The presidential campaign of 1896 was one of the most impassioned in US history. Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan, age 36, was revered as a godly hero and denounced as a dangerous radical. At issue were matters of silver and gold.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

This campaign pin from the Nebraska History Museum requires some explaining today, but its meaning was clear to 1896 voters. Pictured at left is 36-year-old William Jennings Bryan of Lincoln, the Democratic nominee for president. The numbers at right, 16/1, represent the ratio of silver to gold coinage desired by Bryan’s supporters.

What a boring issue, right? No wonder Bryan lost!

But the campaign of 1896 was one of the most impassioned in US history. Bryan was both revered as a godly hero and denounced as a dangerous radical. The country was still reeling from a severe economic depression, and many farmers felt that banking interests had rigged the economy against them. Opponents accused Bryan of being practically a socialist and warned that he would wreck the economy instead of saving it.

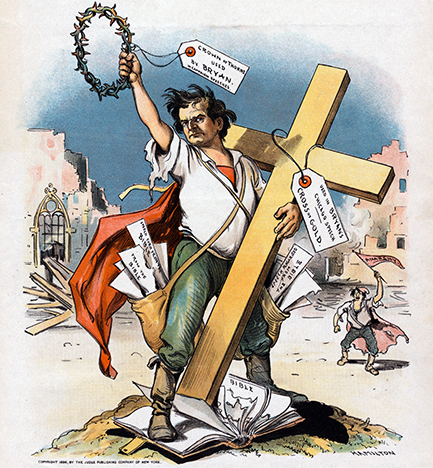

Image: A cartoonist from Judge magazine lampooned Bryan for using religious imagery to promote partisan political views.

When’s the last time you got into an argument about federal monetary policy? It happened a lot in 1896. At the center of the fight was “free silver” versus the gold standard.

This takes some explaining. In some important ways, money was different then. Today we have a federal reserve banking system (“the Fed”) that controls the supply of money—not a simple task when the economy keeps changing. Too much money in circulation results in inflation; too little results in deflation and tight credit. Most of us don’t really understand exactly what the Fed does, but we recognize that it plays an important role in stabilizing the boom-and-bust cycles of the economy.

But in 1896 there was no Fed. The value of the dollar was pegged to the value of gold. Over the years the economy had grown a lot faster than the amount of gold in circulation.

That meant deflation. Prices fell, wages fell, and the value of a dollar grew. This was good if you already had a lot of money, or if people owed you money. But if you carried debt, as most farmers did, it meant you now had to pay back your loans in dollars that were worth more than what you borrowed. Bryan called this a “Cross of Gold” in his most famous speech.

Bryan and his supporters believed the solution was “free silver.” This didn’t mean literally giving away silver. It meant that the government would go back to minting silver coins, which it had stopped doing. The idea behind silver coinage was that it would expand the money supply and create enough inflation to ease debts and make credit easier to obtain.

Opponents wanted to keep the US on the gold standard. Supporters of Republican nominee William McKinley argued that gold made for a stable currency, which was good for business, and thus good for urban wage workers. McKinley supporters often wore yellow neckties or “gold bug” pins shaped like this one. (A savvy manufacturer apparently sold them to both parties.) The stinger, only barely visible here, was a lever that moved the wings.

The issue was argued in numerous books, pamphlets, speeches, and fistfights. The 1890s saw major droughts, economic depression, massive unemployment, violent labor strikes, lynchings, and widespread unrest. During such times, the silver issue became a focal point for many Americans’ hopes and fears.

McKinley won the election and kept the nation on the gold standard. Why did he win? Opinions vary, but historians often emphasize two factors. One is that McKinley raked in huge donations from corporations and wealthy individuals, allowing his campaign to massively outspend Bryan. The other is that Bryan and the free silver platform appealed mainly to rural Americans and not so much to urban workers.

The “Free Silver” platform was dead, but Bryan himself was nominated by the Democratic Party twice more, losing to McKinley again in 1900 and to William Howard Taft in 1908. However, Bryan remained a powerful figure among Democrats for years, and served at US Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson.