In a land of open fields and apple pie, Southeast Nebraska seemed calm and routine. But in 1958 construction began on a project that was quite the opposite–giant underground bunkers holding long-range Atlas missiles for U.S. defense during the Cold War. In the Summer 2012 issue of Nebraska History, Nicholas Batter reveals the fascinating role Nebraskans played in the arms race.

Although small town Nebraska seemed far from the conflict, nuclear war makes front lines of the whole world. On top of that, proximity to Strategic Air Command (SAC) at Offutt Air Force Base made eastern Nebraska sites ideal. Were the Soviets to attack, SAC would coordinate retaliatory strikes immediately.

Workers prepare an Atlas missile for a suborbital test launch at Cape Canaveral, Florida, on September, 17, 1959.

Starting in 1958, nuclear-armed Atlas missiles were assigned to several U.S. Air Force Bases, including Offutt and Lincoln AFBs in Nebraska. The year 1958 saw a serious economic recession in the United States. Tens of thousands were unemployed in Nebraska, and the lack of work meant a warm welcome for the government project. Thousands of workers were required to keep construction of the massive missile bases on schedule. Even with long hours and extended work weeks, workers from surrounding neighborhoods were brought in to help with the project.

In Saunders County, the missiles soon meant more than jobs for the towns of Mead and Wahoo. They came to mean patriotism, protecting one’s country, and the opportunities of a new age. The county fair that summer had numerous parade floats featuring homemade rockets.

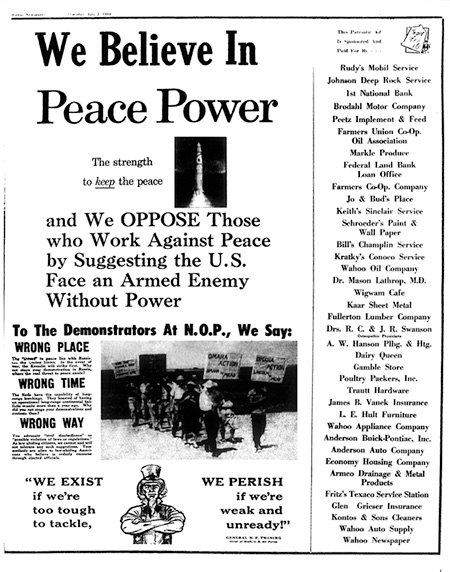

Local support for the project was so great that when out-of-town peace protesters arrived in 1959, local residents rallied against them. The pacifists called themselves “Omaha Action,” and set up a camp outside Mead’s missile base. Their signs boasted phrases such as “End the Missile Race, Let Mankind Live” and “Omaha Action Nonviolence Against Nuclear Missile Policy.” Newspapers described the protestors as “educated, quiet, [and] sincere about [the] project.”

One of the activist leaders wrote: “we believed that contrasting our belief in nonviolent resistance with SAC’s belief in military force and nuclear deterrence would be dramatic and thought-provoking.”

Dramatic was an understatement. The local people saw the group’s very presence as an attack on their livelihood and patriotic spirit, and responded harshly with newspaper articles and counter-protests. Omaha Action members were arrested for acts of civil disobedience and often treated worse than other prisoners while in jail. And ironically, by trying to stop the missile base, the protestors only seemed to have the effect of increasing local support for the base as the community rallied around it and viewed it as their contribution to the Cold War.

Fortunately, the Atlas missiles were never launched. Several years later, a new generation of missiles replaced the Atlas, leaving the giant underground silos empty. Southeast Nebraska’s participation in the Cold War faded from memory as western Nebraska became known for its Minuteman missile sites. However, the Atlas project provided communities with an economic boost, brought about America’s first generation of missiles, and in hindsight teaches us about the concerns and attitudes of the Cold War.

-Joy Carey, Editorial Assistant

Read Nick Batter’s complete article, “The Shoulders of Atlas: Rural Communities and Nuclear Missile Base Construction in Nebraska, 1958-1962” (PDF)