The trial of William H. Irvine for the murder of Charles E. Montgomery in October of 1892 in Lancaster County District Court captured statewide (and national) attention. “The prominence of the parties, the wealth of the victim, the high character of the prisoner, the causes which led up to the shooting, and finally the sensational circumstances of the shooting itself, all combine to make the case most interesting and important,” said the Omaha Daily Bee on October 10, 1892.

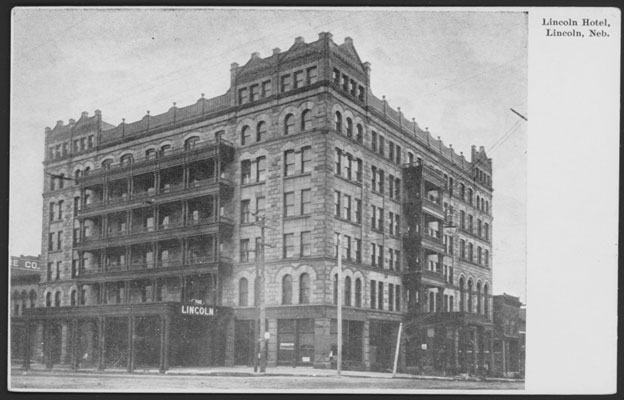

The crime for which Irvine, a Salt Lake City real estate man, was placed on trial for his life was the fatal shooting of Montgomery, president of the German National Bank of Lincoln. The crime occurred in the Lincoln Hotel on May 26, 1892, amid May 25-26 celebration in Lincoln of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Nebraska’s admission to the Union.

The Bee said: “The shooting occurred a few minutes before 8 o’clock [a.m.] in the dining room of the hotel. The room was crowded with guests of both sexes, and some of the most prominent people of Nebraska were quietly enjoying their morning repast, . . . Suddenly, without a word of warning, the report of a pistol shot rang through the room and then another. A gentleman sitting at the table nearest the door was seen to arise from his chair, stagger blindly around the table out into the corridor and fall at the foot of a divan.”

Irvine took Montgomery’s life because he believed that the latter had had an affair with his wife. At the time of the shooting Irvine had in his possession a signed statement in which the wife admitted her relationship with Montgomery. Irvine was taken into custody after the shooting amid a crowd of excited spectators.

When the case went to trial in October 1892, Irvine’s lawyers, according to the Bee on October 14, “set up in defense of their client the plea of . . . mania transitoria.” Irvine took the stand in his own defense and had his eight-year-old daughter, Florence, present in court. A number of witnesses attesting to his good character appeared, and depositions from acquaintances in Salt Lake City (and from Arthur L. Thomas, governor of Utah Territory) were introduced as evidence.

The prosecution, said the Bee on October 25, “denied that the prisoner was laboring under temporary insanity, and contended that if Irvine had been a poor man, without means to employ from twelve to fifteen attorneys for the purpose of working up a sentiment in his favor, the jurors would not find it necessary to leave their seats to find a verdict of guilty.” The defense, while not disputing that Irvine had shot Montgomery, appealed to the jury for a “verdict that was based upon a higher law than that found in the statutes.”

The verdict–not guilty–was not long in coming and seemed popular with trial watchers. “Everybody seemed to be in a congratulatory mood. People shook hands with the jurors, with the bailiffs, with the attorneys and with each other.” Irvine returned to Salt Lake City, where it was reported that his friends “were preparing to give him a big reception on his arrival home, and [that] he would be met at the depot with seven brass bands and 5,000 torches.” It was March of 1895, however, before bitter divorce proceedings between Irvine and his wife were concluded, allowing both to drop from public view.

The Lincoln Hotel at Ninth and P streets was the scene of a sensational murder in May of 1892. NSHS RG2158-408c