By David L. Bristow, Editor, Nebraska History

(Originally posted March 29, 2019)

J. Sterling Morton’s Nebraska Hall of Fame bust at the State Capitol.

On one level this is an easy question. Yes. Blatantly. In a loud and unambiguous way. Though not as famous as he once was, Morton is still celebrated as the founder of Arbor Day. He is an inductee of the Nebraska Hall of Fame, and is the central figure of Arbor Lodge State Historical Park. Until recently his statue stood in the US Capitol.

Morton was an ardent defender of slavery before the Civil War. He opposed the Emancipation Proclamation during the war, and for the rest of his life maintained publicly that black people were an inferior race not entitled to equal rights.

Consider this:

“I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races… I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office… there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will for ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality….”

There you go, right?

There’s just one thing. That wasn’t Morton. That was Abraham Lincoln. [1]

Here is one of the difficulties with making value judgments about the past. History is full of bigotries and systematic cruelties that people just accepted as the natural order. Hold a hero up to the light, and you’re almost certain to find deeply-held beliefs that make you cringe.

So one way to respond to Morton or Lincoln is to say it’s not fair to judge them by today’s standards.

Consider the Lincoln quote. Which is less excusable: Lincoln saying this in 1858, or someone saying it in 2019? The question is easy because we recognize that we are all, to some extent, products of our own time and culture.

But of course we do judge people of past in many ways. Every street, building, or town bearing someone’s name is a form of judgment. Every statue, historical site, book, or blog post is a form of judgment. And when we celebrate a historical figure’s positive accomplishments without examining the negative ones, that too is a form of judgment. Even without stating opinions, our selections reveal our values and priorities.

So is there way to judge a man like Morton fairly, and maybe learn something useful for our own day?

I think there is. We can ask: In what ways did this person help create a more just and humane world, and in what ways did they hold us back?

In other words, we can recognize that people have started from different places culturally and intellectually, and we can look at what they did with their opportunities. We may differ from one another on some points of what it means to be just and humane, but this at least provides a basis for conversation.

The point of such a conversation shouldn’t be simply to tear down somebody else’s heroes or to defend one’s own, but rather to learn from our collective experience.

So let’s try it. How does this apply to J. Sterling Morton? His record regarding Arbor Day is pretty well known. In the rest of this post I’m going to look at his record on race.

Slavery in Nebraska Territory

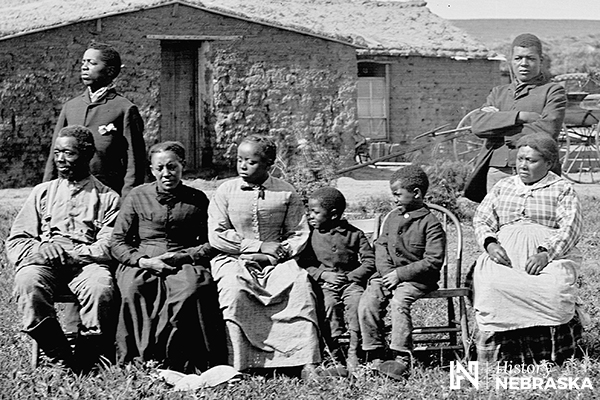

Earliest known of photo of African Americans in Nebraska, taken in Brownville in 1864, three years after the territory banned slavery. History Nebraska RG3190-283.

Julius Sterling Morton was born in Adams, New York, in 1832. He grew up in Michigan, and in 1855 settled in Nebraska City, where he became editor of the Nebraska City News. For the rest of his life he was a power in the Nebraska Democratic Party, eventually serving as U.S. Secretary of Agriculture. (Read more in this biographical sketch.)

Slavery was legal in Nebraska until the territorial legislature banned it 1861. Nebraska never had many enslaved people, but the controversy reflected the intensity of the ongoing national debate.

Morton fought to keep slavery legal in Nebraska. In 1858 he complained that the “Black Republicans” in the territorial legislature were “reaching out from day to day after the n—-r question.” [2] (Morton didn’t use dashes for that word, but I will throughout.)

Morton and the Civil War

Colors of the 1st Nebraska Cavalry, with the names of their major battles. Out of barely 9,000 men of military age, Nebraska Territory sent more than 3,000 soldiers into the Union Army. History Nebraska 7135-389-(1)

Then came the secession crisis. In 1860-61, eleven Southern states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America.

Everyone knew why. The issue was slavery. President-elect Abraham Lincoln had pledged not to interfere with slavery where it existed, but he opposed its expansion into new territories. Southerners believed they needed new slave states to protect their “peculiar institution.”

In official declarations and speeches by elected officials, Southern states made it absolutely clear that they were leaving the US for the defense and expansion of slavery.

