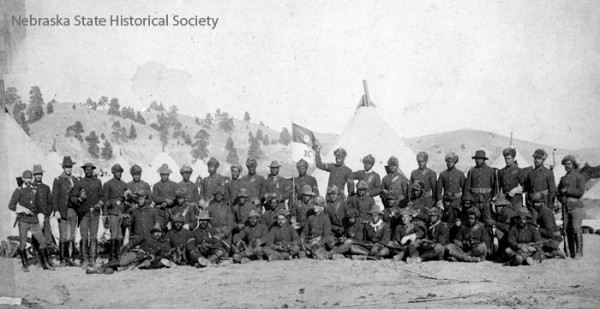

More than five thousand U.S. Army officers and soldiers were mobilized in the weeks leading up to the Wounded Knee Massacre. The troops – sent to subdue “hostile” Indians on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations – totaled nearly a quarter of the U.S. Army’s fighting strength. In the Spring 2014 issue of Nebraska History, historian Jerome Greene explains this drastic escalation of military tension step-by-step.

In the late 1880s, the future looked bleak for the Lakota Sioux. Confined to reservations, plagued by drought, disease, and low rations, many Lakotas turned to the Ghost Dance movement as a way to deal with their circumstances. The Ghost Dance was a religion that mixed Christianity and Native beliefs, teaching that following the dances correctly would bring salvation for the Native people and culture.

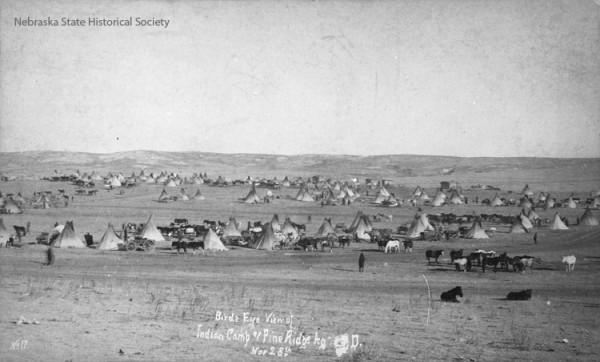

Government officials feared that the dances indicated an uprising. Agent Daniel Royer at the Pine Ridge Reservation sent a telegraph asking for military protection, saying: “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy. Nothing short of one thousand soldiers will settle this dancing.” White citizens around the reservations began requesting military protection as well. On November 13, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison ordered that a “body of troops sufficiently large to be impressive” be sent to the reservations.

Maj. Gen. Nelson A. Miles warned that Congress needed to address the Indians grievances directly, saying that “[the people] have been starved into fighting, and they will prefer to die fighting rather than to starve peaceably. Nevertheless, Miles followed his directions to send troops to the reservations. Troops were dispatched from Forts Omaha, Niobrara, and Robinson.

The press circulated sensationalized reports of battles, and more white settlers felt in serious danger. As hundreds of troops arrived on the reservation, the Indians began to feel in serious danger as well. A group of more than six hundred Indians on the Rosebud reservation began to flee towards Pine Ridge. Discovering soldiers there as well, they went north, killing cattle and wrecking cabins along the way.

Near the junction of Wounded Knee Creek and White River, the Indians resumed dancing, leading one Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke to report that “they are very defiant.” Within days, more troops were sent from Wyoming, Fort Omaha and Fort Sidney in Nebraska, and Fort Riley in Kansas, including an artillery unit. In December, nine troops of cavalry arrived. Later that month, hundreds of troops from Wyoming, Utah, Montana, and even California came to bolster forts and posts for miles around the reservations.

One Indian chief, Little Wound, was enraged by the soldiers’ presence. “Our dance is a religious one, and we are going to dance until spring…troops or no troops.”

Rumors and gossip spread fast while factual information hardly spread at all. Reporters predicted that the U.S. troops would advance to disarm the Ghost Dancers. Later, press representatives circulated a rumor that the Rosebud Indians were coming to kill Brooke.

More troops came. Tensions rose. And in the weeks leading up to Wounded Knee, the conflict had created the largest U.S. military mobilization between the Civil War and the Spanish-American war. All this conflict came to a head on December 29, 1890, when the Seventh Cavalry caught up to an escaping group of a Lakota. In the struggle to disarm them, a gun went off and the cavalry opened fire on men, women, and children. By the end of the massacre, more than 250 Lakota and 25 soldiers were dead.

Greene’s article is a part of a special issue of Nebraska History, “After the Indian Wars: People, Places, and Episodes,” which presents six papers from the Ninth Fort Robinson History Conference. Greene’s contribution is adapted from his book American Carnage: Wounded Knee 1890, published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

To learn more about the Wounded Knee Massacre, check out Eyewitness at Wounded Knee.

– Joy Carey, Editorial Assistant, Publications