At the brink of the Civil War, Nebraska Territory abolished slavery in 1861. As the war proceeded, many Nebraska soldiers fought for the Union while those at home kept up with events in the South. Though the territory prohibited slavery, the matter remained controversial.

So what did Nebraskans think about slavery during the war?

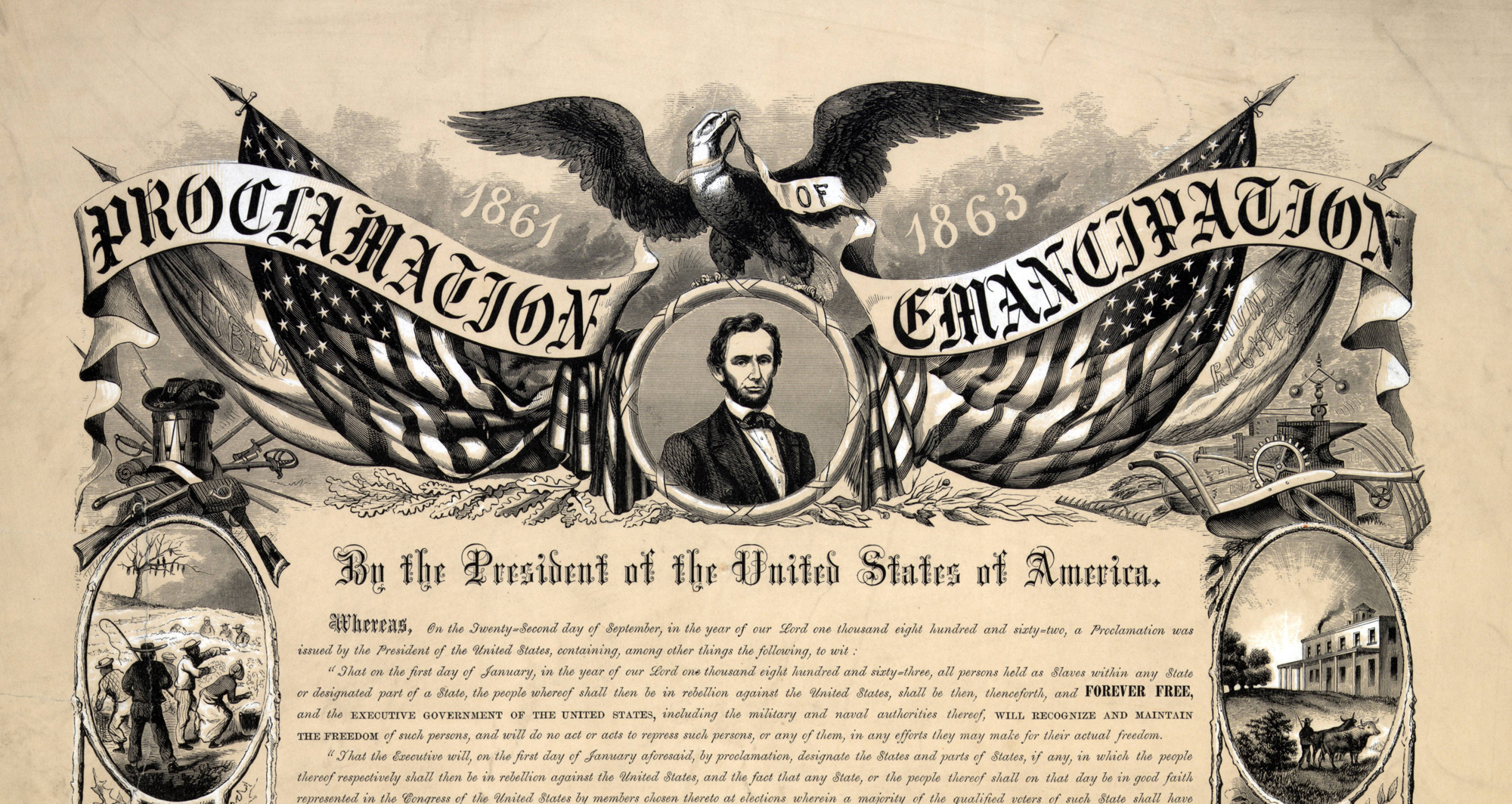

(The Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln.)

