In the 1850s, Nebraska was a newly-established US territory whose only towns lay along the Missouri River. Many of the new settlements were little more than “paper towns,” meaning that they had been platted and promoted but not yet built. Other settlements had high hopes but only a handful of residents. It wasn’t yet clear which towns would grow into cities, or even which would survive at all.

One well-to-do man set out to build a bustling commercial city near present-day Plattsmouth. Historian John Irwin tells the story of Oreapolis in the Fall 2020 issue of the Nebraska History Magazine.

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

In the 1850s, Nebraska was a newly-established US territory whose only towns lay along the Missouri River. Many of the new settlements were little more than “paper towns,” meaning that they had been platted and promoted but not yet built. Other settlements had high hopes but only a handful of residents. It wasn’t yet clear which towns would grow into cities, or even which would survive at all.

One well-to-do man set out to build a bustling commercial city near present-day Plattsmouth. Historian John Irwin tells the story of Oreapolis in the Fall 2020 issue of the Nebraska History Magazine.

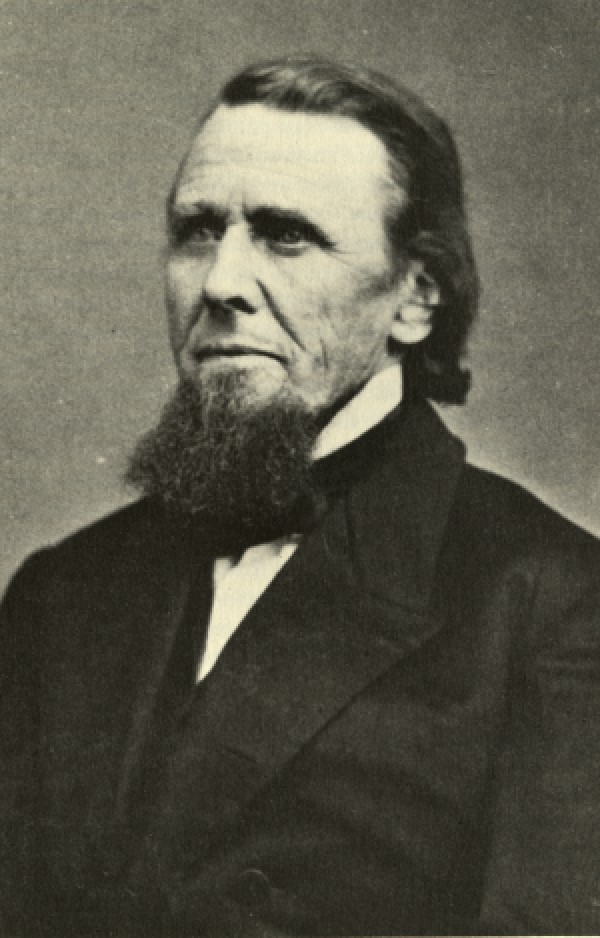

John Evans was already a wealthy and well-known man when he began planning Oreapolis. He had helped found Northwestern University, and Evanston, Illinois, was named in his honor. Many railroads were being built at the time, and there was talk of building a transcontinental railroad to California. In 1855 Nebraska’s acting governor, Tom Cuming, stressed the need to build the transcontinental railroad through Nebraska. Evans began to take an interest in the territory. He decided to build a city that would become territory’s main railroad city. He chose a location at the confluence of the Platte and Missouri rivers; the Missouri was full of steamboat traffic and the Platte Valley was a corridor for overland travel. There were already some towns in that area but it isn’t clear whether or not Evans feared competition.

John Evans was already a wealthy and well-known man when he began planning Oreapolis. He had helped found Northwestern University, and Evanston, Illinois, was named in his honor. Many railroads were being built at the time, and there was talk of building a transcontinental railroad to California. In 1855 Nebraska’s acting governor, Tom Cuming, stressed the need to build the transcontinental railroad through Nebraska. Evans began to take an interest in the territory. He decided to build a city that would become territory’s main railroad city. He chose a location at the confluence of the Platte and Missouri rivers; the Missouri was full of steamboat traffic and the Platte Valley was a corridor for overland travel. There were already some towns in that area but it isn’t clear whether or not Evans feared competition.

Evans’ idea was to jumpstart his new city by establishing a university and building the city around the concept of being a transportation hub. He intended to take full advantage of the public bonanza regarding the westward expansion and later, the Colorado gold rush.

“Evans was not exaggerating about the largescale design of his new city,” Irwin writes. The plat map included 276 city blocks with thousands of lots, and included a railroad depot, four public schools, and an “elevated hill land designated for its three core institutions”: the university, theological seminary, and high school. Considering the location and his own religious background, Evans advertised the new city mainly to Iowans and Methodists.

