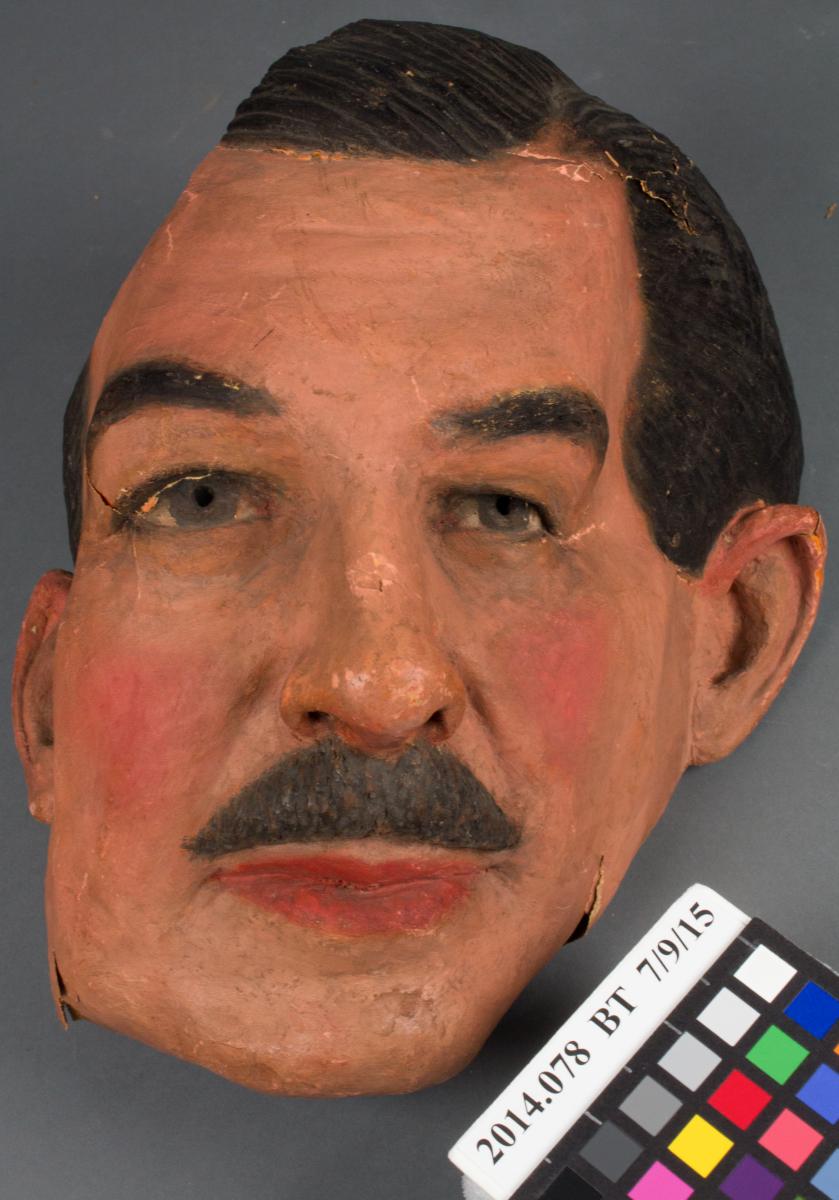

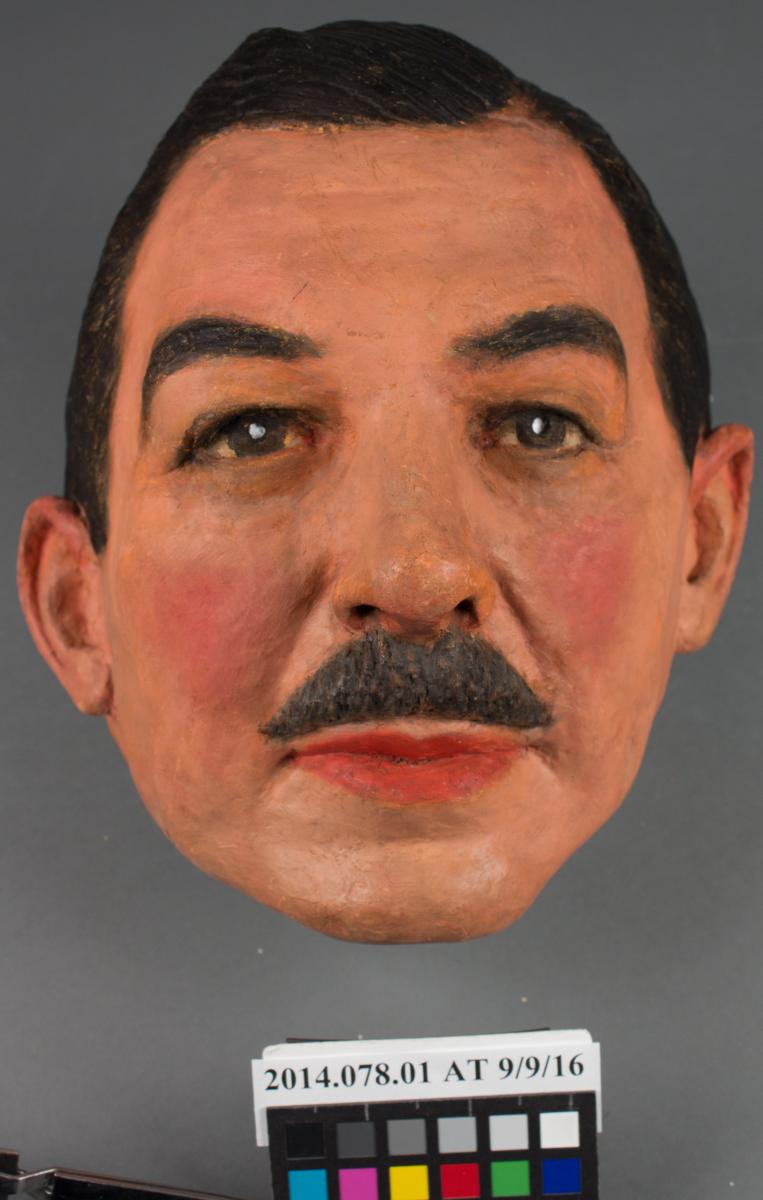

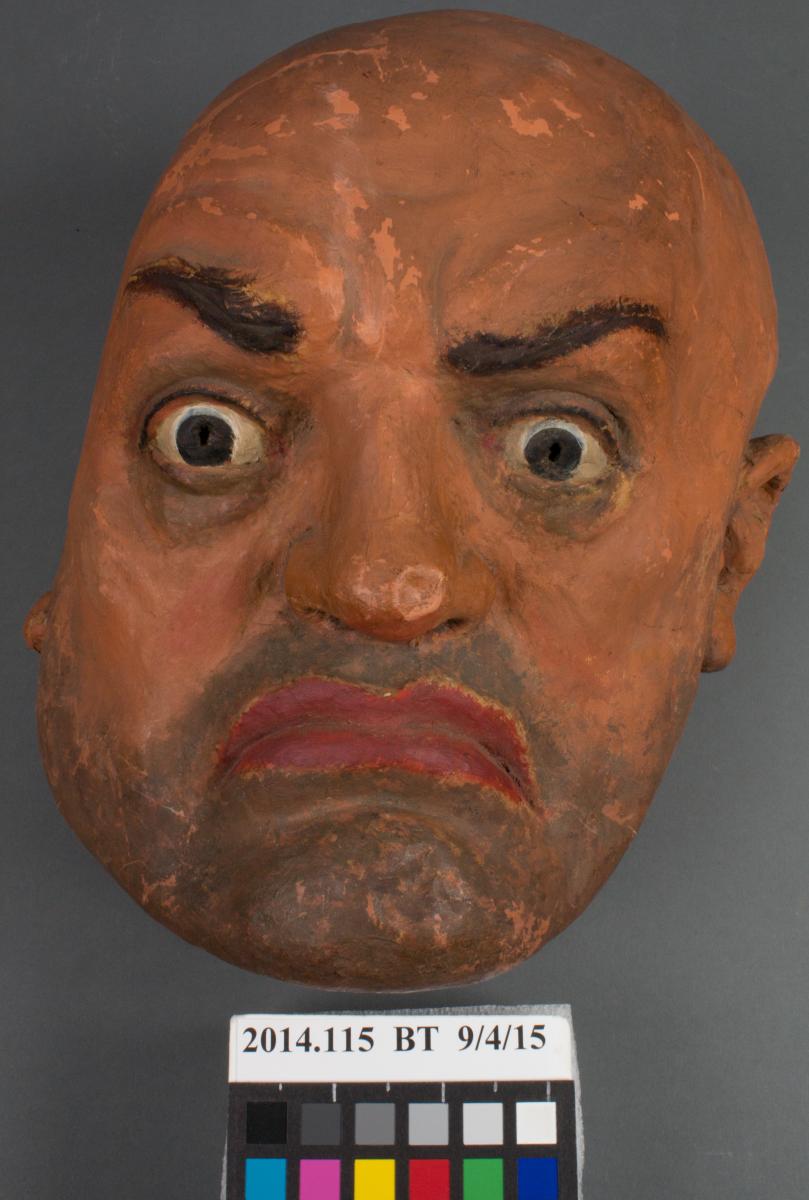

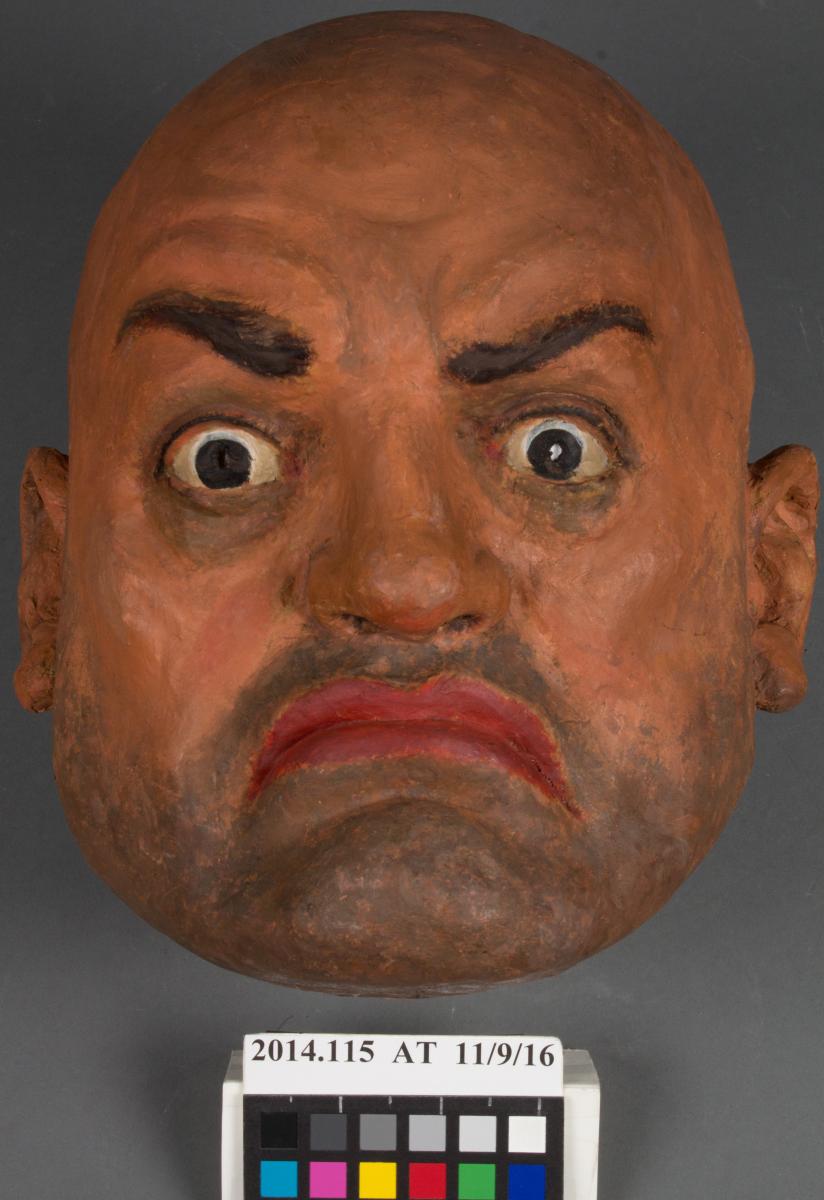

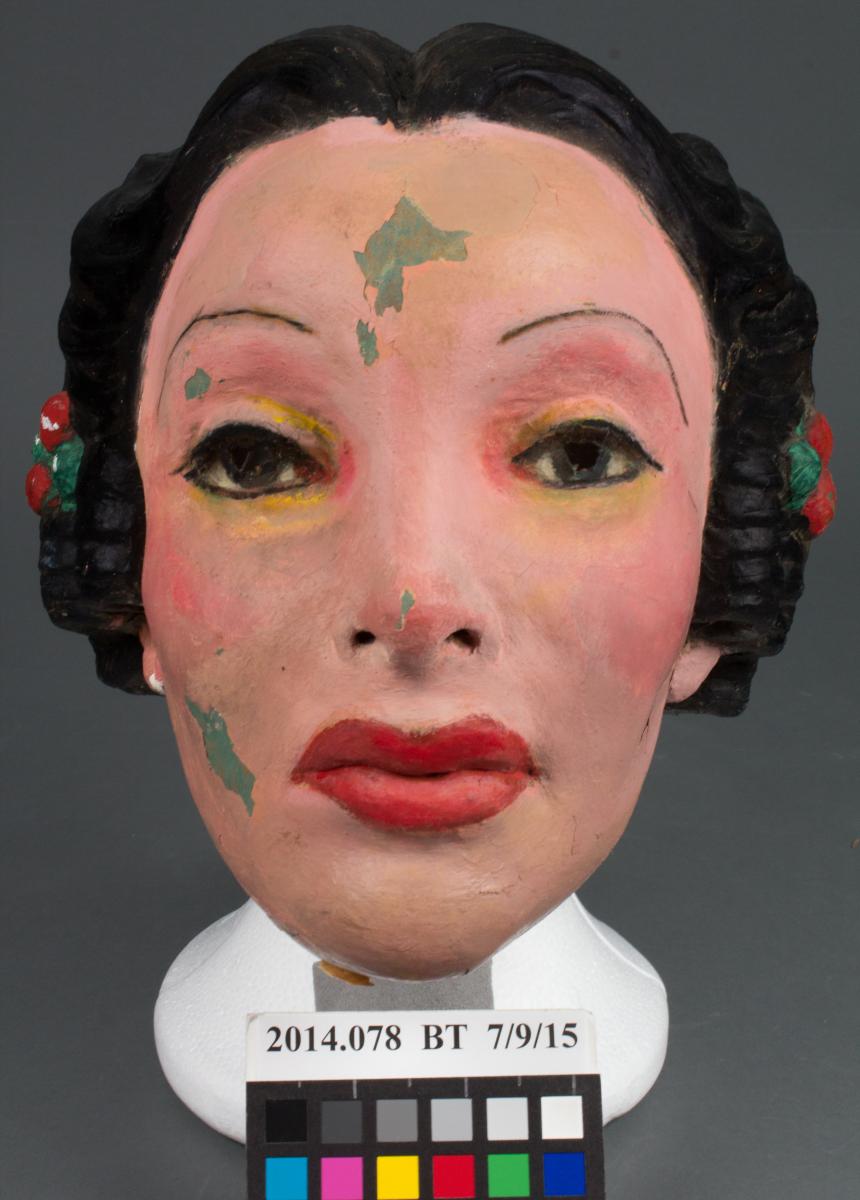

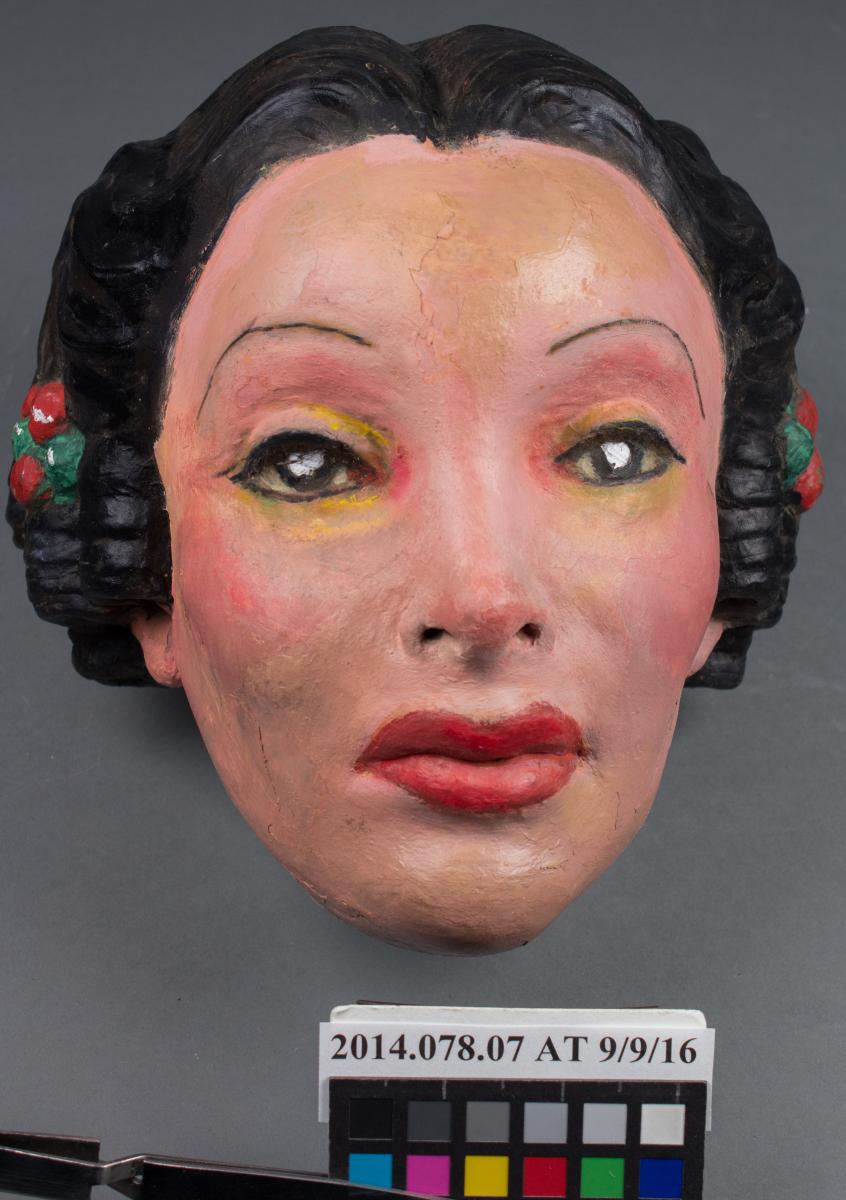

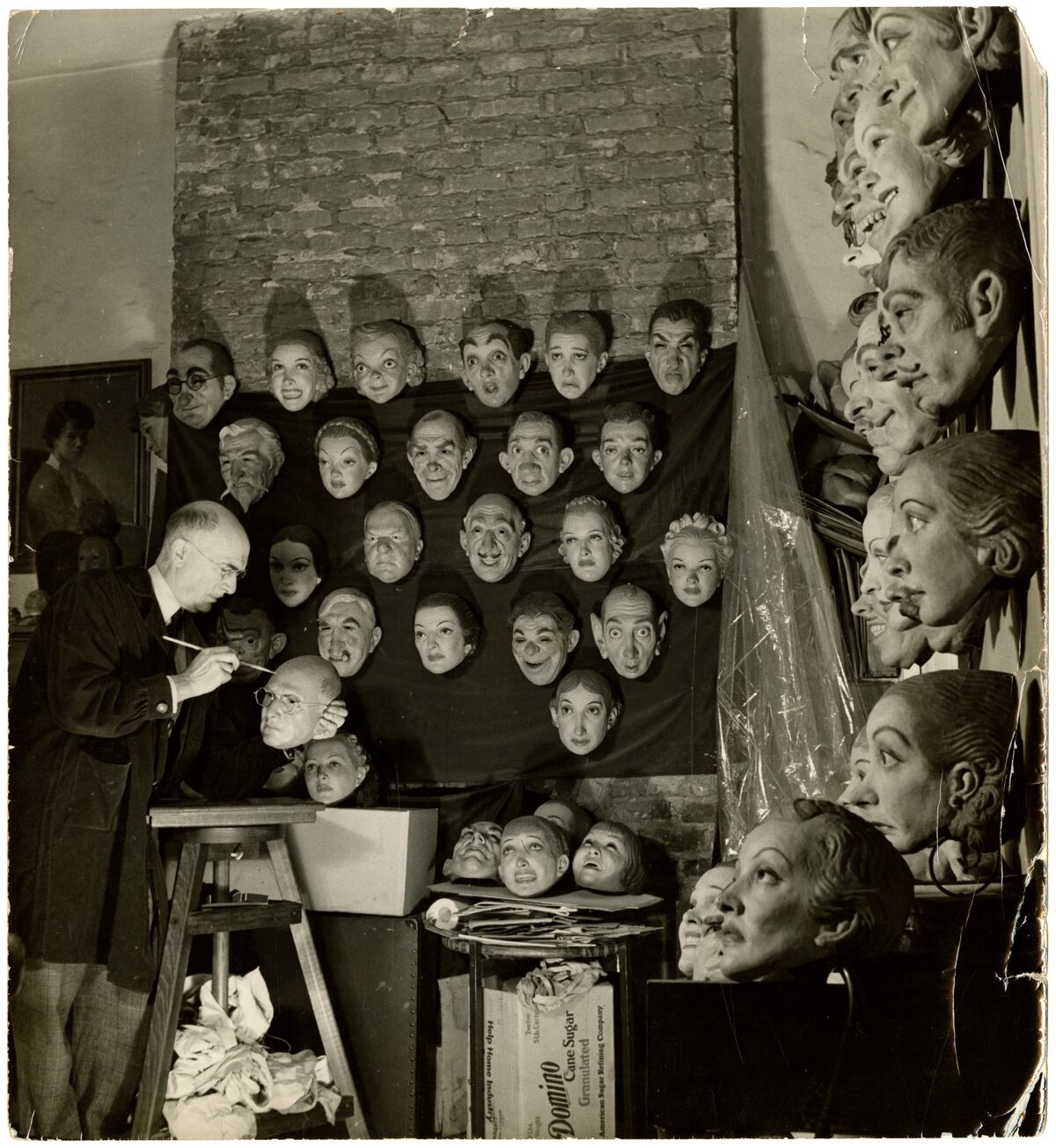

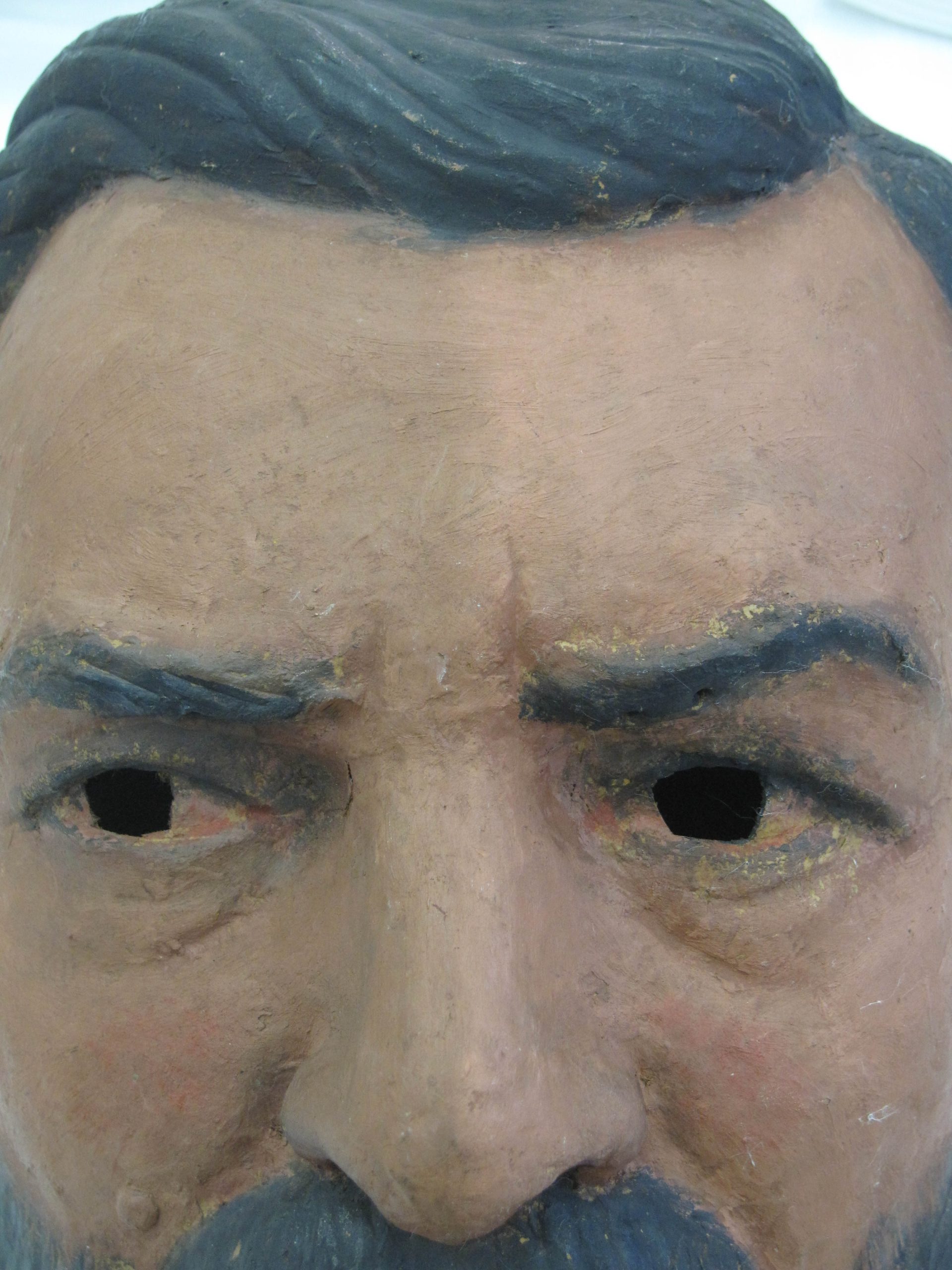

Unusual objects have a way of showing up for treatment at the Ford Conservation Center. So in some ways the 69 masks by Nebraska artist Doane Powell were no surprise. But