1893: After spending years playing in the minor leagues, Falls City native Charles Abbey makes his major league debut.

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

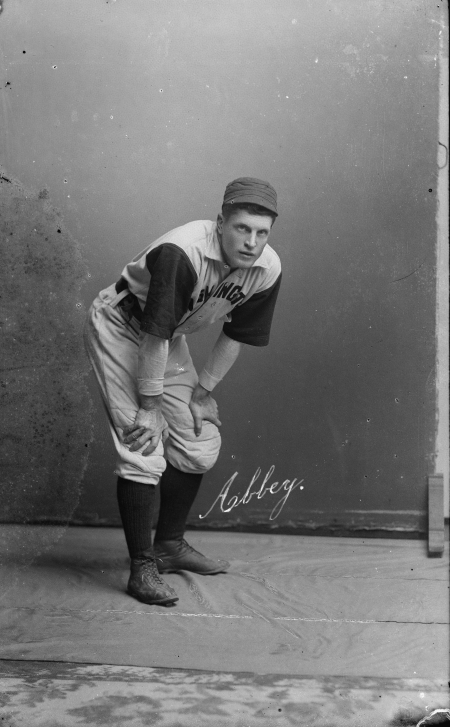

Chances are you won’t find his name anywhere among your baseball collections or referenced in any popular sports literature. Charlie Abbey wasn’t a Babe Ruth, Willie Mays, or a Lou Gehrig; he didn’t have any records that gained him that kind of fame. But he was the first native Nebraskan to play major league baseball.

David Alan Johnson shares how in 1893 this Falls City native earned spot on the Washington Senators roster in “’Abbey Dazed Them’: Nebraska’s First Major League Baseball Player,” featured in the Spring 2022 issue of Nebraska History Magazine.

Like every aspiring baseball player, Abbey had big dreams of making it to the major leagues. He started small, playing on semi-pro teams in Kearney and Beatrice, before securing a spot on a minor league team. However, with constant salary reductions and the market manipulation of players, the minor leagues at that time were unstable and did not yet provide a clear path to the majors.

For five seasons, Abbey jumped around teams—starting his 1891 season with the St. Paul (MN) Apostles and ending it with the Portland (OR) Gladiators—but that quickly changed after joining the Columbus (OH) Reds in 1892.

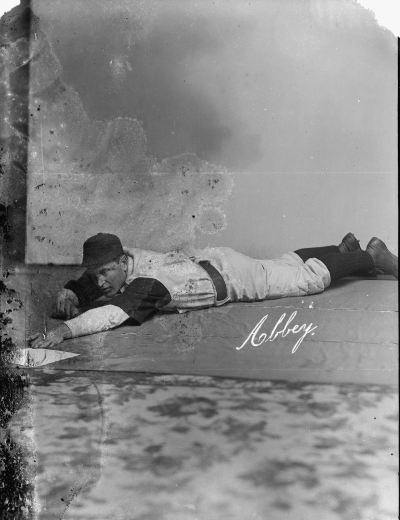

Pictured: “Charlie Abbey as a member of the Washington Senators baseball team, 1893-1897. One of a series of photos by Washington D.C. photographer C. M. Bell.” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Gus Schmelz, a baseball manager with a history of major league success, met Abbey as a player for the Reds and was impressed. Abbey didn’t have a great batting average, but his speed and strength in the outfield made him a player Schmelz would remember for his next managing job.

The two worked together to produce successful seasons for the Chattanooga (TN) Warriors. Then the Washington Senators’ new owner, Earl Wagner, offered Schmelz the manager’s job late in the 1893 season. Abbey made his major league debut on August 16.

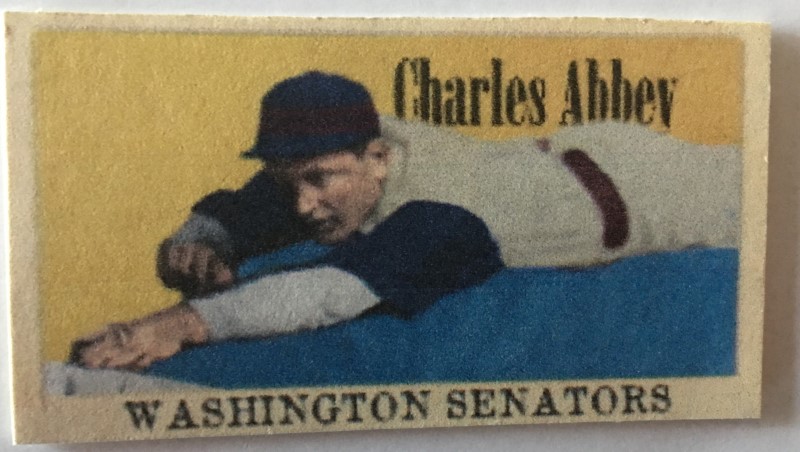

That August and September, Abbey played 31 games as the Senators’ left fielder. He batted .259, had a record of 9 stolen bases, and an outstanding .937 fielding average.

