Starting in the high-wheel bicycle era, Lillie Williams of Omaha became a multi-sport professional athlete at a time when women’s sports were widely regarded as improper and physically harmful.

In 1889 an Omaha resident and novice female bicycle racer hurtled into the sporting spotlight. Starting in the high-wheel bicycle era, Lillie Williams became a multi-sport professional athlete at a time when women’s sports were widely regarded as improper and physically harmful.

Lisa Lindell tells Williams’ story in “The Nebraska Cyclone: Lillie Williams and the Embrace of Sport and Spectacle” in the Winter 2019 issue of Nebraska History Magazine.

Lindell describes Williams first race in Omaha:

“Over a period of six nights, before an overflow crowd averaging five thousand enthusiastic fans a night, Williams outrode the nation’s top “cycliennes” in a hotly contested race in the city’s newly constructed Coliseum. By the end, she had pedaled 259.4 miles and broken the women’s 18-hour cycling record. Although Williams would eventually take up and excel at a number of other sports—including motorcycling, swimming, and fencing, in which she set records and won championships—unrivaled in her memory was the race in Omaha that launched her professional career.”

Williams continued racing on an international women’s circuit. The races were held on indoor, banked velodromes similar to what modern track cyclists use. Cyclists switched to modern “Safety” bicycles within a few years, but wore no helmets. Like today’s competitors, they were sometimes seriously injured.

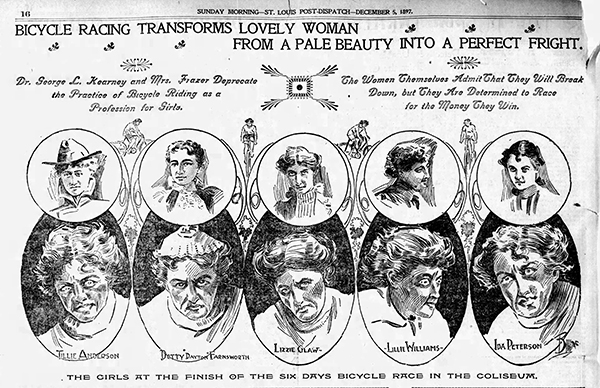

For this and other reasons, women’s professional sports remained controversial. This 1897 illustration from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch shows one of opponents’ biggest fears. (Williams is second from right.)

It wasn’t only the physicality of sports that opponents feared. It was also the fierceness of the women’s competitive drive. “They are riding for blood,” one newspaper reported.

The races drew cheering crowds and made money, but critics denounced them as unwomanly. Williams remained defiant. In press interviews, she boasted with cheerful swagger of her victories and her training regimen.

“I train just like a man preparing for a prize-fight,” Williams said in an 1897 interview. “I get up in the morning, punch the bag for ten minutes and then box for another ten minutes. Sometimes I wrestle and jump rope… and take excellent care of my general health.”

Williams later excelled in other sports, including motorcycle racing. After moving to Los Angeles, she made headlines when in 1912 she applied to join the police department’s motorcycle squad.

“Just set a speeder out in front of me and give me a chance at him on my motorcycle,” Williams said. “All I want is a chance to prove this.” But LAPD was not interested.

Incidentally, in 1912 Williams was still being judged for her looks, although not quite in the way the St. Louis Post-Dispatch would have predicted. That year an Omaha Bee reporter described the 50-year-old as “an attractive young woman.”

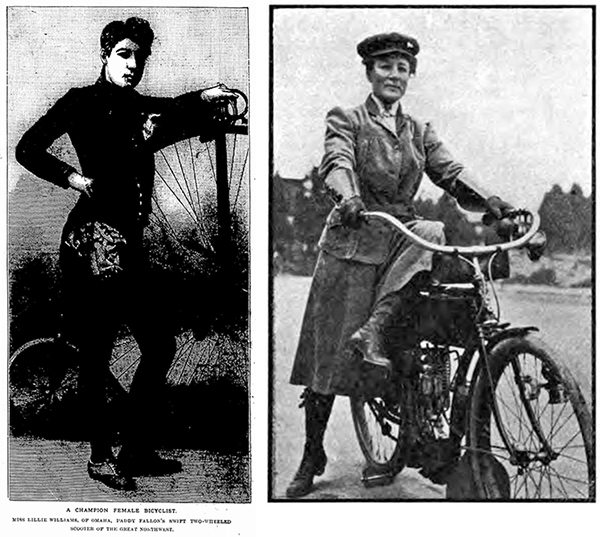

Photos at top of page: Lillie Williams in 1889 and 1912.

Read Lisa Lindell’s article (with many more photos) in Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues a year, and your membership helps support the work of History Nebraska.