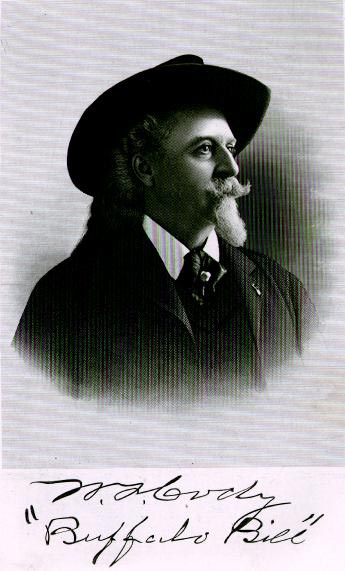

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and his Wild West were major attractions at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. However, a few members of the Wild West did not approve of some Eastern art depicting the West. The Young Men’s Journal (Omaha), on June 2, 1893, reprinted a story from a Chicago newspaper indicating that one particular statue was deemed objectionable.

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and his Wild West were major attractions at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. However, a few members of the Wild West did not approve of some Eastern art depicting the West. The Young Men’s Journal (Omaha), on June 2, 1893, reprinted a story from a Chicago newspaper indicating that one particular statue was deemed objectionable.

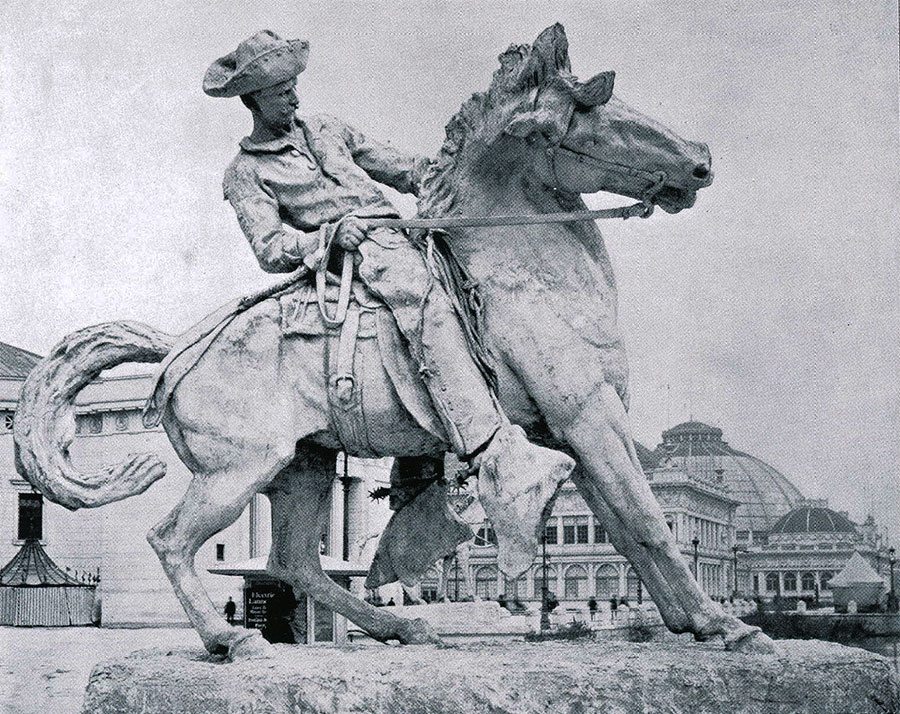

The fairgrounds of more than six hundred acres included canals and a lagoon as well as exhibit buildings with facades made of plaster, cement, and jute fiber, which were painted white. The Journal said: “Only for the interference of ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody last evening [Alexander P.] Proctor’s statue of a ‘typical cowboy,’ which was recently erected near the north end of the transportation building, would have been dumped into the lagoon.

“Yesterday morning some of the boys from the show went over to see the fair, and one of the first things they struck after entering the grounds, was the equestrian statue. They gathered around it and were having all kinds of fun in criticizing the rider’s seat in the saddle and the ‘help!’ ‘help!’ way in which the alleged cowboy was hanging onto the reins, when a Columbian guard explained to them that it was not intended to illustrate a tenderfoot taking his first ride on a farm horse, but was supposed to be a typical cowboy, one of the very best of his class, executing a daring feat of horsemanship.

“There was a hurried consultation among the boys, . . . Efforts to dispose of the presence of the guards aroused their curiosity, and they gathered closer around the group of ‘broncho busters’ instead of moving away, and finally were taken into confidence in the matter. The cowboys proposed to resent the insult that the sculptor had offered to their fraternity by throwing the plaster ‘cow-puncher’ and the Clydesdale draft horse upon which he is mounted into the lagoon, and they wanted the guard[s] to look the other way while they did it.

“Whether they were restrained by the fear that they might lose their jobs or whether they did not agree with the cowboys as to the merits of the equestrian statue matters not, the guard[s] would not go, and the attempt to avenge the real or fancied injustice that had been done to them was apparently abandoned, and the men returned to take their places in the afternoon performance. They had not, however, given up the idea of having some fun with the statue, and during the afternoon performance a plan was made up for a delegation of men who have ridden the range from the Panhandle to the Big Horn to go over to the grounds as soon as it was dark and give the plaster figure a swim in the lagoon. One of the men accidentally dropped a hint of their plan to Major Burke [front man and manager/press agent for the Wild West], and he at once took measures to prevent the cowboys from making their art criticisms in such a radical way.

“After the show Colonel Cody called the cowboys together and told them that while it was considered fashionable and correct to call things by their proper names on the other side of the Missouri, on this side a man had to be quite a graceful liar to be in good standing in society. He told the boys that he had not seen the objectionable statue and did not know whether it was good or bad, but that they must not think of throwing it in the lagoon because it did not meet with their approval.

“At first the boys were inclined to demur; they had planned revenge, and it was hard for them to relinquish the idea. The statue offended them-it was a travesty and should be removed. Colonel Cody, however, quietly informed them that he would personally resent the act if the statue were molested. That settled it. Mr. Proctor’s figure is not in the lagoon.”

Proctor’s “Cowboy” at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893.

Photographic illustration from “The Dream City, A Portfolio of Photographic Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition with an introduction by Halsey C. Ives”

(St. Louis: N.D. Thompson Co., 1893 – 94). Photo: Centerofthewest.org