Earlier this year, the Ford Conservation Center took on a project to conserve an interesting piece of the History Nebraska collection. The item was unique in its own right but precious for representing a family’s history with ties to Lincoln, Nebraska, homesteading communities, and the early civil rights movement.

A tiny, well-worn daily prayer book came to History Nebraska as part of a collection from the Vanderzee-McWilliams family. The matriarch, Ruth Cox, was born into slavery around 1818. She escaped in 1840 and was welcomed into the home of Fredrick Douglass in Massachusetts. At the time, they believed that they might be siblings – Ruth bore a resemblance to Douglass’ sisters, and she had a brother who shared the name Douglass had had under slavery. Today, it is believed that they may have been cousins.

Photo of Ruth Cox Adams, who is buried at Lincoln’s Wyuka Cemetery. Source: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/63313957/ruth-adams

Ruth Cox was a tutor in the Douglass home until she married Perry Adams in 1847. They had a daughter, Matilda Ann, in 1849 and moved to Haiti for some years after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Matilda Ann married William Henry Vanderzee, and the two of them moved to Holt County, Nebraska, to homestead. Her mother, by now a widow, accompanied them. Later, due to William’s failing eyesight (he eventually became blind), the family moved to Lincoln, where they and their descendants would become influential members of the city’s Black community.

One of Matilda and William’s daughters, Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee, became an accomplished concert pianist and married Ralph McWilliams. The McWilliams family and their descendants stayed in Nebraska and were instrumental in constructing Lincoln’s Third Christian Church (AME) on 23rd Street between O and P. Three generations of men in the family served as Lincoln preachers – first at Third Christian, then at Christ Temple Mission, which became the city’s first integrated congregation under Rev. Trago McWilliams, Jr.

Another daughter, Anna Rebecca Vanderzee, was born in about 1880. She graduated from Lincoln High School, and in 1902, she traveled to Washington to participate in a program that sought to reduce the early education gap between Black and white students. As a result, young Black women received training to become kindergarten teachers and were placed in communities with few teachers, particularly in the south. The small daily prayer book is inscribed as “Anna Vanderzee, Omaha.”

Anna Vanderzee (1902), from an unidentified newspaper article detailing her participation in the program to train as a kindergarten teacher. Source: History Nebraska.

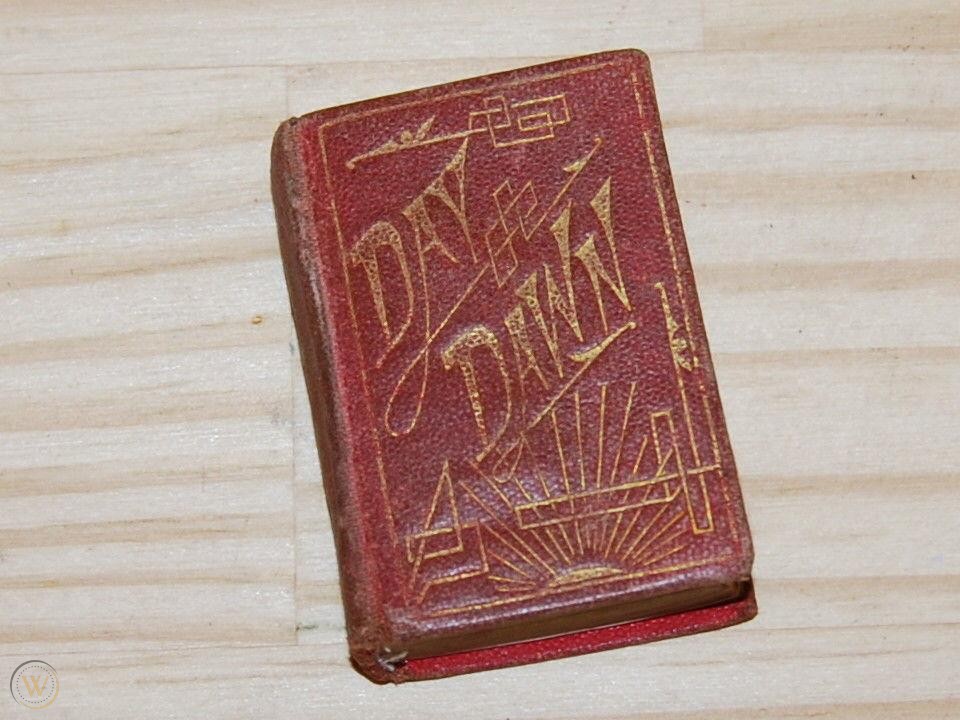

When it came to the Ford Center, the book was obviously well-used. In Image 1, you can see a partially legible imprint on the front cover with the words “Day-Dawn.” Unfortunately, it wasn’t possible to date the book because the first seven pages (including the title page) were missing entirely. However, research revealed that the book was published by the American Tract Society, NY, likely sometime in the mid-late 1800s.

