Railroad cars have been used to transport livestock since the 1830s, but until about 1860, the majority of shipments were made in conventional boxcars that had been fitted with open-structured doors for ventilation. Most railroads resisted the call for cars specifically designed to carry livestock, preferring to use standard boxcars because that type of car was more versatile. The suffering of animals during railroad shipping by hunger, thirst, and injury was considered to be unavoidable.

When the railroads and cattle industry failed to act quickly enough, the government and even the general public demanded change. In 1869, Illinois passed the first laws that limited animals’ time on board a train and required them to be given five hours of rest for every twenty-eight in transit. In 1870 the first patented livestock car designs (by Zadok Street) were used on American railroads. Other improved designs followed.

The Omaha Daily Bee on October 14, 1879, reported the presentation of information on “An Improved Car for the Transportation of Live Stock” to the American Humane Association, then meeting in Chicago. The Omaha inventors included wagon maker and blacksmith Charles J. Karbach. “The model for the car was presented to the society for the examination, by Mr. E. D. Pratt. It met with a very favorable reception, and the probability is that the proprietors of the invention will eventually make considerable money out of it, as it is destined to come into general use at no very distant day.

“The committee reported as follows: The size of the car is 8×30 feet in the clear. It contains a series of movable bars, so arranged that they may be moved up and down at pleasure through slatted standards. After the door is loaded, and the doors closed, the bars are let down from the outside between the animals, partitioning them off separately, or in pairs, as may be desired. The bars are raised from between the animals to the roof before unloading, when they are driven out in the ordinary way, and the car is left in a condition for returning freight.

“The car will accommodate sixteen steers, giving each animal a separate stall. Hogs may be partitioned off in like manner, with from fifteen to eighteen in each pen, thus preventing them from piling on each other and smothering. There is a tank underneath the car, with a capacity of ten barrels of water. This is connected with a pump on the roof of the car by means of which the water is forced through a perforated tube, which extends through the entire length of the car, completely filling it with a fine spray, which, when continued for a few minutes, amounts to a shower bath. This is designed to allay thirst and internal heat by being inhaled, and to allay heat fever and disease by keeping the pores of the skin open. . . . It is claimed that feed and water troughs may be attached to the car if found to be desirable at the conclusion of the experiments which are being made.”

Even after humane advances were put into common practice, many animals died in transit, further increasing the overall shipping cost. The ultimate solution to these problems was to devise a method of shipping dressed meats from regional packing plants to distant markets in a refrigerated boxcar.

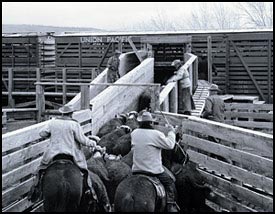

This view from the Nebraska State Historical Society depicts cattle being loaded onto a train.