a little bizarre? Maybe. The Nebraska History Museum collection of mid-20th century faces, both famous and infamous, were made from a wide range of materials–including leftover lingerie! Fortunately Powell left a detailed book on how to make masks, complete with step-by-step instructions and diagrams. He described himself as a “Cartoonist. Portrait Painter. Sculptor. Art Instructor. Art Director. Lecturer.” Powell had many talents, but conservator he was not. His wide range of layered paper masks were widely used for social events, theater productions, advertising, masquerades and early tv shows. The daughter of Powell’s assistant donated them to the Museum and the staff brought them to the Ford Center for treatment as the evidence of their use was clear. 60+ years of hand grime and environmental residue were obvious. Ears and noses were damaged or missing. Layers of paint were flaking and fading. Conservators had a lot of testing to do, but they were sure they wouldn’t follow Powell’s bad advice: “As in oil painting, one of the best methods of cleaning is to cut a raw potato and rub the cut side over the surface.” (PLEASE NOTE: Do not clean your masks or oil paintings with a raw potato, or potatoes of any kind! Please consult a conservator instead!)

The Ford Center staff approached this project like we do every other one: 1) What can we do to stabilize the piece, to ensure it is structurally sound and to prevent further damage? 2) How can we best clean the surface? 3) What can we do to compensate for any aesthetic damage and return it to closer to its original intended appearance? In this case, we examined each of the masks and came up with a general many-step treatment plan:

- consolidate any loose paint or fragments

- vacuum the masks with a brush and a net over the nozzle, just in case any pieces came loose

- clean the surfaces, testing the paint surfaces and using extreme caution so as not to disturb the original materials

- humidify warped masks either locally or in a humidification chamber

- mend and fill tears or losses

- inpaint repairs to visually integrate with the surrounding area.

These “face lifts” took many hours. A final question: how best to support the masks for transport back to the museum, for exhibition and eventually their long-term storage. A clever combination created a support for all three purposes. Step one: trim a generic Styrofoam head to size. Step two: make a pillow for each mask from Tyvek and stuff with polyester batting. Step three: gently press the pillow to support any cavities inside the mask. Masks ready to travel, go on exhibit, and rest in storage. Museum staff covered the supports with black cloth for dramatic display in the exhibit, “The Strange and Wonderful Masks of Doane Powell” at the Nebraska History Museum now through July 9, 2017.

While we encounter history every day in our jobs, it is not every day that we come face-to-face with it. This project was a group effort for the staff that proved as fun as it was challenging.