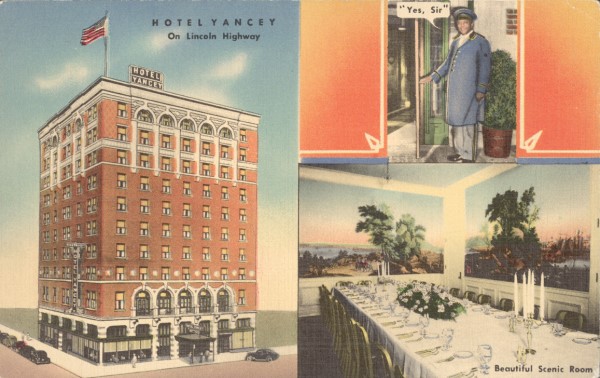

A 1940 postcard tells multiple stories about Grand Island and mid-20th century America. The building itself remains a local landmark, while the postcard tells us about travel, small-town ambitions, and racial views.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

This 1940 postcard tells multiple stories about Grand Island and mid-20th century America. The building itself remains a local landmark, while the postcard tells us about travel, small-town ambitions, and racial views.

Grand Island was a small but rapidly growing city in the 1910s, though it was only a fraction of its current size. It grew from 10,300 residents in 1910 to nearly 14,000 in 1920.

The “Hotel Yancey,” as it styled itself, was Grand Island’s premier hotel for many years. Construction began in 1917, during the height of the passenger rail era. Auto travel was in its infancy, and Grand Island was located along both the Union Pacific Railroad and the new Lincoln Highway.

Plans called for a 150-room, 11-story hotel featuring the latest in high-rise architecture. It was to be part of a chain of first-class hotels operated by the North American Hotel Co. (North Platte’s Pawnee Hotel was also part of the project.)

The building began to rise above downtown Grand Island—and then stopped abruptly in 1918 due to financial difficulties and World War I shortages of labor and materials. The building stood as an embarrassing half-finished skeleton for five years before new investors took over.

When it opened in 1923, the Hotel Yancey featured amenities such as a ballroom, party and banquet rooms, public bath house, pharmacy, coffee shop, cigar shop, barber shop, billiard room, laundry, and other amenities. Its restaurant offered truffles, caviar, and calf brains, and hotel guests were greeted by doormen and bellhops. This was how to travel in style. One didn’t have to forgo big-city amenities even in the heart of Nebraska.

***

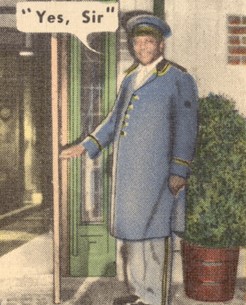

And that was the point of picturing the Black doorman with a “Yes, sir” word balloon. It showed that this was a classy place.

By why were Black doormen and bellhops a thing?

The idea that it was fine thing to be waited upon by African Americans went back to slavery, of course, but post-Civil War history is also important. When George Pullman introduced his luxurious sleeper cars for railroads, he hired formerly enslaved people to staff them. Partly this was to reduce labor costs—because people will work cheap when they have few other employment options besides field labor—and partly it was because having a Black house servant was already an icon of American wealth. Pullman wanted to give passengers the experience of being treated like plantation aristocracy.

Pullman’s scheme was so successful that Pullman porters were exclusively Black into the 1960s, and high-class hotels and other establishments followed suit. The uniformed, smiling, unfailingly polite and obliging Black porter, doorman, or chauffer, became a luxury item for White people during the worst years of racial segregation.

This is one of the ironies of “segregation.” It was never about keeping people separate. As the smiling doorman illustrates, African Americans were welcome to be in close contact with White people in railcars and hotels, as long as they were present in servile roles. Segregation banned proximity only under circumstances that implied equality.

And yes, Nebraska was segregated. Not as blatantly or completely as southern states, but housing and employment discrimination were rampant, and many businesses violated state anti-discrimination laws with impunity. There is no reason to think that the Yancey would have welcomed African American travelers any more than Omaha’s Hotel Fontenelle did at that time. (Some years ago, Omaha musician and bandleader Preston Love Sr. told me that traveling Black orchestras had to stay in Black-owned boarding houses because they were not allowed in Omaha hotels—even famous artists such as Count Basie. The only exceptions Love could recall were Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway, though Love recalled Ellington having to take his meals in his room while staying at the Fontenelle.)

While the Nebraska section of the 1940 Negro Motorist Green Book may not be comprehensive, it’s telling that the listing of Black-friendly lodging fills less than a page, and includes no Grand Island entries.

All that said, the story of the Black doorman is also an example of African Americans making the most of an unjust situation. Because of employment discrimination, jobs as Pullman porters or hotel bellhops were among the best available to Black men, and having such a job brought a measure of respect. “They became in many ways the middle-class of the African-American community,” historian Spencer Crew told Smithsonian Magazine.

***

The Yancey ushered in Grand Island’s “golden age of hotel opulence,” writes Mark Coddington in the Grand Island Independent. The hotel went bankrupt during the Great Depression and was closed from 1931 to 1933 before reopening under new ownership. As the postcard shows, it had resumed its glory by the time of World War II.

But the golden age began to fade within a few decades. Motor travel siphoned off railway passengers, and new “motor hotels” (soon contracted to “motels”) sprung up on the edge of town. And then Interstate 80 drew motorists away from the city entirely.

The Yancey closed in 1982. Today the building at 123 N. Locust holds offices and condominiums. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Until a few years ago, it remained the tallest building in Grand Island.

(Photos: History Nebraska RG3451-3-149; RG3451-3-15)

(Posted 2/1/2021)

Update, 2/3/2021: Thanks to the Plainsman Museum in Aurora, Nebraska, we’ve learned the doorman’s name and personal story. Read Part 2 here.

Sources:

Blakemore, Erin, “Five Things to Know about Pullman Porters,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 30, 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/five-things-know-about-pullman-porters-180959663/

Bristow, David L., “Swingin’ with Preston Love,” Nebraska Life Magazine (September/October 1999). https://davidbristow.com/articles/swingin-with-preston-love/

Coddington, Mark, “Grand Island’s historical hotels,” Grand Island Independent, Feb. 28, 2017, https://www.theindependent.com/news/grand-island-s-historical-hotels/article_2a32587f-fff0-5bda-9c66-11b49c134b09.html

Fourteenth Census of the United States: State Compendium, Nebraska, Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1925), 17. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1920/state-compendium/06229686v26-31.pdf

“The Hotel Yancey,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form. US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Nov. 14, 1984. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/84000504_text

McKee, Jim, “Yancey Hotels live on but not as hotels,” Lincoln Journal Star, Aug. 27, 2016. https://journalstar.com/news/state-and-regional/nebraska/jim-mckee-yancey-hotels-live-on-but-not-as-hotels/article_f8376f60-5ae4-5d7c-b695-ec18479a63ac.html

The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1940. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/dc858e50-83d3-0132-2266-58d385a7b928/book#page/23/mode/2up