In a blog posted on September 29, 2015, we introduced a brief history and purpose of the Nebraska Highway Archeology Program (NHAP) – a cooperative venture by the Nebraska Department of Roads (NDOR) and the Nebraska State Historical Society in place since

Highway Archeologist Amy Koch using a metal detector to find artifacts along the Sidney to Deadwood Trail in Dawes County.

Highway Archeologist Amy Koch using a metal detector to find artifacts along the Sidney to Deadwood Trail in Dawes County.

1959. The comments below address how we find and evaluate archeological sites in the path of highway construction. When the NDOR programs a highway construction project, it notifies the NHAP office and crews are dispatched to locate all the archeological sites, buildings and bridges that could be affected by construction. This survey normally occurs several years before construction and is a component of comprehensive environmental planning that includes work by specialists in buried hazardous materials, water quality, wetlands, noise and air quality, paleontology, and endangered plants and animals. Most important archeological sites will be within a reasonable distance from surface water sources since pre-modern people did not have water lines, wells, or irrigation. Research has also shown that certain topographic landforms are more likely to result in the long term preservation of archeological sites. With this information in mind, archeologists complete a surface survey of the construction areas and many sites are discovered simply on the basis of scatters of stone tools, animal bone, and pottery brought to the surface by plowing or erosion.

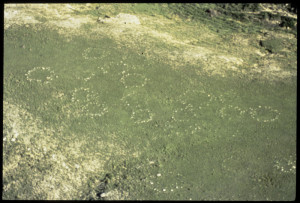

These dark circles are the tops of 800 year old refuse pits filled with broken pots, stone tools, and charred plant and animal food remains. There were discovered during road construction along a Sand Hills lake shore following removal of topsoil with a large scraper.

These dark circles are the tops of 800 year old refuse pits filled with broken pots, stone tools, and charred plant and animal food remains. There were discovered during road construction along a Sand Hills lake shore following removal of topsoil with a large scraper.

Vegetation-free stream banks and road cuts are also closely examined for evidence of debris left by people in the past. During the surface survey, crews will also look for mounds, depressions and linear swales that could mark the locations of Native American lodge sites, burials or old wagon trails. In addition to surface survey, a series of other discovery tools can be used in finding buried archeological sites. They include techniques such as aerial photography, mechanical topsoil removal, geophysical prospecting, deep backhoe trenching, and examination of archival documents such as maps and artwork.

Low level aerial photograph showing the location of ‘tipi rings’ in Kimball County near Interstate 80. These rings are comprised of stones collected from nearby buttes and each ring is about 10-20 feet in diameter. Indians would often use stones to anchor the edges of tipis – particularly before the introduction of iron pegs or in areas with limited timber resources.

Low level aerial photograph showing the location of ‘tipi rings’ in Kimball County near Interstate 80. These rings are comprised of stones collected from nearby buttes and each ring is about 10-20 feet in diameter. Indians would often use stones to anchor the edges of tipis – particularly before the introduction of iron pegs or in areas with limited timber resources.

Finding archeological sites and historic buildings and bridges that might be impacted by road construction is the first step in a longer process. Once sites are

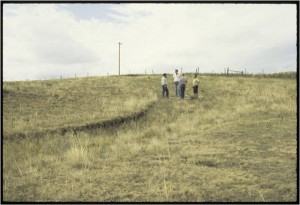

The curving depression is a segment of the 1876-1887 Sidney to Deadwood Trail in Cheyenne County.

The curving depression is a segment of the 1876-1887 Sidney to Deadwood Trail in Cheyenne County.

identified, NDOR, NHAP, Native American tribes, and other interested parties work together to determine if they are “Historic Properties.” Historic Properties are those which are on or are considered eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (see, http://www.nps.gov/nr/). These are sites that are exceptional in both their preservation and historical or archeological significance. To be National Register eligible, buildings and bridges must be in their original state and be directly associated with important events or people or be exceptional examples of a particular style. Over 90 percent of archeological sites or buildings discovered simply do not measure up to the standards of the National Register. Either they have been badly damaged by erosion, agriculture or previous construction or they do not contain data with which to address important research questions productively. In the case of buildings, many have been altered through remodeling and have lost their historic architectural integrity. Sites that are not of National Register caliber, are recorded and mapped but not further investigated before construction. If an historic property is in the path of road construction, NDOR designers will make every attempt to avoid the site or otherwise minimize the impacts. If avoidance is not possible, then archeological excavation will recover important data and make it available to the public and future generations of archeologists. A detailed recording project is initiated in the case of historic buildings and bridges that involves high quality photographs and drawings.

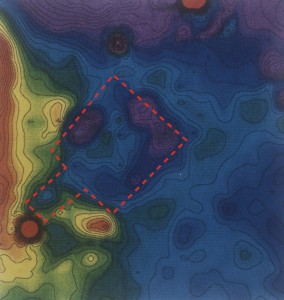

A proton magnetometer survey in an 800- year old Native American village in Sarpy County reveals the outline of the buried ruins of an earthlodge with an extended entryway (red dashed line). The dark purple areas within the lodge proved to be deep storage/refuse chambers filled with artifacts and other debris.

A proton magnetometer survey in an 800- year old Native American village in Sarpy County reveals the outline of the buried ruins of an earthlodge with an extended entryway (red dashed line). The dark purple areas within the lodge proved to be deep storage/refuse chambers filled with artifacts and other debris.

The next blog on the NDOR/NHAP partnership will focus on some of the excavation and recording projects. Stay tuned! by Rob Bozell, Highway Archeology Program Manager