Although the hobby of collecting political memorabilia is probably as old as politics, the political campaign button first became important in the presidential election of 1896. This contest, in which Republican William McKinley defeated Democrat William Jennings Bryan, spawned a wide variety of colorful buttons, made by placing a thin layer of celluloid over a paper image on a metal disk with a small metal pin attached on the reverse.

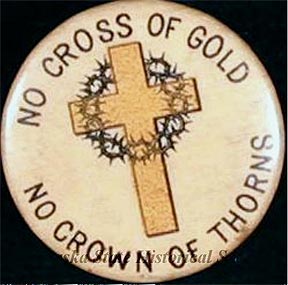

The inscription on this campaign button refers to William Jennings Bryan’s famed 1896 speech. NSHS 11571-7

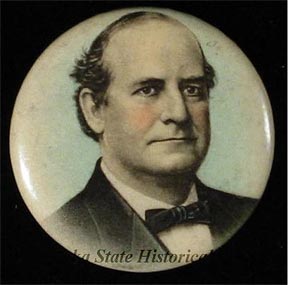

A photo portrait of Bryan appears on this campaign button. NSHS 4123-2-(4)

In 1896 hundreds of different celluloid buttons were issued for that year’s political campaigns, some by politicians and some by private companies that advertised their products on buttons boosting one candidate or another. “‘No presidential possibility without a campaign button,’ is what the boomers of the eastern candidates are crying,” said the Omaha Daily Bee on March 22, 1896. “As if there were anything in the law or the constitution that made the distribution of a campaign button one of the prerequisite qualifications to the presidency.” As campaign buttons flooded onto the market, enthusiasts soon began rounding up samples of the most colorful. By the time of the November elections in 1896 political buttons were being avidly collected. The Bee asked in November: “Have you the button habit? If not you are lucky. It is the latest craze and is raging with great virulence just now. Nearly every day sees its ravages increase, and until after the election it will prevail.”

Some of the most memorable campaign buttons from 1896 in the collections of the Nebraska State Historical Society feature Democratic candidate Bryan. In addition to photo portraits of Bryan or of Bryan and his running mate, Arthur Sewall, there are buttons proclaiming “No Cross of Gold,” referring to Bryan’s famed 1896 speech which won him the Democratic presidential nomination. Political buttons were soon augmented by buttons with slang expressions or humorous slogans upon them. The Bee said, “‘Rubber Neck’ is a favorite button, and among other inscriptions are: ‘Just Tell Them That You Saw Me,’ ‘I Am for Easy Money,’ ‘If You Love Me, Grin,’ and ‘What Will You Have?’ These buttons are the especial pride of callow young men and the newspapers last week recorded the breaking of a wedding engagement by a young woman who found on her inamorata’s coat two buttons reading: ‘Let’s Have Another Round’ and ‘Don’t Care If I Do.'” So pervasive had the button craze become in 1896 that “[l]ittle girls have started collecting clubs, and some of them wear the entire collection on their clothing, arranging the buttons in double rows around their hats and on their cloaks like trimming. Cigarette firms give away the buttons bearing their ‘ad’ in small type under the inscription, and dealers are besieged by the little ones for buttons. When the campaign of 1896 passes into history at least the buttons will long remain as reminders of its exciting days.”