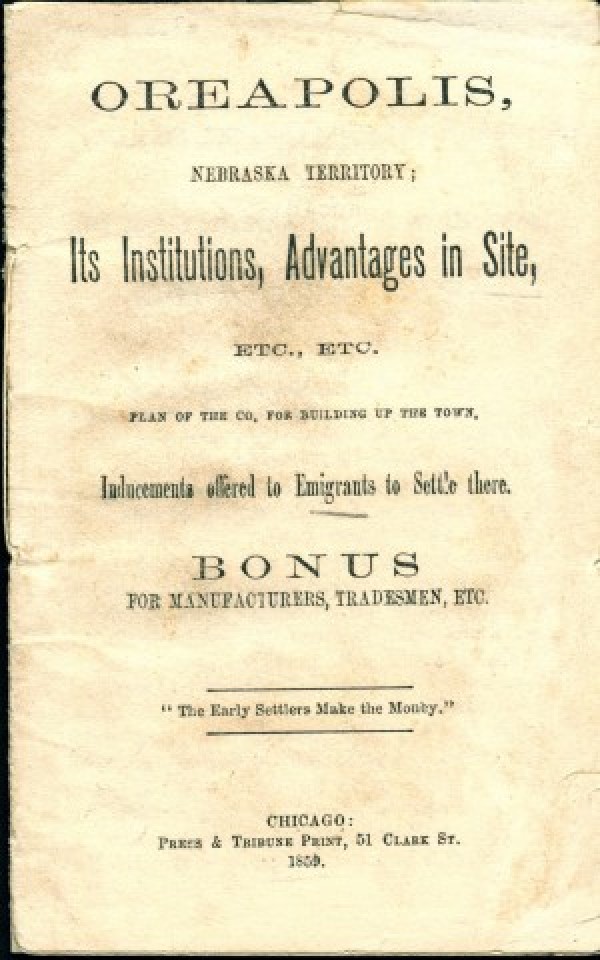

Not all of Evans’s plans went smoothly. In 1857 a worldwide economic crisis led to railroad bankruptcies, bank failures, and a halt to economic growth. Despite this, Evans thought Oreapolis would eventually succeed. He proceeded to buy and expand while prices were still low. In 1858, people ventured to the city’s site intending to buy lots and build during the fall and winter. With Evans’s influence, Oreapolis attracted the attention far beyond Nebraska. Chicago’s Press and Tribune touted the city’s potential and said that it would, without a doubt, grow into a “prominent commercial city.”

During this period, Evans published a prospectus entitled Oreapolis, Nebraska Territory, Its Institutions, Advantages. He elaborated on why Oreapolis would be “the most eligible route for a railroad”: extending toward the gold mines via the Great Salt Springs [present day Lincoln] and [the early] Fort Kearny. He also advertised the availability of natural resources locally and the one hundred miles of beautifully fertile, cheap land. The prospectus also offered bonuses for the establishment of businesses.

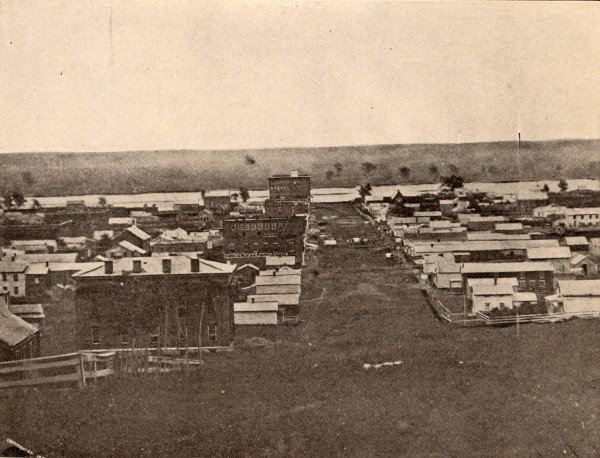

“Most importantly,” Irwin writes, Evans “assured readers that no one who [took] an unbiased view of the plan [could] fail to see in it the elements of a speedy success.” However, when Evans returned to the city in 1859, its population was only 187, far lower than he had predicted. In the meantime, surrounding towns such as Plattsmouth and Omaha had gained “economic and political influence,” which threatened Oreapolis’s future. Evans’s city was not succeeding and was facing financial difficulties. Evans believed that the delay of railroad construction in eastern Iowa was to blame.

Evans had many political connections, which he used to try to become Nebraska’s governor (territorial governors were appointed by the president). As governor, Evans would be in a position to favor Oreapolis. However, President Lincoln instead appointed him governor of Colorado Territory.

Eventually Evans cut his ties with Oreapolis and began directing his influence and wealth to Denver. He even began to favor Omaha as the location for the transcontinental railroad terminus, a betrayal of Oreapolis residents. The Methodist Conference withdrew its support of the Oreapolis seminary, which then closed.

Once the post office closed in 1864, the death of Oreapolis was final. By 1865 most of the town’s buildings were either moved to Plattsmouth or destroyed. After being open only three years, the seminary’s 8,000-square-foot building was demolished. The town’s last remaining building was the reverend’s residence, which stood until the 1940s.

Evans became devoted to Denver; Irwin writes that he “ultimately created the city that he had once intended twenty years before for Oreapolis,” making Denver one of the largest and most influential metropolises in the inter-mountain west.

Oreapolis may not have fulfilled John Evans’s dreams, but its story is a reminder of the many communities that rose and fell during Nebraska’s development. We can only wonder how things might have turned out differently if Evans had become Nebraska’s governor. What would this have meant for surrounding communities? Would Omaha have become another “sleepy Missouri River town,” Irwin asks. The answers are left to our imagination as we ponder the story of Oreapolis, “Nebraska’s Ghost City.”

Photos:

Top: Surveyed and Drawn by Gustave Seeger, the image is the Plot and Field Notes of Oreapolis in Cass County Nebraska Territory.

Middle: (As appears in post.) 1. Pictured is John Evans: born in 1814 to an Ohio Quaker family, died in 1897. 2. Omaha photographed in 1861 by A. Hospe. 3. Image of the prospectus for Oreapolis. (Chicago, IL: Press & Tribune Print, 1859)

The entire article can be found in the Fall 2020 edition of the Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues per year.

Categories:

Omaha, Plattsmouth, Cass County, ghost town, river town,