When world famous stage actress Sarah Bernhardt came to Omaha in 1901, it was a big deal. Over 2000 people were overjoyed to watch her perform. But many couldn’t understand a single word.

Sarah Bernhardt was a French stage actress of the 19th and early 20th century who as famous in her day as any big-name Hollywood actress in our own time. When she performed in Omaha in 1901 it was front-page news.

Above: Bernhardt, age 53, in 1901. Wikimedia Commons

In our time of 24-hour news and overexposed celebrities, it’s hard to appreciate what a big deal it was for up-and-coming Omaha to host the international stage star. On February 6, a reporter for the Omaha Daily News commented on the preparation of the actress’s dressing room at the Boyd Theater:

“Every stitch and stick of the usual furnishings had been removed. The floor had been carpeted and the wall covered with tapestries. . . . From the door of the room to the points where Bernhardt was to enter the various scenes new, clean canvas had been stretched for her to walk on, that her wonderful gowns should not come in contact with the dusty stage.”

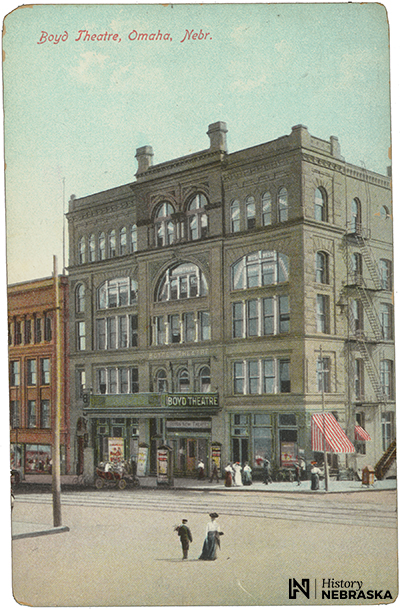

Boyd Theater, 1621 Harney Street in Omaha. The building was demolished in 1920. History Nebraska RG2341-523

More than 2,000 people saw and heard Bernhardt playing the lead role in the well-known drama La Tosca. “Most of Omaha’s fashion and a large representation of its brains was at the Boyd last night to ‘see Bernhardt,’” said the Daily News.

There was just one small issue. The play was in French. Most of the audience literally did not understand a word.

And here is where the reporter becomes a little tongue-in-cheek as he describes audience reaction to the famously proud and touchy superstar:

The audience rose admirably to the necessity of saving Omaha’s artistic reputation, and by way of doing so, recalled the actress several times at the end of the third act, and also after the fourth. She seemed pleased, but she is disappointed when she is anything less than delighted.

As for enthusiasm, how could there be enthusiasm when every person in the audience save six or eight was peering at the stage through a dense fog of lingual ignorance and was nervously uncertain just when enthusiasm would be acceptable to the divinity?

Bernhardt’s acting style would seem campy by today’s standards. In her day—before microphones and amplification—an actress had to reach the back rows with her unaided voice. In this, Bernhardt excelled. She was known for “the bell-like sweetness and clearness and the indescribable individuality” of her voice—and this, said the reporter, has “not been one whit exaggerated.”

But as to what she and the other actors were actually saying, most of the audience could only guess. If the crowd seemed a bit subdued through much of the performance, the reporter suggested that Bernhardt’s ability to “sustain the interest of the unenlightened to the pitch reached by the average good performance in the English tongue, shows the power of her interpretation of meanings without words.”