Vanderzee Prayer Book Conservation Image (Image 1)

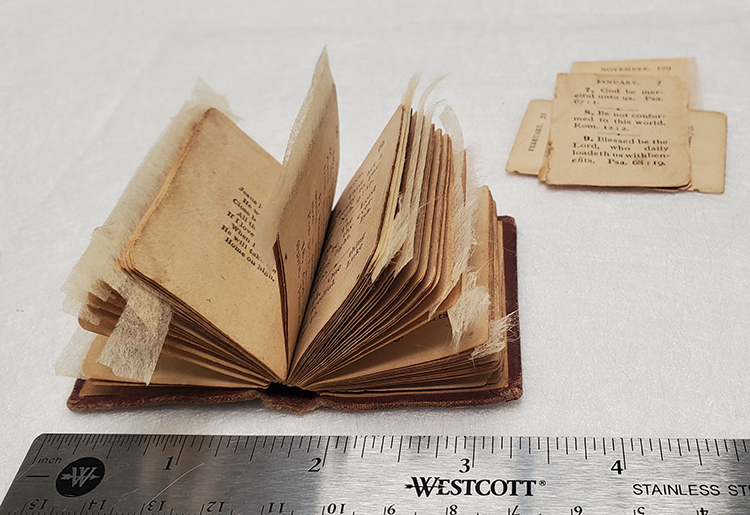

Image 2. Source: Image source: https://thumbs.worthpoint.com/zoom/images1/1/0518/05/day-dawn-american-tract-society_1_32158a164e0ec223b6f604db93580aaa.jpg

Image 2 provides an idea of what the Vanderzee book would have looked like before the gold inlay was worn off. Because the book in the History Nebraska collection is being preserved more for its historical significance than for display or collection purposes, it was decided that no aesthetic compensation, like inpainting the gold text on the cover, would be part of the Vanderzee book’s treatment.

In addition to the missing pages, others were loose, and still, others had been torn or heavily creased. The missing pages had created voids in the binding that weakened the whole and could eventually lead to additional loss.

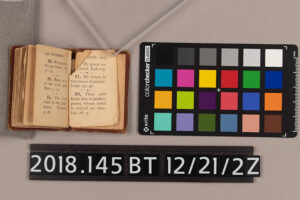

The first stage of conservation addressed the book’s individual pages. Torn or creased pages were strengthened using lightweight Japanese paper, while incomplete pages were made whole using conservation papers and adhesive. Making all pages uniform in size and shape helps to prevent future snags and tears.

In Image 3, you can see the book after strips of Japanese paper were added to weak or damaged areas. These repairs were then trimmed off and made flush with the original edges. (Note the ruler at the bottom of these images – this book was TINY!)

Image 3. Vanderzee Prayer Book with Ruler to show size of book.

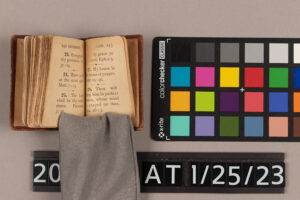

Next, to stabilize the book and prevent further loss, all the pages (the “text block”) were entirely removed from the case. Next, the text block was split into sections and resewn by hand using a needle and thread. Image 4 provides a good view of the book’s sections and the new stitching. Typically, a book press would hold the book in place while treatment is finished, but this book was so small that a binder clip was a more appropriate size.

Image 4. Vanderzee Prayer Book

Image 5. Vanderzee Prayer Book

Finally, a heavy-weight paper hinge was adhered over the spine of the text block (Image 5) to secure it into the case.

Image 6.

Image 7

Images 6 and 7 show a before and after view of one of the book’s more heavily damaged pages. Missing material was reconstructed to stabilize what remained, and the page was sewn back into the binding.

After conservation, the book is structurally stable and can be safely handled for research and exhibition.

Sources:

Ulrich, Linda. “Faith, pride have marked blacks’ history in Lincoln.” Lincoln Journal Star, February 25, 1979. History Nebraska.

“Kindergartner for Work Among Southern Negroes.” Unidentified publication, June 15, 1902. History Nebraska.