equally thrilled with the excitement of the chase; ‘tis grand, exhilarating, and as the cattle are overtaken, checked and put with another bunch or bunches, they are then driven to the rodeo ground. Then comes the separation or ‘cutting.’ A band of a thousand head [is] surrounded by twenty horsemen or more. One party, employees of the owner, enter the herd, select the animals bearing the owner’s brand and mark, cutting each animal from the main herd and making a bunch of that brand until all are separated. This ‘cutting’ is exciting work. Now going at full speed as the animal makes an effort to get again with the main bunch; now stopping and wheeling as quick as a flash of lightning, dodging, twisting, until the animal perceives the folly of its efforts and permits itself to be driven to the bunch or brand where it belongs. No horsemanship can excel that which is displayed by an experienced cow-boy. As they dash over the rough prairie at the top of their mustang’s speed, [avoiding] great numbers of holes, the work of prairie dogs and our family of sub-soilers, the utter disregard of their peril is something as courageous as it is rash. The training of the ‘cutting’ horses is something wonderful. No matter what distance the cutting horse has traveled, how fatigued it may be, the moment you ride it into the herd every muscle, every faculty, is on the alert and the intelligence they display is something almost human; and occasionally you hear a cow-boy speaking of his favorite, ‘He knows more than most of men,’ is the usual expression. “All the cattle separated, each man holds his brand separate, another bunch is gathered and separated until night. . . . Such is the routine, each day having its incidents. In case of dispute as to who owns an animal, the animal is lassoed, thrown down, and all marks examined and the ownership is readily proven. A great many true gentlemen can be found among these wild fellows, men that are honest, intelligent, and when one offers his friendship, it is a friendship that will stand all tests.” – James E. Potter, Senior Research Historian/Publications

Become a Member!

Our members make history happen.