The namesake of Sarpy County, Peter Sarpy (1805-1865) was an important trader whose career spanned Nebraska’s fur trade and territorial periods. “Sarpy’s life is not easy to chronicle for he became a legend in his own time,” writes historian John Wickman.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

The namesake of Sarpy County, Peter Sarpy (1805-1865) was an important trader whose career spanned Nebraska’s fur trade and territorial periods. This 1852 portrait by St. Louis artist Manuel Joachim de Franca is part of the Nebraska History Museum collections.

“Sarpy’s life is not easy to chronicle for he became a legend in his own time,” writes historian John Wickman.

Sarpy was born to a French Creole family, probably in St. Louis. His early life is poorly documented, but it appears that at age 19 he traveled up the Missouri River to present-day Nebraska. He worked at the American Fur Company’s trading post near Bellevue. The company brought manufactured goods upstream by keelboat, traded for furs with local Native tribes, and sent the furs back to St. Louis. Later he operated his own trading post, eventually trading with white settlers arriving in the area and operating ferries across the Missouri, Elkhorn, and Loup rivers.

Young Sarpy was known for his fierce competitiveness, and was loyal to his employer, John P. Cabanne. Acting on Cabanne’s orders, in 1832 Sarpy and others illegally seized a competitor’s keelboat. The action got Cabanne and Sarpy temporarily kicked out of the territory. Sarpy spent time in Colorado and returned home to St. Louis for several years.

Court documents digitized by the St. Louis Freedom Suits Legal Encoding Project reveal what today is the most shocking chapter of Sarpy’s life. While in St. Louis, Sarpy owned a slave named Andrew. But Andrew was legally a free man. In 1839 Andrew’s mother, Celeste (also legally free), appeared court on Andrew’s behalf to sue Sarpy for trespass and false imprisonment. The complaint alleged that Sarpy had “with force and arms assaulted the said plaintiff… and beat and bruised and ill treated him and then and there imprisoned him….” Andrew feared that Sarpy would take him out of Missouri, where, presumably, it would be even more difficult to prove his free status. By then Sarpy had already built another trading post at Bellevue.

Sarpy disputed the charge and the case dragged on until February 2, 1841, when the court found Sarpy guilty, freed Andrew and (presumably) awarded the $200 in damages Andrew had sought.

Back in Nebraska, Sarpy became known for his ability to gain the respect of Native tribes in the region. He was in contact with tribes within several hundred miles of Bellevue. Like many fur traders, he married a Native woman. This certainly helped solidify his trading relationships, but it seems to have been more than just a strategic union—Peter and Nicomi remained married for the rest of Sarpy’s life.

As a businessman, Sarpy adapted to changing times. By the 1850s he was operating a ferry across the Missouri River, serving a growing number of emigrants heading west along the trails. In 1854, the year Nebraska Territory opened to Euroamerican settlement, Sarpy bought a 165-ton steam ferry and played a prominent role in negotiating land cessions by the Omaha and Oto tribes. In 1857 the Nebraska legislature named Sarpy County in his honor.

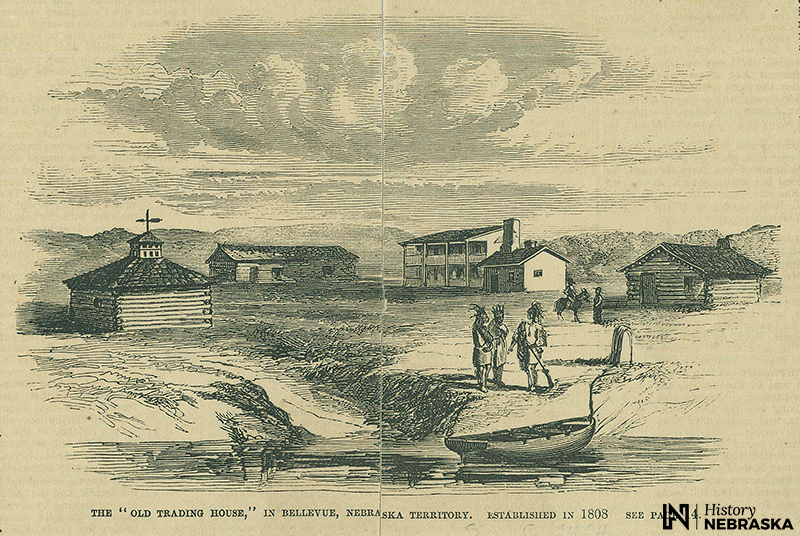

Illustration: Bellevue, Nebraska Territory, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 5, 1858. Contrary to the caption, there is no evidence that the Bellevue trading post existed prior to 1823.

“Sarpy lived the life of a minor frontier baron,” writes John Wickman, who says Sarpy was known for his hospitality and for his love of “fast horses, fine hunting dogs, and a considerable interest in the pleasures of liquor.”

Throughout his life, Sarpy cultivated a reputation for both generosity and ruthlessness. Missionary Samuel Allis described him in ways that reveal as much about the time and place as about the man himself. Allis said that Sarpy, “although sometimes rough and uncouth, was a high-toned gentleman, who exerted a great influence among the whites as well as the Indians. He was particularly generous to white men of distinction and wealth, also to the Indians when it paid well, but exacted every penny of his hired men and others who earned their living by labor. Still he was generous to the needy… He was all that could be wished for a man of the world, except the habit of intemperance.”

These sources say nothing about Sarpy’s 1841 conviction for false imprisonment. Perhaps the story didn’t follow him out of Missouri. (I didn’t know about the case myself until a reader pointed it out after seeing an earlier version of this post.)

Peter Sarpy died in Plattsmouth in 1865. His body was returned to St. Louis for burial, but it’s said that his wife Nicomi remained in the Plattsmouth area.

Illustration: This 1894 oil painting by Ad Albrect is based on an 1850s sketch by Stanislas Schimonsky. It shows Bellevue near the end its trading post days, but the Missouri River bluffs seem to have grown to legendary proportions in the retelling—much like Sarpy himself. History Nebraska 300P

The 1852 portrait of Sarpy at the top of this page is shown after its 2011 restoration by paintings conservator Kenneth Bé at History Nebraska’s Gerald R. Ford Conservation Center.

Last updated 6/16/2020.

Sources:

“Andrew by next friend vs. Peter Sarpy, in St. Louis Cir. Court, July November Term 1839,” The St. Louis Freedom Suits: Legal Encoding Project, Washington University, http://digital.wustl.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ccr;iel=4;view=toc;idno=ccr1839.06838.012.

Larsen, Lawrence H., Barbara J. Cottrell, Harl A. Dalstrom, Kay Calamé Dalstrom, Upstream Metropolis: An Urban Biography of Omaha & Council Bluffs (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 24.

Jensen, Richard E., The Fontenelle & Cabanné Trading Posts: The History and Archeology of Two Missouri River Sites, 1822-1838 (Lincoln: Nebraska State Historical Society, 1998).

“Pilcher, Fontenelle and Sarpy,” NebraskaStudies (NET, History Nebraska, Nebraska Department of Education), http://nebraskastudies.org/1800-1849/fur-traders-missionaries/joshua-pilcher/

Wickman, John E., “Peter A. Sarpy,” in LeRoy R. Hafen, ed., The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Vol. 4 (Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1966), 283-96.