His debut reflected the same potential that Schmelz saw two years prior. The following season would be the best of Abbey’s career.

During his first full season he hit 7 homes run with an average of .314 – a record that made him one of only 33 Washington players to hit .300 before 1911. Scoring 101 runs batted in, stealing 31 bases, and splitting his time between center and left field, Abbey proved a strong asset to the team. His defense skills were so impressive that League President Nick Young called him “one of the greatest outfielders in the league.”

Abbey’s skill on the field gained him Wagner’s trust and respect, and made him one of the Washington team’s most popular players among fans, writers, and teammates.

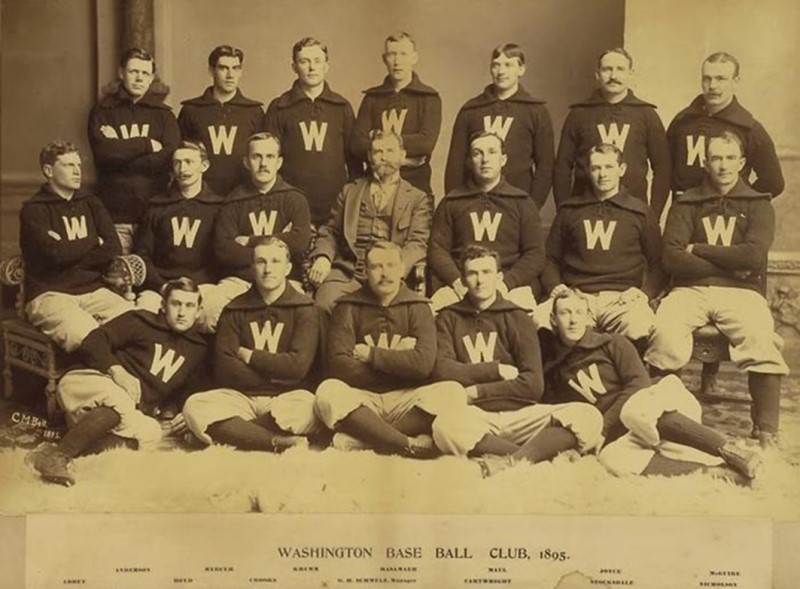

“The 1895 Washington Senators. The team never posted a winning season in the 1890s. Abbey shown far left and team manager Gus Schmelz at center.” Wikipedia

The 1895 season, however, would be the beginning of his decline.

Abbey’s significant decline in batting and fielding, and inconsistency put him at the bottom of the batting order. The public noticed his slump and wondered what had happened to the old Charles Abbey.

It wasn’t until August that his playing improved. Many papers, like the Star, wrote about his reemergence: “If Charlie Abbey had hit the ball throughout the season as he has been hitting it during the past six weeks, he would be up among the first dozen sluggers of the league.”

The 1896 season wasn’t much better. Abbey, who once reflected fielding strength, was now sharing his time in right field. He hit .262, made only one home run, stole 16 bases, and his fielding average dropped below .900 for the first time in his career. Despite these records, he managed some good plays.

Some of his catches that spring made reporters hopeful: “It was the old Charlie Abbey, he of 1894… his work established him firmly in the affections of the public.”

Abbey wasn’t the only one underperforming though, the team had a losing streak. Wagner, frustrated by the losses, bought a league in Toronto Canada, fire Schmelz as manager, and prepared to ‘clean house’ for the 1897 season.

After the game against Chicago on August 19th, Abbey was let go and ended the season on another team.

He played a total of 452 games over the span of a five-season career, which was typical for the time.

Unlike many players who struggled to cope with post-athletic life, Abbey appeared to handle it with grace. He stayed in D.C., was married, and worked at the Washington Post. But his life took a tragic turn in 1906.

On his way to work one January morning, Abbey was exiting a car on a busy street when he was knocked down by a passing vehicle. Landing in oncoming traffic, his arm was run over and had to be amputated just above the elbow.

Less is known about the last years of Abbey’s life. The 1920 census indicates that he moved to Seattle, was divorced, worked as an advertising solicitor, and lived in a boarding house. He died April 27, 1926, and was buried in Falls City.

Charles S. Abbey may not have been a Hall of Famer, but he encountered many whose were—such as Buck Ewing, who called Abbey the “best fielder in the country” in 1894.

“A studio portrait of Abbey was adapted for a baseball card.” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Abbey was also part of an important moment in baseball history, though he was on the losing side. Johnson writes, “1893 marked the first season with pitchers setting up at the modern 60’ 6” distance from home plate. Charlie’s debut featured a no-hitter by Baltimore pitcher Bill Hawk—the first delivered from the now iconic distance associated with baseball.”

The entire article can be found in the Spring 2022 edition of the Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues per year.