In his inaugural address, for example, Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens said that the new nation’s

“cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” [3]

Morton wanted to preserve the Union by protecting slavery. He supported the “Crittenden Compromise,” a proposal to lure Southern states back into the Union. The idea was to amend the US Constitution to guarantee the permanent existence and expansion of slavery. Both sides rejected the plan, and Morton’s enemies began to claim that his “sympathy with the southern traitors is known and read of all men.” [4]

That wasn’t an idle accusation. As the Civil War began, Morton’s own father had doubts about his son’s loyalty, writing in an 1861 letter that “I hope you will be a loyal citizen supporting the Government right or wrong against the southern traitors and treason.” [5]

Morton insisted that Republicans had provoked the war, and allied himself with anti-war Democrats. He was a good friend of US Rep. Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, the leader of the “Copperhead” faction who was arrested and exiled to the Confederacy. In 1863 Morton even dismayed some of his Democratic friends by publicly expressing partial support for Vallandigham’s proposed Northwestern Confederacy, in which Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois would secede and ally themselves with the South. [6]

Morton attacked President Lincoln in print throughout the war, and considered the Emancipation Proclamation an act of despotism. Morton grew increasingly despondent at what he saw as Lincoln’s tyranny, writing to his mother in 1864: “To me the future of what was once the United States looks dark and fearful.”

Morton seriously considered leaving the United States. At various times he thought about moving to Canada, the Bahamas, Mexico, or Hawaii (not yet a US territory). [7] But he stayed.

Nebraska Statehood and the Freedmen’s Bureau

The Great Seal of the State of Nebraska. For many years this was a skylight window in the US Capitol. History Nebraska 7434-2

After the war, Morton wrote the part of the 1865 Nebraska Democratic platform which condemned Republican attempts to force Southern states to allow black men to vote. [8] The following year, as Nebraska considered adopting equal suffrage as part of its application for statehood, Morton argued in an editorial that Nebraska should only do so if forced by Congress:

“It will be more manly to accept negro suffrage by legal enforcement than to humiliate ourselves by its voluntary adoption as the price of admission to the Union… We take n—-r only when forced to it by Congress and therefore are for remaining at present a territory.” [9]

Congress did just as Morton feared in 1867, requiring Nebraska to grant black men the vote as a condition of statehood. [10]

Morton also publicly denounced the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency that provided temporary services to formerly enslaved people. In 1866 Morton called the bureau “an outrage upon the white population of the country… [expending] $20,000,000 per annum on the education, clothing and feeding of the n—–s, while nothing whatever is being done for whites who are equally poor.” [11]

Moses Speese family, Custer County, Nebraska, 1888. Speese and his wife, Susan, were born into slavery, and led a group of African American settlers to Nebraska in the 1870s. There they faced many forms of discrimination, but the men’s voting rights were secure. History Nebraska RG2608-1345

Later Years – the White Man’s Burden

Morton in 1889. History Nebraska RG1013-20-12

As the years passed, slavery began to seem less and less acceptable even to those who had formerly defended it. In the South, this changed view was expressed in the growing mythology of the “Lost Cause,” which claimed—against all evidence—that the war hadn’t been about slavery at all.

Morton was no Southerner, and in 1891 he gave a Northern interpretation of the war in a speech to the Nebraska State Historical Society (as History Nebraska was then known). Describing the slavery controversy, he said:

“But through the mists of sophistry and above the wrangle of debate was seen and heard at last a figure of justice demanding mercy and liberty for an oppressed race. And from the first establishment of civil government in Kansas and Nebraska until the sound of the last gun of the great civil war in 1865 there was no cessation in the intensely fierce combat for the natural rights of man.” [12]

Morton neglected to mention his own support for slavery during those years, but does this mean that his racial views had changed?

The best source of Morton’s public opinions in his final years is The Conservative, a weekly paper he published in Nebraska City from 1898 until his death in 1902.

(If it seems strange that a Democrat would publish a “conservative” paper, it wasn’t. Morton was a states’ rights, small-government, gold-standard Democrat opposed to progressives like William Jennings Bryan. Party platforms and defining issues have changed dramatically over the years, which is why it’s a bad idea to draw conclusions about present-day political parties based on what they stood for generations ago.)

In his editorials, Morton denounced lynchings of African Americans and protested the persecution of “peaceable reservation Indians in Minnesota.” He hated and feared mob violence, and called for a larger standing army to put down “riots, mobs, or other seditions.” [13]

But he also argued that “government by consent of the governed” did not apply to African Americans, and he endorsed the efforts of Southern states to disenfranchise black men. [14]

In 1899 Morton praised Rudyard Kipling’s latest poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” which framed imperialism as the duty of white nations to colonize non-white nations for their own good. But Morton warned against trying to absorb “savages and barbarians” into democratic governments, and said that Americans who sought to evangelize Cuba and the Philippines with civilization and Christianity “are morally and intellectually very near-sighted.” [15]

In 1900, Morton reprinted a paper from a Virginia medical conference that argued that African Americans had been better off morally and physically under slavery. As a “subordinate race,” the “negro will remain with us in the South, if he will but give up his aspirations to full citizenship and confide his education and government to the whites, who, in times past, have proved their love for him,” and accept his role as “the white man’s servant, ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water.’” [16]

Morton saw unbridgeable racial divisions among white people as well. In an 1898 editorial he praised Italian immigrants for their thriftiness and marveled at “the astonishing persistence” of Greeks and Jews, two “ancient races” that had not and could not assimilate with the mainstream population:

“[A] descendant of Abraham no more combines with the community in which he finds himself than a bullet with the snowbank into which it is dropped; he is always, first and foremost, a Hebrew.”

