By David L. Bristow

“I once was in bondage,” Robert Ball Anderson writes in his 1927 autobiography, From Slavery to Affluence, “… owned but owning nothing, valued in dollars and cents as any other chattel, to be bought and sold, traded or worked, even as a horse or cow, as the financial needs or desires of the owner dictated.”

That’s how it was for the first 21 years of Anderson’s life. “But now I am a free man, a citizen of the United States, a property owner, and boss of my own ranch.”

Anderson’s long journey–from Kentucky to Nebraska, and from slavery to wealth–is in some ways a story of persistence and personal triumph, and in other ways a demonstration of the obstacles he faced in trying to become truly independent.

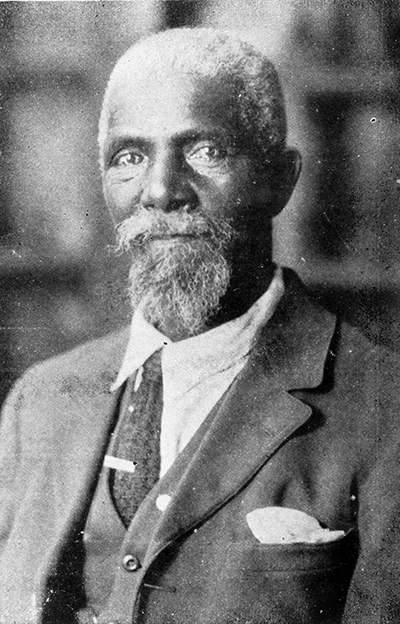

Robert Ball Anderson, from his autobiography. History Nebraska RG2973-2-2

* * *

Anderson was born a slave in Kentucky in 1843. His earliest memories were of log cabins, one-room huts where the slaves were housed “pretty much as pigs in a pen.” The master, he writes, was not deliberately cruel. “It was merely the custom of the times, when it was thot that the colored race needed no more care than a hog or cow, and got considerably less than a horse.”

The master’s wife was cruel. When Anderson was six, she had his mother sold to a slave trader. He never saw his mother again. On another occasion, the mistress tied Anderson and beat him nearly to death with a rawhide whip. The sores on his body took a long time to heal. “The sore in my mind,” he writes, “has not entirely healed yet.”

It was one of these unjust beatings, one of the many that left his body looking “like a board that is full of knots,” that led Anderson to consider running away. He was 21. The Civil War had entered its fourth bloody year, and a Union army recruiter was said to be just 20 miles away.

But instead of running, Anderson went to his master and told him his intentions. At first the master was angry, but in the end agreed to let Anderson go. Perhaps he felt that the war was all but lost and slavery doomed –– Anderson doesn’t say. “We had quite a talk, and parted friends,” he writes.

* * *

The war ended six months later, but Anderson’s enlistment ran for three years. He was sent west to Indian country, and served as an infantryman from Kansas to New Mexico. He saw a lot of land during his army days, and began thinking of getting some of his own. “It is to that determination, formed when a soldier” he writes, “that I owe my independence today.”

Using the army pay he had carefully saved, he bought some western Iowa land sight unseen from a real estate agent in Davenport. He was swindled. The land was poor, and Anderson had to sell at a loss. He then found work at a brickyard to earn more money.

Anderson came to Nebraska in 1870, taking a homestead in Butler County. Anderson said it was the first Nebraska homestead claimed by a Black man.

The farm was not a success. Within a few years, “I lost this land thru crop failure. One year the grasshoppers came and ate up everything. Then came four years of drouth when everything burned up… I lost everything I had, and in 1881 I went to Kansas and worked in a railroad construction camp as a cook.”