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

At the brink of the Civil War, Nebraska Territory abolished slavery in 1861. As the war proceeded, many Nebraska soldiers fought for the Union while those at home kept up with events in the South. Though the territory prohibited slavery, the matter remained controversial.

So what did Nebraskans think about slavery during the war?

One example of conflict happened in early 1863. Two Nebraska City newspaper editors were at each other’s throats after four Black men were reportedly chased out of town at gunpoint. Both The News and The People’s Press shared the story, but had different opinions about it. The News editorialized that Nebraska was no place for African Americans, regardless of status (free or enslaved). The People’s Press fired back, denouncing the mob and calling The News and its editor, Augustus Harvey, “barbarous.” Harvey then circulated a petition justifying the expulsion of Blacks, but few citizens signed it.

Generally speaking, a majority of the state’s Democratic population favored slavery. By abolishing it, they feared that problems would arise, particularly regarding agriculture and labor. J. Sterling Morton, politician and former editor of The News, argued that abolition would diminish the market for Nebraska’s crops and livestock. He wrote that “without slavery, the south could no longer raise cotton and would substitute corn, wheat and pork. By abolishing slavery, you abolish industry and prosperity of your own people.” People also worried that many freedmen would move north and compete with White laborers or mingle with White women.

Responding to the Emancipation Proclamation, a Democratic paper in Omaha described the document as “ill-starred, unauthorized and indefensible.” While most Northern Democrats did not support Southern secession, their slogan was “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was.” Strongly opposing the administration, Democrats called President Lincoln and his supporters “black republicans” who sought to “elevate an inferior race.”

Republicans were predominantly anti-slavery, even though few of them had favored immediate abolition of slavery before the war. Believing that the United States was framed on the basis of slavery, many Republicans felt that the nation’s founders had “compromised with wrong for the sake of unity,” as one man stated in a Nebraska Advertising article.

While most Republicans were against slavery to some degree, many of their reasons were unrelated to justice for African Americans. Republicans emphasized the benefits of “Free Labor” (meaning working for wages but being free to leave your employer and find another). Republicans feared the spread of the plantation system in which a small number of landowners dominated the economy. They feared that small farms and White labors would find themselves competing against the “Slave Power.” They feared plantation farms would monopolize and take away from small farms.

There were others, however, that did feel strongly that slavery was unjust to Black people. One man, whose letter was published in the Nebraska Advertiser, expressed his disgust by saying that people needed to pray to God to “pardon the awful crime committed against him” and to pardon the government. He said he was grateful that there were people in government with a “nobler mind and purer heart” that sympathized for slaves, and concluded that “slavery is dead, DEAD, yes dead forever.” Many Republicans that shared these views also labeled Democrats as “disloyal” and “secessionist sympathizers.”

Disagreements continued after the war. When in 1866 the Republican-led Congress voted to establish the Freedmen’s Bureau to aid formerly enslaved people, President Andrew Johnson vetoed the bill. His veto message was published in newspapers across Nebraska Territory. In his message, he explained that freedmen should be “self-sustaining” and that his intention was not to “feed, clothe, educate or shelter” them as implied in the bill.

At the conclusion of The Civil War, Nebraska was on its way to becoming a state. In the original draft of the state’s constitution however, there was a “whites only” voting provision. Congress demanded that the voting restriction be removed and in 1867, Nebraska claimed its statehood. That same year the state’s seal read “Equality before the Law,” symbolizing the extension of voting rights to African American men.

(The Great Seal of Nebraska. For many years this was a skylight window at the US Capitol. History Nebraska 7434-2)

Captions (two middle images):

(1) Advertisement for the organization of a volunteer military company at Brownville, Nebraska Territory. Nebraska Advertiser May 23, 1861.

(2) Morton in 1889. History Nebraska RG1013-20-12

Sources:

James E. Potter (2012) “Standing Firmly by the Flag: Nebraska Territory and the Civil War, 1861 – 1867,” University of Nebraska Press

Nebraska Advertiser — April 6, 1865

Nebraska Advertiser — March 8, 1866

Nebraska Advertiser — October 25,1866

Links:

“Equality Before The Law” : Thoughts on the Origin of Nebraska’s State Motto

Categories:

Slavery, Civil War, Statehood, J. Sterling Morton,