Even while expressing admiration for other white “races,” Morton nevertheless saw them as forever separate from his people. “We,” he said—addressing his readers, “are neither one nor the other of them, but Teutons, from time immemorial.” [17]

The Teutons were an ancient Germanic tribe, but Morton made it clear that he was using the term to include all of the vaguely Germanic Northern European peoples.

Morton was no longer the angry young man railing against Lincoln. His later writings and editorial choices reveal a man who was convinced of his own benevolence toward other races, looking down on them kindly from across an unbridgeable gap.

Conclusion: How should we judge Morton’s racial views?

A few key points:

First, Morton was a mainstream figure, expressing views held by thousands of Nebraskans and millions of Americans. To portray him as a singularly bad individual is to ignore the deep-rooted racism of American culture.

Nevertheless, he was an influential public man expressing public views, and remains an honored figure in Nebraska to this day. He is a fair target for criticism.

Morton’s views on race and slavery were a major part of his political identity, and therefore should be a major part of his historical legacy.

It’s fair to acknowledge that Morton didn’t represent the absolute worst mainstream views of his time. He held back from openly endorsing Southern secession, and later condemned lynching. The latter puts him ahead of the Omaha World-Herald and Omaha Daily Bee, both of which openly instigated the lynching of a black man in 1891. [18]

Nevertheless, Morton was consistently on the wrong side of racial issues, ignoring and belittling the voices of equality while amplifying the voices of bigotry and reaction. Abraham Lincoln, quoted earlier in this post, was wrong about a lot of things regarding race, but he and millions of other white Americans were significantly less wrong than Morton.

Even our state motto, “Equality Before the Law,” stands as a rebuke to Morton and his allies. Nebraska’s choice of this motto in 1867 came directly from the black voting rights controversy at the time of statehood. [19] “Equality Before the Law” is a principle that Morton opposed for his entire life.

To return to our big question: In what ways did this person help create a more just and humane world, and in what ways did they hold us back? This article deals with only one aspect of Morton’s career, but at least in terms of race it’s fair to say that he did little to create a more just and humane world, and did much to prevent its growth. If you remember him when you plant a tree on Arbor Day, remember this as well.

Morton statue at Arbor Lodge, his home in Nebraska City. History Nebraska RG2352-4-23

Reference Notes

[1] The quote is from the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. See, “Fourth Debate: Charleston, Illinois,” Lincoln Home National Historic Site (National Park Service). https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/debate4.htm

2 James C. Olson, J. Sterling Morton (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1942), 93.

3 Full text of the “Cornerstone Speech” is posted at Wikisource: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cornerstone_Speech. See also, “The Declaration of Causes of Seceding States,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/declaration-causes-seceding-states.

4 Olson, J. Sterling Morton, 114.

5 Olson, J. Sterling Morton, 123.

6 Olson, J. Sterling Morton, 119, 122-23; James E. Potter, Standing Firmly by the Flag: Nebraska Territory and the Civil War, 1861-1867 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 191-92. Potter also writes about Morton’s controversies during the Civil War in, “Would J. Sterling Morton have sacrificed his grandmother for political gain?” History Nebraska Blog, April. 29, 2016. https://history.nebraska.gov/blog/flashback-friday-would-j-sterling-morton-have-sacrificed-his-grandmother-political-gain

7 Olson, J. Sterling Morton, 126, 130-31.

8 Olson, J. Sterling Morton, 135.

9 Potter, Standing Firmly by the Flag, 231-32.

10 See, “Nebraska Statehood Launched in Troubled Times,” https://history.nebraska.gov/blog/nebraska-statehood-launched-troubled-times

11 Olson, J. Sterling Morton, 146.

12 J. Sterling Morton, “Early Times and Pioneers,” Transactions and Reports of the Nebraska State Historical Society, Vol. 3 (1891), 101.

13 The Conservative, Oct. 20, 1898, Nov. 3, 1898. See also, Sept. 12, 1901.

14 The Conservative, Mar. 14, 1901, Feb. 22, 1900, Dec. 6, 1900.

15 The Conservative, Feb. 23, 1899, Oct. 20, 1898.

16 The Conservative, June 14, 1900.

17 The Conservative, Nov. 17, 1898.

18 See Omaha World-Herald and Omaha Daily Bee, Oct. 8, 1891; see also, David L. Bristow, A Dirty, Wicked Town: Tales of 19th Century Omaha (Caldwell, ID: Caxton Press, 2000), 227-237.

19 James E. Potter, “‘Equality Before the Law’: Thoughts on the Origin of Nebraska’s State Motto,” Nebraska History 91 (Fall/Winter 2010): 116-21. Archived as a PDF.