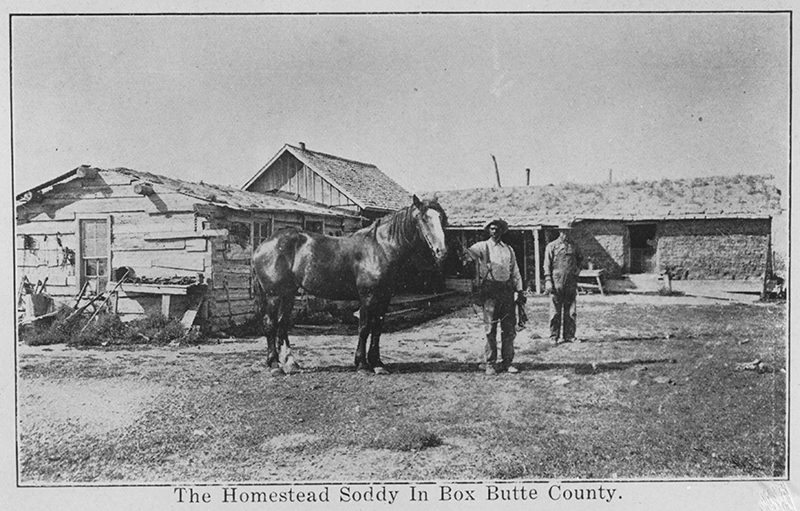

The 38-year-old Anderson was not ready to give up. Quitting the railroad, he worked three years as a farm hand in Kansas, saving his money. Then he returned to Nebraska, this time to Box Butte County in the Panhandle. He built a sod house, adding a log cabin later, and then spent three years in eastern Nebraska as a railroad cook, saving his money as always.

When he had accumulated $1,600 –– a considerable sum in those days –– he decided to invest to build capital for his farm. He loaned the money at interest, but the borrower took the money and left the state. Once again, Anderson was broke. To work his farm, he had to take out a loan himself, and spent the next ten years repaying the debt. “I lived alone,” he writes, “saved, worked hard, lived as cheaply as I could, and before long I found that I had some money to put in the bank.”

The GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) was an association of Union Army veterans of the Civil War.

* * *

At last, Robert Anderson began to prosper. Now and then, he took time off to travel, visiting Cuba and Mexico and most of the United States. He finally married at age 79. His bride, a 21-year-old schoolteacher named Daisy Graham, helped him write his memoirs. They were married eight years before Anderson died in a car accident in 1930 and is buried at Hemingford Cemetery. He was 87.

His widow was 29. When she died in 1998 at age 97, Daisy Anderson was one of only three surviving Civil War widows. A woman living in the 1990s was the widow of a man who had once been enslaved by a veteran of the Revolutionary War.

Anderson’s cabin in 1966. Decades later, the dilapidated cabin was on the verge of collapse before it was moved and rebuilt in 1995 for display at Dobby’s Frontier Town in Alliance. RG2973-1-14

* * *

In some ways, Anderson’s experiences were typical of enslavement –– the beatings and humiliations, the separation of families, the struggle to find a livelihood and real independence in the post-emancipation years. But in other ways his story is remarkable. Most Great Plains settlers failed and went back East, usually done in by drought or other economic hardships. Anderson overcame all the usual obstacles in addition to the artificial ones created by racial prejudice.

“I belong to the black race and am not ashamed of it,” Anderson writes, noting that his parents were both “pure blooded African Negros and there is not a drop of white blood in my veins.”

Anderson’s eventual prosperity came at tremendous personal sacrifice. He lived most of his life alone. During the years Anderson worked for wages, could he have saved money if he’d had children to feed?

“I have a good farm,” he writes near the conclusion of his memoir, “well stocked with plenty of horses, cows and farming machinery, with shade trees, fruit trees, grapes, berries, and have money in the bank to tide me over my old age when I am unable to earn more. A slave at the age of twenty, penniless at the age of forty-five, I am a rich man today.”

Sources:

Robert Anderson, From Slavery to Affluence; Memoirs of Robert Anderson, Ex-Slave (Steamboat Springs, Colorado, 2nd ed., 1967).

Darold D. Wax, “Robert Ball Anderson, Ex-Slave, A Pioneer in Western Nebraska, 1884-1930,” Nebraska History 64 (1983): 163-192.

“Robert Ball Anderson, 1843-1930 (RG2973.AM),” Nebraska State Historical Society Finding Aid.

(Posted February 1, 2023)