By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

During the Indian Reform movement that began in the 1860s, reformers opened boarding schools to assimilate Indigenous youth to White, English-speaking culture. The US government came to believe that encouraging formal schooling and “civilization” would help resolve the “Indian problem.”

Supporters of assimilation saw themselves as humanitarians and defenders of Native Americans; opponents sometimes derided the reformers as “Indian lovers.”

“Today, however, assimilation is viewed as a cultural genocide,” writes C. P. Weaver in the Spring 2022 issue of the Nebraska History Magazine.

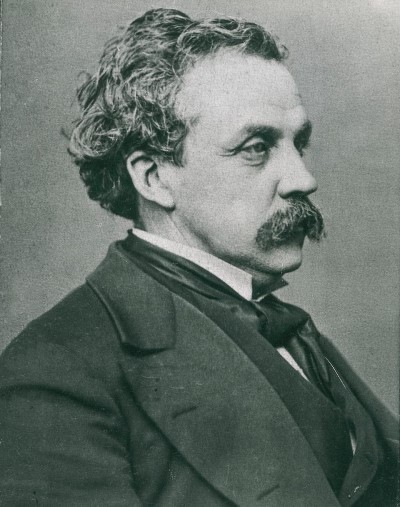

Samuel F. Tappan, an “Indian lover” and humanitarian, advocated for Indian rights and worked with the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Because of his reform efforts and political connections, in 1883 he was appointed superintendent of the new Genoa Indian Industrial School, the first Indian boarding school in Nebraska. (History Nebraska has other resources about the school’s history and troubled legacy here.)

Despite his work as an advocate, Tappan had no prior experience managing a school. As training, he spent two days at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania to “familiarize [himself] with the details of the management and the methods of governing and instructing pupils.”

Tappan arrived to Genoa in November 1883 and began what would be a disastrous first year.

The school opened in February 1884. Financial appropriations were extended through the summer, but money was tight by winter. There weren’t enough workers, supplies, or finances to support the school’s needs. The building needed repairs, the cattle from out-of-state were struggling to acclimate, and Tappan couldn’t afford to fence the pasture. There were also food supply shortages and issues with the delivery of fuel and medical, cleaning, and school supplies. Financial support from the government fluctuated for most of Tappan’s time as superintendent.

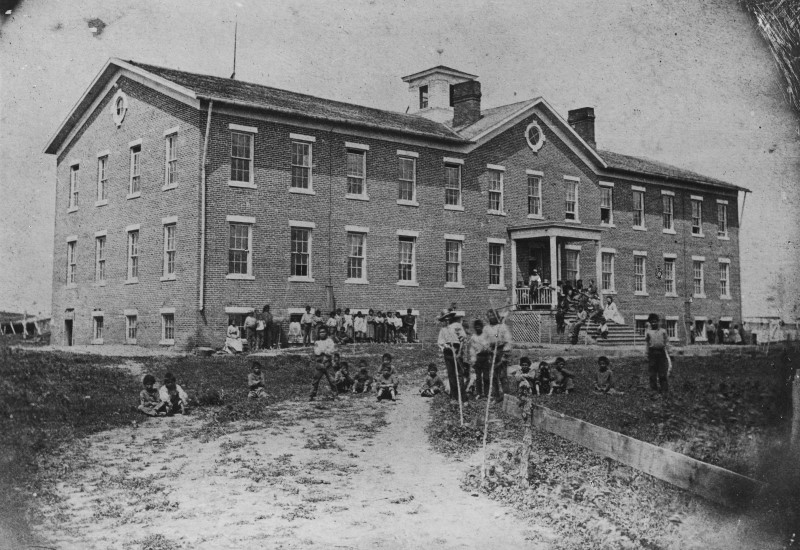

The Genoa campus had only one school buildling when Tappan arrived in 1883. Shown here in 1872, the building had been used as a school before the tribe’s removal to Indian Territory. RG2710-0-12

Meanwhile, conflicts with parents arose.

After rumors circulated about the school’s operations, some parents came to reclaim their children, a situation that Tappan likened to kidnapping. “One report told of fifteen Indians with several wagons, lurking north of the school in the hills and ravines.”

Tappan hired two extra guards, but as a long-term solution he pitched the idea of allowing students to visit home. This led to the concern of runaways.

In July of 1885, Tappan wrote to his supervisor about another alarming matter, warning that if it wasn’t addressed immediately, “the school [would] suffer.” Tappan said that several female students were bathing in a creek near a railroad bridge when a group of train workers stopped to taunt them. They “grossly insult[ed]” them with an “attempt to commit rape.” The men were arrested in August but were released when the court decided it was wrong to charge “white men upon evidence of Indians.”

Girls at the Genoa Industrial Indian School, 1884-85.” Author’s collection, photograph restored by Steve Rosenthal.

As a political appointee, Tappan’s job ended with a change of presidential administrations. He was relieved of his position in 1885.

In his final report, Tappan complained of bad conditions in Indian camps and reservations, and warned that Native girls were sometimes kidnapped from reservations and forced into prostitution. “He felt that the ‘only safety for the rising generation’ lay in the industrial boarding schools that were removed, located ‘among our own people.’”

Weaver writes, “However wrong or misguided we may find Tappan’s assimilationist role today, one cannot deny the weight behind his last entry that spoke to the heart of his reformist Indian agenda: ‘The only remedy is in the extension by Congressional legislation of the civil law over the entire Indian country and its rigid enforcement…”

(Posted 5/10/2022)

The long struggle for Native American legal rights is another story, but you can read about two landmark Nebraska cases here: Ponca Chief Standing Bear, who won an 1879 case recognizing him as a person under the law; and John Elk, who in 1884 was denied the right to vote by the US Supreme Court.

The entire article, “Samuel F. Tappan: First Superintendent of Genoa Indian Industrial School,” can be found in the Spring 2022 edition of the Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues per year.